If you missed Justice Delayed Is Justice Denied, Part 1: Essex and Sall . . . and Their Increase, catch up here: https://wp.me/pds3iA-oI

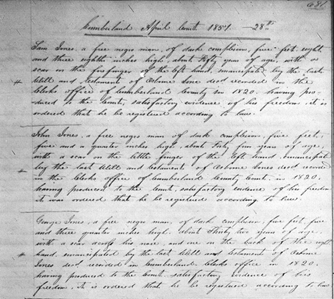

In March 1851, a Cumberland County jury finally admitted what Osborne Jones had written into his will three decades earlier: Sam, John, and George Jones had been legally entitled to freedom since 1829. The jurors declared each man free and awarded each of them a grand total of one cent in damages for more than twenty years of stolen life.

While Sam and John Jones slip quietly out of the surviving records, George Jones does not. What follows is the story of a man who refused to accept a version of “freedom” that required him to abandon the only home he had ever known. By staying he risked being sold back into enslavement, which suggests a compelling motive for remaining. Was it family? Or something else entirely?

Freedom on the Clock

Part 1 ended with the jury’s verdict and the terse entries that recorded Sam, John, and George as free Black men: dark complexions, scars carefully noted, heights measured down to the quarter inch. For George, the clerk wrote: “about thirty-two years old, with a scar across his nose and another on the back of his right hand,” emancipated under Osborne Jones’s 1820 will and now duly registered.

Under the law Virginia adopted in 1806, that registration came with a deadline. Newly emancipated Black Virginians were required to leave the state within twelve months unless the General Assembly passed a special act allowing them to stay; those who remained without such leave risked being seized and sold for the benefit of the state.[1] George’s “freedom,” in other words, came with a ticking clock and a deadline.

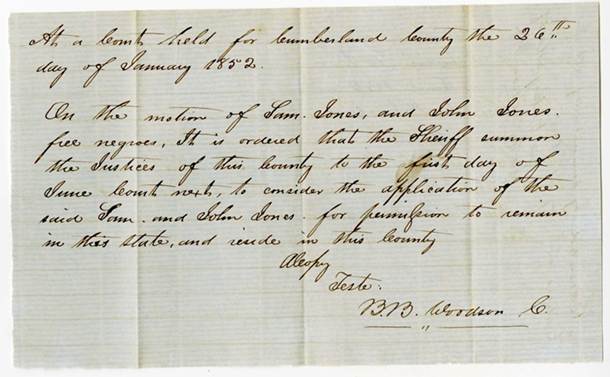

On 26 January 1852, nine months after the verdict, Sam and John asked the Cumberland County Court for leave to remain in Virginia. The court ordered that the justices be summoned to consider their application at the June term, but no further record survives – no recommendation sent on to Richmond, no legislative petition bearing white signatures vouching for them.

George Jones filed no such application – perhaps he knew better. What could he expect from a community complicit in his family’s being illegally held in slavery, a community that described them as “rebellious,”, “disobedient,” and “corrupting,” and that they wanted them out of the “neighborhood?”

From Rural Cumberland to River City

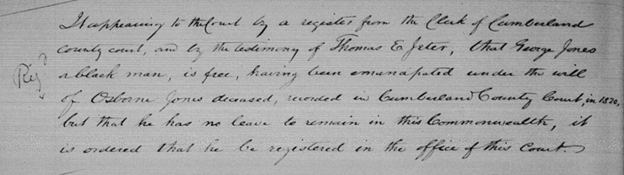

On 10 June 1851, less than two months after receiving his free papers in Cumberland, the Richmond City Court noted:

“It appearing to the Court by a register from the Clerk of Cumberland County Court , and by the testimony of Thomas E. Jeter,[3] that George Jones a black man, is free, having been emancipated under the will of Osborne Jones deceased, recorded in Cumberland County Court, in 1820, but that he has no leave to remain in this Commonwealth, it is ordered that he be registered in the office of this Court.”[4]

The court took no further action; George’s deadline would not expire until March 1852.

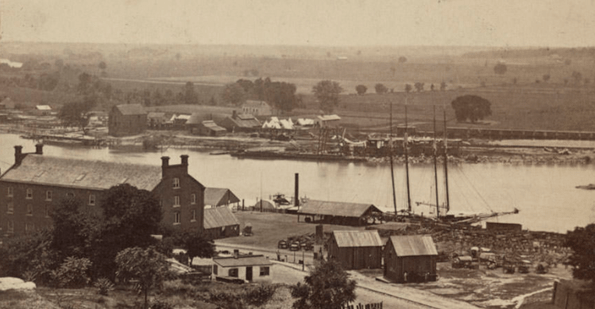

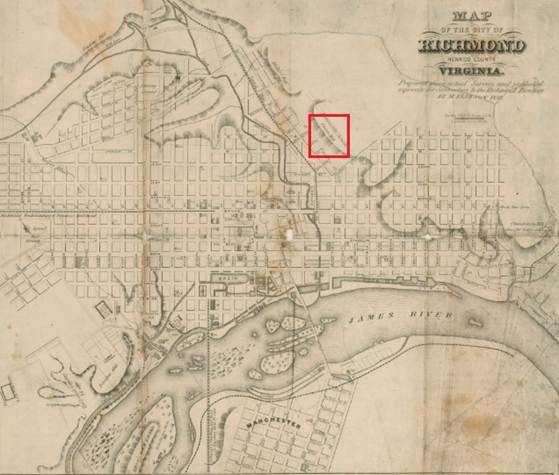

Richmond, the capital city, offered something entirely different. In 1850 the city’s population of roughly 43,000 included about 15,000 white residents, fewer than 10,000 enslaved people, and more than 17,000 free Black residents – a demographic profile completely different that Cumberland’s overwhelmingly enslaved countryside.[6]

