Part 1 – The Elopement

On a Sunday night in the summer of 1851, a young Amherst County doctor and the daughter of a wealthy neighbor slipped out of Lynchburg “with the purpose of marrying.” Within days, one man was dead, two were badly wounded, and Virginia newspapers were struggling to explain how an elopement could turn into what one called “another most painful tragedy.”[1]

Two “highly respectable” families

The local press took pains to reassure readers that this was not some back‑country brawl. The Lynchburg Daily Virginian stressed that the parties “all of whom resided in Amherst county, are highly respectable,” reminding readers that Capt. Richard G. Morriss “was once a member of the legislature from Gloucester County, and is a man of high standing, wealth and influence.”[2]

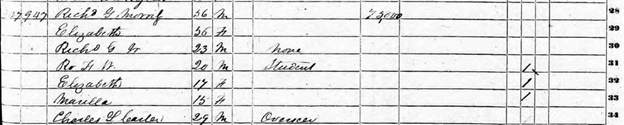

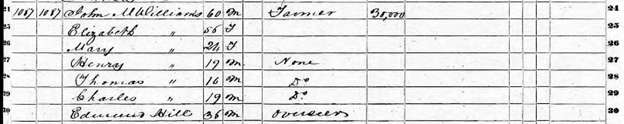

That description matches what we see in the 1850 census. Capt. Morriss’s real estate was valued at $75,000, with 79 enslaved people counted in his household.[3],[4] Nearby, the Williams patriarch, John M. Williams, held land worth about $30,000 and was recorded with twenty‑three slaves.[5],[6] His son, Lorenzo D. Williams, the young doctor at the center of this story, was off at Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia when the census taker came through.[7]

These were men used to being obeyed. They were also men whose sons carried pistols as routinely as pocketknives.

“We have barely space to announce…”

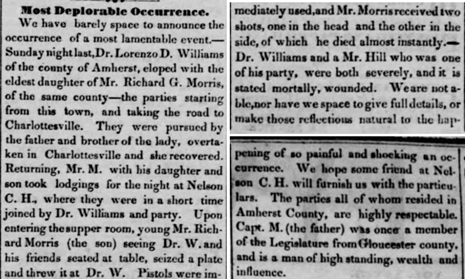

The first public notice of what happened appeared in the Daily Virginian under the headline “Most Deplorable Occurrence.” It opened with a confession: “We have barely space to announce the occurrence of a most lamentable event.”

In a single breathless sentence, the editor laid out the outline of the story:

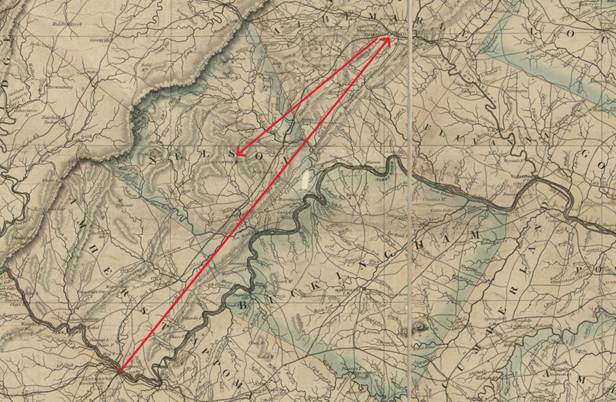

“Sunday night last (29 June 1851), Dr. Lorenzo D Williams of the county of Amherst, eloped with the eldest daughter of Mr. Richard G Morriss, of the same county – the party starting from this town, and taking the road to Charlottesville. They were pursued by the father and brother of the lady, overtaken in Charlottesville and she recovered.”

From there, the notice follows both parties to Nelson County Court House, where Capt. Morriss, his daughter, and his son took lodgings for the night and were “in a short time joined by Dr. Williams and party.”