Richmond was also a transportation hub; canal boats worked along the James River and Kanawha Canal, rail cars came and went, and coastal vessels carried flour, tobacco, iron and passengers between the capital and ports up and down the East Coast.[8] Richmond was home to numerous markets where innumerable Black men, women and children were hired out locally or sold into the Deep South.[9]

Surviving sources do not tell us how he made his way in those first months, but the city’s labor market narrowed his options. For a newly freed man in his early 30s with no documented white patrons, the best paying work would have been physically demanding and insecure: sweeping streets, loading and unloading freight on the canals and at the riverfront, laying track or grading roadbed, or hiring out to farmers on the city’s fringe.

The fragments of evidence suggest that George gravitated toward the waterfront. By the mid‑1850s, court documents described him as working on a vessel “plying between Richmond and Baltimore,” and show him asserting that he lived in Maryland while serving as crew on that route.[10] He appears to have settled in the Union Hill neighborhood, a modest, economically and racially mixed community whose residents were tied to the nearby Shockoe Valley warehouses and the James River waterfront.[11]

It was an environment rich in both possibilities and risks. Maritime labor was one of the few spaces where Black men could move – literally and figuratively – between slave and free jurisdictions. For a man whose freedom had been delayed for 22 years, the James River and the Chesapeake Bay offered both routes out and a place to blend in while he decided his future. The record is silent as March 1852 came and went, but George chose to stay.

“Disorderly”: A Rock and 39 lashes

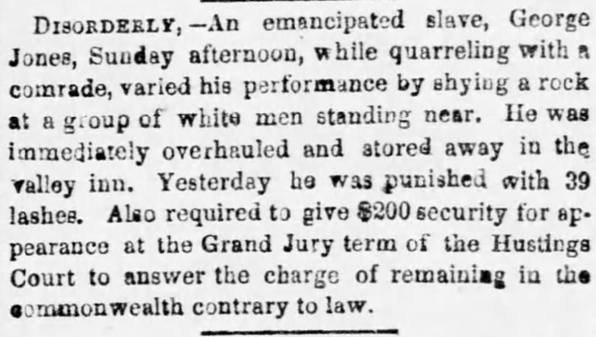

On Sunday afternoon, 28 November 1852 – seven months after his one-year deadline to leave Virginia had expired – George was quarreling with another Black man when, for reasons the sources never explain, he “varied his performance by shying a rock at a group of white men standing near.” The whites seized him immediately and hauled him to the “Valley Inn,” an apparent euphemism for one of the numerous holding pens, jail and other places of confinement in the Shockoe Valley. [13]

The Richmond Dispatch reported the consequences in a brief paragraph, under the heading “DISORDERLY”: George – described pointedly as “an emancipated slave” – was punished with 39 lashes and required to give $200 security for his appearance before the Hustings Court grand jury “to answer the charge of remaining in the commonwealth contrary to law.”[14] In one sentence, the paper connected his spontaneous act of defiance on a Sunday afternoon to the state’s determination to rid itself of people like him. A white man named William H. Eggleston[15] put up the $200 bail, and George was scheduled to appear in court on 14 February 1853.[16]

George’s outburst may have been impulsive, but the legal response was methodical. The court treated the rock‑throwing as a minor disturbance to be addressed through corporal punishment and immediately pivoted to the larger question:

Why was this emancipated man still in Virginia at all?

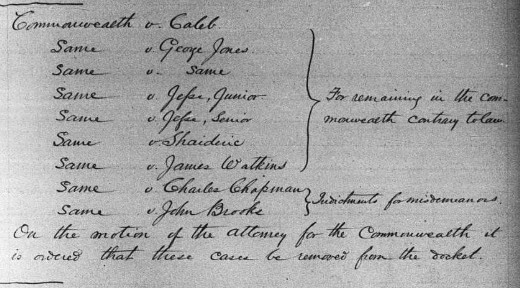

On 18 February 1853, a grand jury in the Hustings Court (Richmond) returned a presentment against George Jones “for remaining in the Commonwealth without leave,” formalizing the charge.[18] The following day, he appeared in court, pleaded not guilty, and the case was continued.[19] The following month, George Jones, by his attorney John N. Davis, appeared in court and tendered an undefined special plea, which the court rejected. His attorney then tendered a bill of exceptions, which the Court received and made part of the record. George was taken into custody.[20] At George’s request, the case was continued through March and April.[21] [22]

A Novel Defense: Selling Himself to Stay

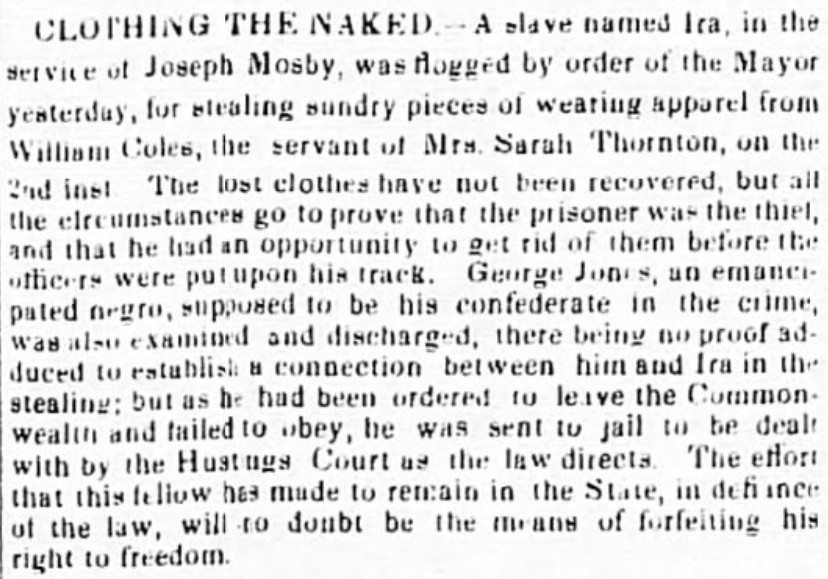

Somehow George managed to get himself released, but he was soon before the court again. On 7 October 1853, city authorities arrested an enslaved man named Ira, enslaved by Joseph Mosby, on suspicion of stealing an overcoat, dress coat, pants, and several vests from another enslaved man. George Jones, suspected of receiving the stolen clothing, was arrested as well.[23]

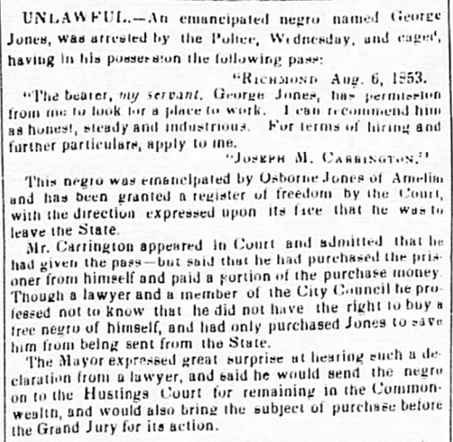

The mayor’s court could not prove that George had knowingly received the stolen property, and he was acquitted on that charge. But as reporters made clear, the case did not end there. In his pockets, officers found a pass dated 6 August 1853 that read:

“The bearer, my servant, George Jones, has permission from me to look for a place to work. I can recommend him as honest, steady and industrious. For terms of hiring and further particulars, apply to me. Joseph M. Carrington.”

When questioned, George told the mayor he was a slave of Carrington, a Richmond lawyer and city council member. The problem was that the Hustings Court register still listed him as a free man, emancipated by the will of Osborne Jones and ordered to leave the state.

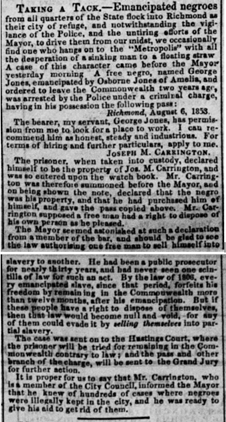

Summoned to explain, Carrington offered an audacious answer. According to the city’s newspapers, he admitted that George had been emancipated but said that George had “sold himself” to him and that he had paid for this self‑sale in installments. He claimed to have believed that “a free man had a right to dispose of his own person as he pleased,” and insisted that he had acted to save George from being forced out of Virginia.[24]

The mayor, who said he had served as a public prosecutor for nearly thirty years, was astonished. He told Carrington he had never seen “one scintilla of a law” that would authorize a free man to sell himself back into slavery, and he pointed out that George’s register contained an explicit injunction ordering him to leave the state. If such self‑sales were allowed, the mayor warned, then the entire legal machinery for forcing emancipated people out of Virginia would collapse.[25]

Two different newspapers highlighted the implications. One described Carrington as professing ignorance that he had no right to “buy a free Negro of himself” and noted that he claimed to have acted only “to save him from being sent from the state.” Another reported that Carrington was ready to help crack down on other cases in which free people were being illegally kept in the city and boasted that he knew of “hundreds” of such examples. In both accounts, George Jones appears as a test case: a man whose determination to stay had pushed him to conspire with an affluent to invent a private workaround to the state’s ban on remaining.

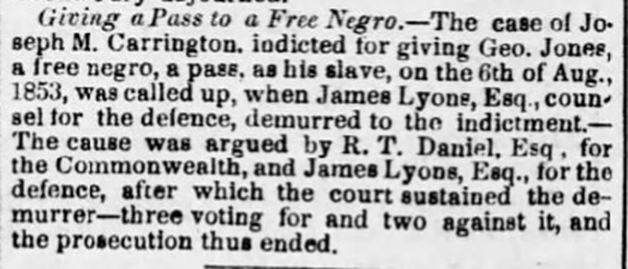

The mayor ordered George to be committed to jail on the charge of remaining in the Commonwealth and sent the question of the forged master‑servant relationship to a grand jury. In November 1853 a jury presented George for remaining and Carrington for issuing the written pass that allowed him to pass as a slave.[26] A year later, the court sustained Carrington’s lawyer’s demurrer and dismissed his case, ending the prosecution against the lawyer. George, meanwhile, continued to face the same underlying charge: he was still in Virginia.