What happened next takes only a few lines, but it is unforgettable:

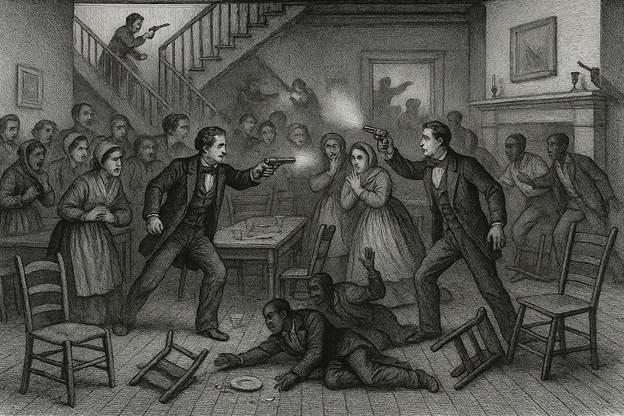

“Upon entering the supper room, young Mr. Richard Morriss (the son) seeing Dr. W and his friends seated at table, seized a plate and threw it at Dr. W. Pistols were immediately used, and Mr. Morriss received two shots, one in the head and the other in the side, of which he died almost instantly.”

The same paragraph notes that Dr. Williams and “a Mr. Hill” were “severely, and it is stated mortally, wounded.” Then the editor concedes: “We are not able, nor have we space to give full details, or make those reflections natural to the happening of so painful and shocking an occurrence. We hope some friend at Nelson C. H. will furnish us with the particulars.”[9]

That “friend” duly stepped forward.

“Another dreadful tragedy”

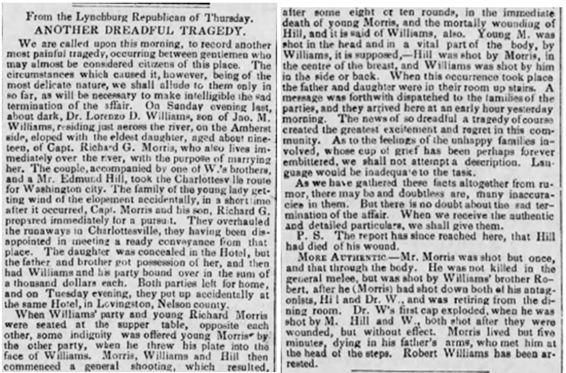

Within days, the Richmond Daily Times reprinted a far more detailed account from the Lynchburg Republican, under the headline “ANOTHER DREADFUL TRAGEDY.”[10] The tone is almost weary: “We are called upon this morning, to record another most painful tragedy, occurring between gentlemen who may almost be considered citizens of this place.”

This version gives us a clearer picture of the elopement itself. It notes that on Sunday evening, “about dark,” Dr. Williams, “residing just across the river [from Lynchburg], on the Amherst side, eloped with the eldest daughter, aged about 19, of Capt. Richard G Morriss, who also lives immediately over the river, with the purpose of marrying her.” The couple, accompanied “by one of W’s brothers and a Mr. Edmund Hill,” took “the Charlottesville route for Washington city.”

The Morriss family, we’re told, got wind of the elopement “accidentally,” but moved quickly: “Capt. Morriss and his son, Richard G prepared immediately for a pursuit. They overhauled the runaways in Charlottesville; they having been disappointed in meeting a ready conveyance from that place.” The daughter was “concealed in the Hotel,” but the father and brother “got possession of her, and then had Williams and his party bound over in the sum of $1000 each.”

So far, this is an intense but not unheard‑of nineteenth‑century story: a father dragging back an underage daughter, a young doctor forced to post bond and stand down, and everyone turning their carriages toward home.

“Some indignity was offered…”

It was the return journey that turned the story into tragedy. In the Republican’s account, both parties “put up accidentally at the same Hotel, in Lovingston, Nelson County.” The wording leaves room for fate to shoulder some of the blame.

There, in the supper room, the fragile truce collapsed:

“When Williams’ party and young Richard Morriss were seated at the supper table, opposite each other, some indignity was offered young Morriss by the other party, when he threw his plate into the face of Williams. Morriss, Williams and Hill then commenced a general shooting, which resulted, after some 8 or 10 rounds, in the immediate death of young Morriss, and the mortally wounding of Hill, and it is said of Williams, also.”