By then, George’s determination to remain in Virginia had acquired a reputation of its own. One newspaper, describing the theft case and George’s recommitment for remaining in the state, concluded with a line that pointed toward the future:

“The effort that this fellow has made to remain in the State, in defiance of the law, will no doubt be the means of forfeiting his right to freedom.”[27]

Refusing to Go: The Law Stalls

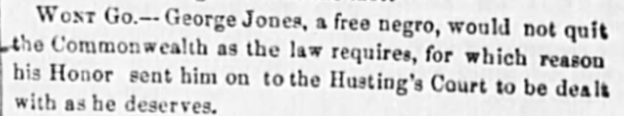

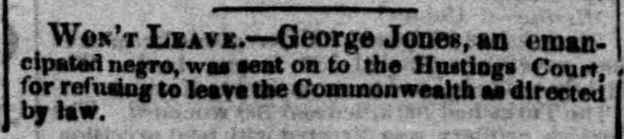

The records from 1854 show the courts’ frustration deepening. In March, George Jones – now regularly described as “an emancipated negro” – was again sent to the Hustings Court “for refusing to leave the Commonwealth as directed by law.”[28] Another notice, titled “WON’T GO,” made the point more bluntly: George “would not quit the Commonwealth as the law requires,” so the mayor sent him on to be “dealt with as he deserves.”[29]

Behind these small items lay a long procedural tangle. The Hustings Court minutes show George appearing in February 1853, pleading not guilty, and having his case continued. In March and April 1854 the court again continued the prosecution at George’s request. Each delay bought him more time on Virginia soil. Each continuance kept the legal question technically open while leaving his life in limbo. The record then falls silent for more than three years.

“The Negro Has Been North.”

On 14 December 1857, the Richmond Dispatch reported that George Jones had been indicted again for remaining in the Commonwealth.[30] By June, a Henrico County grand jury presented George, formalizing the charge. The reporter noted that “the law provides that they shall, upon conviction, be sold into slavery.” [31]

At some point during this period, George lost his original freedom papers, later telling the court that it had been “accidentally lost” – a claim a Cumberland County court accepted in December 1858 when it issued him a renewed copy. Once again, his physical appearance is described: “George Jones, a free negro man of dark complexion, five feet, and one quarter of an such high, about Thirty four years of age with a scar across his nose.”[32]

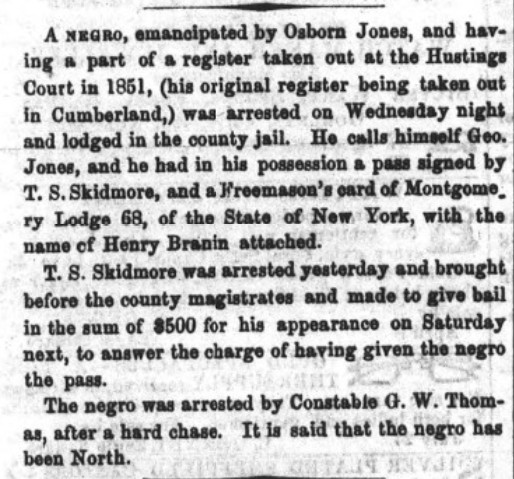

In the meantime, the absence of that document gave Henrico authorities another pretext to detain him. During one of these arrests, in November 1858, constables searching George found a pass signed by a man named Thomas Skidmore and a Freemason’s card from Montgomery Lodge No. 68 in New York, bearing the name Henry Branin. Skidmore was arrested and required to post a $500 bond for issuing the pass, though the county court later discharged him for want of jurisdiction because he was a city resident.[33]

The newspapers noted another suggestive detail: “It is said that the negro has been North.” Who he met there, and what he did, the record does not say. But the image is clear: George Jones, a man Virginia law insisted should be gone, moving between jail cells, courtrooms, city streets, vessels and Northern contacts, stitching together a fragile life out of documents, rumor, and sheer persistence.

“A Notorious Free Negro”

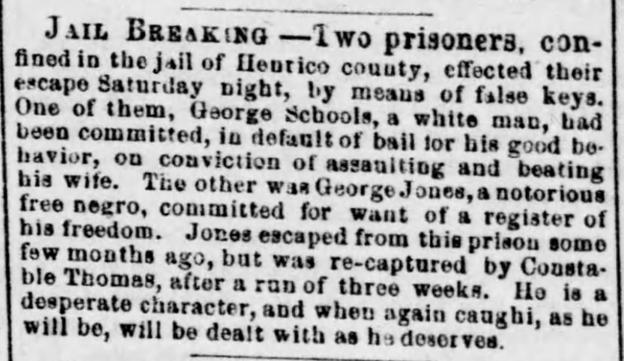

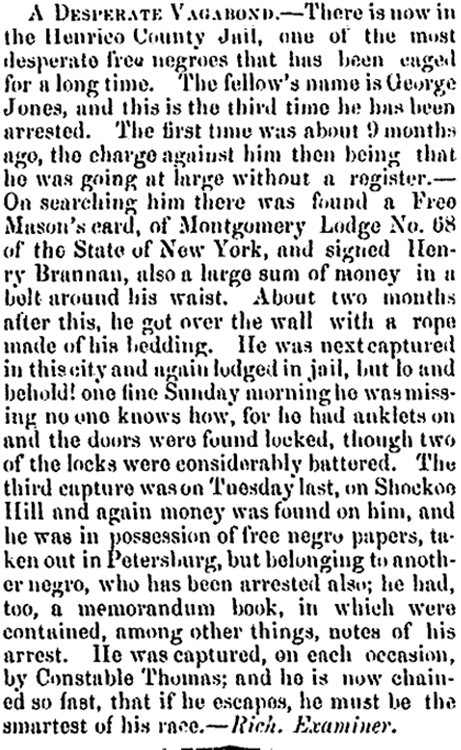

By early 1859, Henrico County officials had begun to describe George in language that echoed the way white neighbors once spoke of his father Essex. In March, after he and a white prisoner named George Schools escaped from the county jail using false keys, a newspaper called George “a desperate character” and warned that, when caught, “he will be dealt with as he deserves.” A few months later another paper labeled him “one of the most desperate free negroes that has been caged for a long time,” emphasizing that this was the third time he had been arrested and recounting his previous escapes in detail.

The same article offered a more revealing inventory. When first arrested with the Skidmore pass, officers found on him not just a Freemason’s card from a New York lodge, but also a large sum of money in a belt around his waist, and later, free papers taken out in Petersburg but belonging to another man, who was also arrested. A memorandum book found on George contained “notes of his arrest,” suggesting a man who tracked his own encounters with authority perhaps as carefully as they tracked him.

By then, Henrico’s court had grown determined to resolve his case. In August 1859 it ordered the clerk of the Richmond Hustings Court to bring George’s original register into evidence as “material” to the prosecution for remaining in the Commonwealth contrary to law.

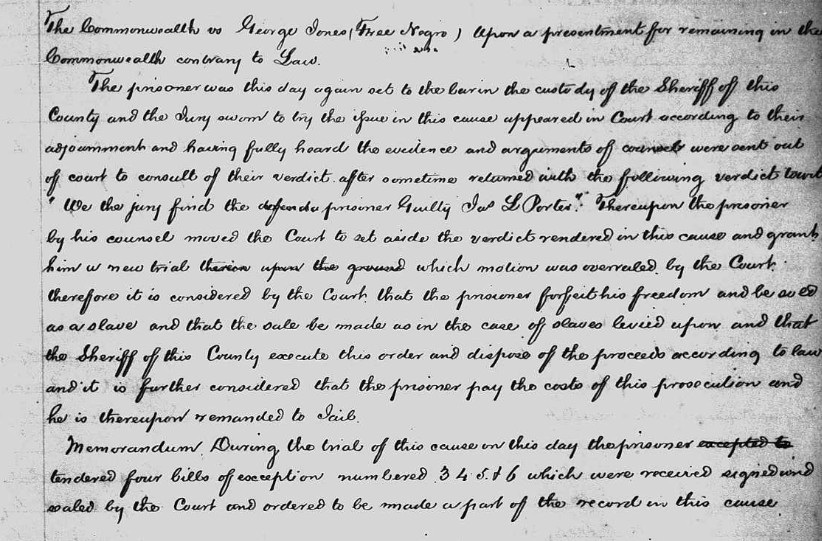

Later that month, a jury found George guilty, and the court sentenced him to forfeit his freedom and “be sold as a slave,” directing the sheriff to sell him according to law.[34] After nearly a decade of resisting the state’s efforts to expel him, George Jones saw the legal freedom he had finally secured in 1851 stripped away.

Chains Dangling on Dock Street

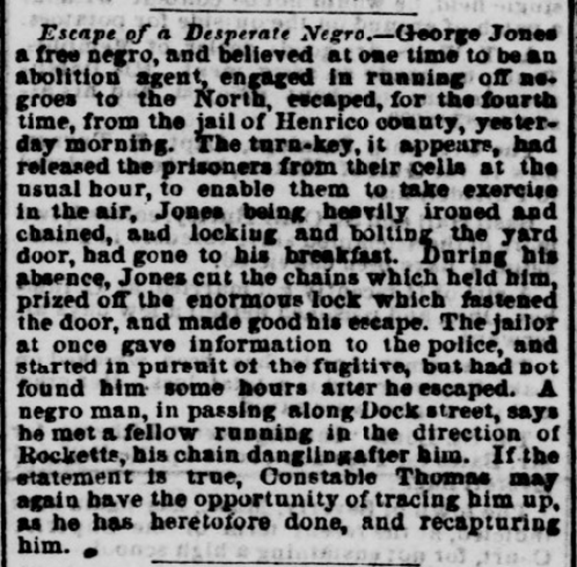

But that is not the end of the story. In June 1860 the Daily Dispatch reported that George—now described as “a free negro, and believed at one time to be an abolition agent, engaged in running off negroes to the North” – had escaped yet again from the Henrico jail.

The jailer had released the prisoners from their cells to exercise in the yard, with George heavily ironed and chained. While the jailer ate breakfast, George cut his chains, pried the lock off the yard door, and fled, his chains “dangling after him” as he ran along Dock Street toward Rocketts landing on the Richmond waterfront.

Jack Sheppard on the James

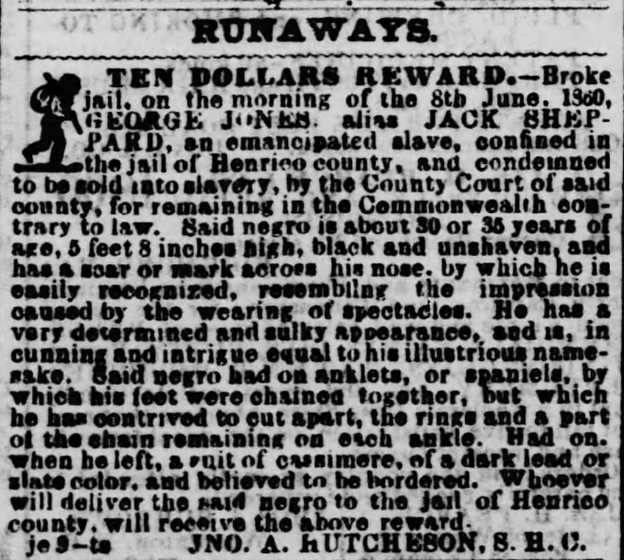

Two days later a reward advertisement appeared under the headline “RUNAWAYS,” offering ten dollars for the capture of “GEORGE JONES, alias JACK SHEPPARD,” an emancipated slave condemned by the Henrico County Court to be sold for remaining in the Commonwealth contrary to law.” The notice described him as 30 or 35 years old, five feet eight inches tall, black and unshaven, with a scar across his nose “resembling the impression caused by the wearing of spectacles,” a “determined and sulky appearance,” and anklets with remnants of broken chains still attached.