Notice how the verbs pile up: “some indignity… offered,” “threw his plate,” “commenced a general shooting.” The writer admits that he cannot say exactly who did what to whom, but he spares a few words for Richard G. Morriss, Sr. and his unnamed daughter: “When this occurrence took place the father and daughter were in their room upstairs.”

A message went out “forthwith” to the families, and they arrived early the next morning. The Republican could not really capture the scene that followed, but tried: “The news of so dreadful the tragedy of course created the greatest excitement and regret in this community. As to the feelings of the unhappy families involved, whose cup of grief has been perhaps forever embittered, we shall not attempt a description. Language would be inadequate to the task.”

“We shall not attempt a description”

Those early articles are doing several things at once. They give readers the “facts” as reporters in Lynchburg, Lovingston, and Richmond understood them. They insist on everyone’s respectability. They assure the “community” that its own sympathies are understood. And they draw a line at how much a family’s private grief will be exposed to public view.

“We shall not attempt a description” is more than a rhetorical flourish. It tells us that the editor has heard stories about the Morriss daughter’s screams, the father’s shock, and the stunned looks on the faces of witnesses—and has decided that these belong, at least for now, inside the family.

In the next installment, those boundaries will not hold. Witnesses from Lovingston, writing in their own voices, will begin to describe exactly what they saw and heard in that dining room, and Capt. Morriss will push back against suggestions that his son was the true aggressor.

Next: Part 2, “Who Fired First?” – Lovingston’s witnesses, a father’s defense, and a grave at Traveller’s Rest.

[1] Richmond Daily Times, 7 July 1851, (Richmond, VA), p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[2] Lynchburg Daily Virginian (Lynchburg, VA), 3 July 1851, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[3] 1850 United States Federal Census, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Eastern, Amherst, Virginia; Roll: 933; Page: 139a; www.ancestry.com

[4] 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules, The National Archive in Washington Dc; Washington, DC; NARA Microform Publication: M432; Title: Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; www.ancestry.com

[5] 1850 United States Federal Census, The National Archives in Washington, DC; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; Series Number: M432; Residence Date: 1850; Home in 1850: Eastern, Amherst, Virginia; Roll: 933; Page: 139a; www.ancestry.com

[6] 1850 U.S. Federal Census – Slave Schedules, The National Archive in Washington Dc; Washington, DC; NARA Microform Publication: M432; Title: Seventh Census of the United States, 1850; Record Group: Records of the Bureau of the Census; Record Group Number: 29; www.ancestry.com

[7] Lorenzo Williams, Class of 1850, Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, PA, U.S., College Student Lists, 1763-1924, American Antiquarian Society; Worcester, Massachusetts; College Student Lists; www.ancestry.com

[8] Craig, P. Steven. (2026, February). Illustration of the Elopement from Lynchburg, 1851 [Concept by author, rendered with AI assistance]. Perplexity AI (GPT Image 1).

[9] Lynchburg Daily Virginian (Lynchburg, VA), 3 July 1851, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[10] Richmond Daily Times, 7 July 1851, (Richmond, VA), p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[11] Böÿe, H., Buchholtz, L. V. & Tanner, B. (1859) A map of the state of Virginia, constructed in conformity to law from the late surveys authorized by the legislature and other original and authentic documents. [Virginia: s.n] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/99439988/.

[12] Craig, P. Steven. (2026, February). Illustration of the McCaul’s Tavern gunfight and aftermath, 1851 [Concept by author, rendered with AI assistance]. Perplexity AI (GPT Image 1).

hello Craig, I’ve tried to follow you on instagram, without success. I’m a direct descendant of Michael Holland so we are distant cousins. Would love to correspond.

LikeLike

Glad to hear from you. You can email me at stevecraig@comcast.net anytime.

Steve

LikeLike