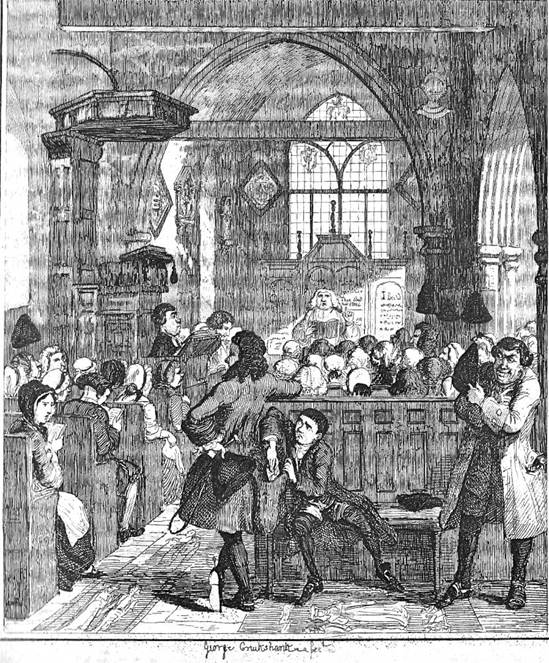

By this point, other sources had begun to specify the kind of work George did. Court papers place him on a vessel “plying between Baltimore and the City of Richmond,” working in the coastal trade as a “blackjack” – a term used for Black sailors and deckhands who labored on schooners and steamers.[35] In Richmond, that occupational label sat uncomfortably close to the alias white writers pinned on him after his repeated escapes: Jack Sheppard, the famous English burglar and escape artist whose exploits filled nineteenth‑century plays and cheap novels, and who would have been very familiar to white readers.[36]

Together, these fragments invite a bit of wordplay: George Jones worked as a Black jack – George Jones was runaway Jack Sheppard – was George Jones a Black Sheppard?

It would be a leap to call him an Underground Railroad conductor outright, yet the pieces line up suggestively – his maritime mobility, large sums of money, borrowed papers, Masonic ties to New York, the ability to afford lawyers, and the Richmond rumors that he had been “an abolition agent, engaged in running off negroes to the North.” Whatever specific role he may have played, his working life placed him squarely in the same maritime world that quietly ferried countless fugitives toward freedom.[38]

From Sale Block to Vanishing Act

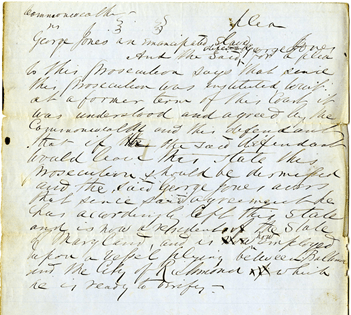

If Henrico’s sentence of sale marked the low point of George’s legal fortunes, the months that followed show him exploiting every remaining crack in the system. In August 1859, as his case made its way through appeals, he tendered a special plea stating that, after the prosecution began, he had left Virginia and become a resident of Maryland, working on a vessel “plying between Baltimore and the City of Richmond.” The court refused to accept the plea, but the document preserves the argument he wanted to make: that his life as a maritime laborer moving between jurisdictions had legally altered his status.

The Henrico minute books record that during his August 1859 trial he submitted multiple bills of exception challenging the court’s rulings, and that after the jury returned its guilty verdict his counsel moved unsuccessfully for a new trial. The county then ordered that he be sold as a slave and remanded him to jail. In April 1860, the court approved a $20 payment to Constable George W. Thomas “for apprehending George Jones (a free negro), on two occasions after he had escaped from the Jail of this County,” a small hint at the time and effort his recaptures required.

The June 1860 escape and “Jack Sheppard” advertisement show that even heavy irons and chained anklets could not keep him confined. The description of him running with chains rattling down Dock Street toward the riverfront – toward the ships and wharves that had given him his partial freedom – captures both his desperation and his ingenuity.

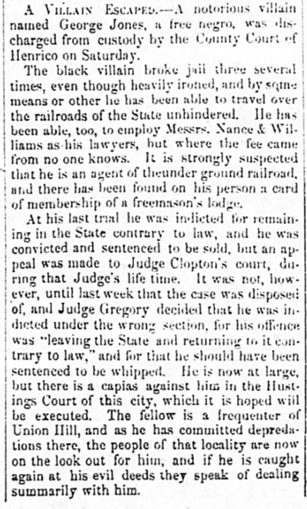

Captured once again, a November 1860 article published by the Richmond Enquirer announced that “a notorious villain named George Jones, a free negro, was discharged from custody by the County Court of Henrico on Saturday.” The paper reviewed his escapes, his ability to travel over the railroads “even though heavily ironed,” and the fact that he had retained attorneys Nance & Williams, though “where the fee came from no one knows.” It repeated the suspicion that he was “an agent of the underground railroad,” noted again the Masonic card found on his person, and explained why he had been released.

At his last trial, the article reported that George had been indicted for remaining in the state contrary to law and sentenced to be sold. But his appeals had gone up to the circuit court, and Judge Gregory ultimately ruled that he had been indicted under the wrong section of the statute. His true offense, in the judge’s reading, was not simply remaining after emancipation but “leaving the State and returning to it, contrary to law,” for which the penalty should have been whipping rather than sale. On that technical ground, the court ordered his discharge from the county’s custody.

The Enquirer closed with a warning. George, it explained, was “now at large,” but there was still a capias against him in Richmond’s Hustings Court, and residents of Union Hill—where he was well known and had allegedly “committed depredations” – were “on the lookout for him” and spoke of “dealing summarily with him” if he returned to his old habits. Not if they found him – if he returned to his old habits.

Four years later, in January 1864, the Hustings Court, without explanation, removed George’s case from its docket at the request of the Commonwealth’s attorney, marking the last known official mention of his name.[39]

What Might have Kept Him Here

The sources do not tell us why George clung so fiercely to Virginia, even when staying meant whippings, chains, and the constant risk of sale. One naturally thinks a familial connection may have held him – an enslaved wife and children, perhaps. But in all the newsprint about George Jones, not a whisper of any personal relationship. If not that, what?

Part 1 showed how deeply his family’s story was rooted in Virginia soil. Essex and Sall had survived efforts to sell them “to New Orleans, or the South,” endured patrol raids and criminal prosecutions, and watched white neighbors describe them as “rogues” and “threats.” Osborne Jones’s will had tied their promised freedom to Betsy Jones’s lifespan, and when that freedom finally came due in 1829, local whites found ways to ignore it for more than two decades. George’s entire childhood and young adulthood unfolded inside that betrayal. His father’s continued resistance, and the punishments he received for his attempts, must have made a strong impression.

By the time he won his case in 1851, the state was using its own laws to convert emancipation into exile. Leaving Virginia may have looked, to him, like a continuation of the same pattern: the people who had stolen his labor now insisting that freedom meant disappearing. Staying – working on the docks, signing on to coastal vessels, slipping in and out of jurisdictions, testing the limits of passes and free papers – offered a different kind of claim, however precarious: a determination to live on his own terms.

Hints of abolitionist connections complicate the picture. If, as one paper believed, he had at some point served as “an abolition agent, engaged in running off negroes to the North,” the choice to remain in Virginia would have carried not only personal but political meaning. The Chesapeake’s maritime routes were lifelines for enslaved people seeking freedom, and free Black sailors and laborers played crucial roles in carrying news, forging contacts, and sometimes physically assisting escapes.[40] Even if the accusation exaggerates his role, the fact that contemporaries believed it suggests that he moved in circles where such work was imaginable.

It is also possible that George’s determination grew from the same stubbornness whites once ascribed to his father. Essex was described as a “desperate character,” accused of harboring runaways and stealing hogs, and repeatedly targeted by patrols and local justices. Henrietta Vaughan and her neighbors feared not just his actions but his influence on others, worrying that he and his family were “corrupting” the enslaved people around them. If George inherited anything from his parents beyond scars and a last name, it may have been a refusal to comply quietly with a system that simply asked too much.

An Ending Without an Ending

After 1864, the official trail runs out. After everything he endured, I find it hard to imagine that George Jones chose to leave Virginia for good. In a flood of post‑emancipation records, there are many Black men named George Jones, some of them roughly the right age, living in Richmond and Henrico. Others appear in Chesterfield, Manchester, Amelia, Nottoway, and Petersburg. Further away, more than one Black George Jones appear in Baltimore. Sadly, none can be linked with certainty to the man whose life we have traced here.

In Part 1, justice delayed meant that Essex and Sall died enslaved and that their children spent more than twenty years in bondage after their legal emancipation date. In Part 2, justice denied takes another form: a man forced to fight, simply for the right to remain in his home state. Records cannot confirm that intuition, but the life they reveal – scarred, stubborn, sometimes reckless, and always in motion – suggests a man who, having finally claimed his freedom, intended to hold on to it in the only place that ever truly belonged to him. A son of Virginia until the end.

[1] “An ACT to amend the several laws concerning slaves,” was passed by the General Assembly on January 25, 1806, and prohibited the importation of slaves to Virginia and required that any freed slaves leave the state within twelve months.” Samuel Shepherd, ed., The Statutes at Large of Virginia, from October Session 1792, to December Session 1806 (Richmond: Samuel Shepherd, 1836), 3:251–253., Encyclopedia Virginia; https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/an-act-to-amend-the-several-laws-concerning-slaves-1806/

[2] Jones, Samuel : Petition to Remain in the Commonwealth, Cumberland County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1753-1865 , Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://lva.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01LVA_INST/br4o1h/alma9917832401105756

[3] Thomas E. Jeter (1806-1853) was a native of Amelia County, Virginia, son of Tilmon Ellison and Sarah (Webster) Jeter; Richard T Jeter, Etc. & John W Knight vs. Admr. Of Tilmon E Jeter, Etc., Amelia County, Virginia Chancery Cause, Index No. 1874-007, Digital Collections, Library of Virginia; https://old.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=007-1874-007

[4] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes No. 19, 1850-1852, p. 287; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-XS6Y-2?view=explore : Jan 27, 2026), image 189 of 324; Image Group Number: 008574657

[5] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes No. 19, 1850-1852, p. 287; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-XSCS-D?view=explore : Jan 28, 2026), image 188 of 324; Image Group Number: 008574657

[6] U.S. Census Bureau, 1850 Virginia Census Report; https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1850/1850a/1850-census-report-virginia.pdf

[7] What Richmond, VA looked like in the 1860s Through these Rare Historical Photos, Bygonely; https://www.bygonely.com/richmond-1860s/

[8] 1825-1861, The Growth of Industry, The Story of Virginia, Virginia Museum of History & Culture; https://virginiahistory.org/learn/story-of-virginia/chapter/growth-industry?utm_source=copilot.com

[9] Enslavement in Richmond and the Region, 1830-1865, An Unfolding History, University of Richmond; https://unfoldinghistory.richmond.edu/

[10] Commonwealth vs. George Jones, Commonwealth Cause, 1864, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, Digital Collections, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia; https://virginiahistory.org/learn/story-of-virginia/chapter/growth-industry?utm_source=copilot.com

[11] The Union Hill Historic District, Church Hill People’s News, 22 November 2009, https://chpn.net/2009/11/22/the-union-hill-historic-district/; adapted from application for historic district recognition available at the Virginia Dept. of Historic Resources; https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/historic-registers/127-0815/

[12] Sides, William, “Map of Richmond, Ellyson, 1856,” Online Exhibitions, accessed January 27, 2026, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/events/exhibitions/online/oe/items/show/2.

[13] Richmond Dispatch, Tue, Nov 30, 1852, Page 2; www.newspapers.com

[14] Richmond Dispatch, Tue, Nov 30, 1852, Page 2; www.newspapers.com

[15] William H. Eggleston (1811-1885), son of Benjamin and Mary Ann Eggleston. Tobacconist, served as a Private in Company F, 1st Virginia State Reserves. Interred at Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/148134549/william_h-eggleston

[16] Commonwealth vs. George Jones, Commonwealth Cause, 1864, Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, Digital Collections, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia; https://virginiahistory.org/learn/story-of-virginia/chapter/growth-industry?utm_source=copilot.com

[17] Owens, Cassie. Philadelphia Enquirer, 2 July 2020; https://www.inquirer.com/news/delaware-whipping-post-race-black-removed-georgetown-sussex-county-20200702.html

[18] City of Richmond, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes 20, 1852-1853, p. 246; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-XSCS-7?view=explore : Jan 16, 2026), image 26 of 173; Image Group Number: 008574657

[19] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes, No. 20, 1852-1853, p. 288; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-XSDQ-N?view=explore : Jan 27, 2026), image 27 of 173; Image Group Number: 008574657

[20] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes No. 21, 1853-1855, p. 77; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-VS7G-1?view=explore : Jan 27, 2026), image 83 of 320; Image Group Number: 008574658

[21] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes, No. 21, 1853-1855, p. 112; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-VS72-R?view=explore : Jan 27, 2026), image 101 of 320; Image Group Number: 008574658

[22] Richmond City, Virginia, Hustings Court Minutes, No. 21, 1853-1855, p. 80; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C374-VSHM-L?view=explore : Jan 27, 2026), image 85 of 320; Image Group Number: 008574658

[23] The Richmond Enquirer, Friday, 7 October 1853, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[24] Richmond Enquirer, Fri, Oct 07, 1853, Page 2; www.newspapers.com

[25] Richmond Dispatch, Friday October 7 1853, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[26] Richmond Enquirer, Friday, October 7, 1853, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[27] Richmond Enquirer, Friday, 7 October 1853, p. 2; www.newspapers.com

[28] Richmond Dispatch, Wed, Mar 15, 1854, Page 2; www.newspapers.com

[29] Daily Richmond Whig, Wed, Mar 15, 1854, Page 1; www.newspapers.com

[30] Richmond Dispatch, 14 December 1857, p. 1; www.newspapers.com

[31] South, Volume 2, Number 62, 8 June 1858, p. 3; https://www.virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=SOUTH18580608.1.3

[32] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1858-1859, p. 88; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-QS4Q-T?view=explore : Jan 10, 2026), image 74 of 298; Image Group Number: 008358490

[33] The South, Vol. 2, No. 195, 10 November 1858, p. 2; Virginia Chronicle; https://www.virginiachronicle.com/?a=d&d=SOUTH18581110.1.2

[34] Henrico County Virginia, Court Minute Book 1860-1861, p. 244; “Henrico, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-V36K-KXHS?view=explore : Jan 16, 2026), image 159 of 524; Image Group Number: 008737685

[35] Darius Stanton. Life on the Bay, through ebony eyes, 28 February 2018, Chesapeake Bay Program; https://www.chesapeakebay.net/news/blog/life-on-the-bay-through-ebony-eyes

[36] The Works of George Cruikshanks, 1792-1878, The Victorian Web, https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/works.html

[37] The Victorian Web; https://victorianweb.org/art/illustration/cruikshank/js10.html

[38] Underground Railroad in Virginia, Encyclopedia Virginia; https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/underground-railroad-in-virginia/

[39] Hustings Court Minutes 29, 1863-1866, p. 105; “Richmond, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3M5-J746-X?view=explore : Jan 16, 2026), image 91 of 295; Image Group Number: 008458685

[40] Underground Railroad in Virginia, Encyclopedia Virginia; https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/underground-railroad-in-virginia/

Wh

LikeLike

Speechless Betsy?

LikeLike

Amazing how you can discover so much from so long ago

LikeLike

Your research is almost as remarkable as George’s resilience! I hope someone makes a screenplay from this.

LikeLike

That would be something! I’ll settle for 20 people reading it! Thank you for doing so and for writing. I really appreciate it.

LikeLike