In March 1851, a Cumberland County jury finally agreed that three men—Sam, John, and George—had been legally entitled to freedom for more than twenty years. The jurors awarded them their liberty and one cent each in damages for more than two decades of stolen life.[1]This is the story of how their family’s freedom was promised on paper in 1820, buried under legal maneuvering and local hostility, and only partially reclaimed a generation later. It begins not with Sam, John, and George, but with the will of a white bachelor named Osborne Jones.[2]

Cumberland County, Virginia, 1820 – A Promise of Freedom

This story began while researching Joseph Vaughan, who died about 1825 in Cumberland County, Virginia, the youngest son of Robert and Elsie (Motley) Vaughan of Nottoway County and a collateral ancestor in my Vaughan line (see my earlier blog post on Robert Vaughan II here: https://asonofvirginia.blog/2024/08/11/robert-vaughan-ii-c-1736-c-1805-of-amelia-and-nottoway-counties-virginia/). What began as genealogical research into Joseph Vaughan quickly gave way to a very different narrative.

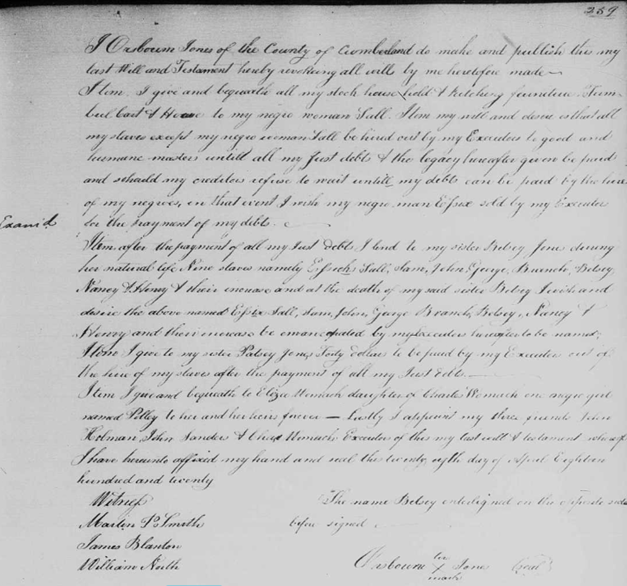

On 27 April 1820, a fifty‑year‑old bachelor named Osborne Jones of Cumberland County was so ill that Dr. Philip Southall Turner of Amelia County was called to consult with local physician Dr. John Spencer about his condition.[3] The next day, 28 April, Osborne Jones dictated an unusual will.[4]

He revoked all prior wills and immediately singled out one enslaved woman:

Item. I give and bequeath all my stock, house hold & Kitchen furniture, Tumble Cart & Horse to my negro woman Sall.

Then he turned to the rest of the enslaved people he owned, including a man named Essex:

Item my will and desire is that all my slaves except my negro woman Sall be hired out by my Executors to good and humane masters until all my just debts & the legacy hereafter given be paid and should my creditors refuse to wait untill my debts can be paid by the hire of my negroes, in that event I wish my negro man Essex sold by my Executor for the payment of my debts.

After debts were paid, Osborne Jones created a life estate for his sister Elizabeth (“Betsy”) Jones and made a promise of future freedom in the same clause:

Item. After the payment of all my just debts I lend to my sister Betsy Jones during her natural life Nine slaves namely Essex, Sall, Sam, John, George, Branch, Betsey, Nancy & Henry & their increase, and at the death of my said sister Betsey, I wish and desire the above named Essex Sall, Sam, John, George, Branch, Betsy, Nancy, Henry and their increase be emancipated by my Executors hereafter to be named.

He added a cash legacy to another sister and a specific bequest for one young girl:

Item I give to my sister Patsey Jones Forty dollars to be fund[ed] by my Executors out of the hire of my Slaves after the payment of all my Just debts.

Item I give and bequeath to Eliza Womack, daughter of Charles Womack, one negro girl named Polley to her and her heirs forever.

Finally, he named three white men—John Holman, John Sanders, and Charles Womack—as executors and signed with his mark. A note in the record indicates that the name Betsey was interlined before signing, reflecting a late addition or clarification.

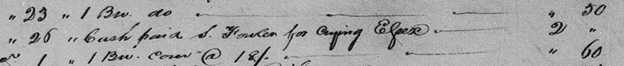

Crying Essex: At the auction block and hired out

Osborne Jones left no money to pay his debts. Executor Charles Womack therefore turned almost immediately to the enslaved people in the estate, beginning with Essex. In the months after Osborne’s death, Womack paid auctioneer Sherwood Fowler for “crying” Essex—that is, publicly offering Essex for sale at auction. Fowler received $2 on 23 November 1820 and another $2 on 26 November 1821, with a .50 cent payment in March 1821 that likely related to advertising the sale.[5]

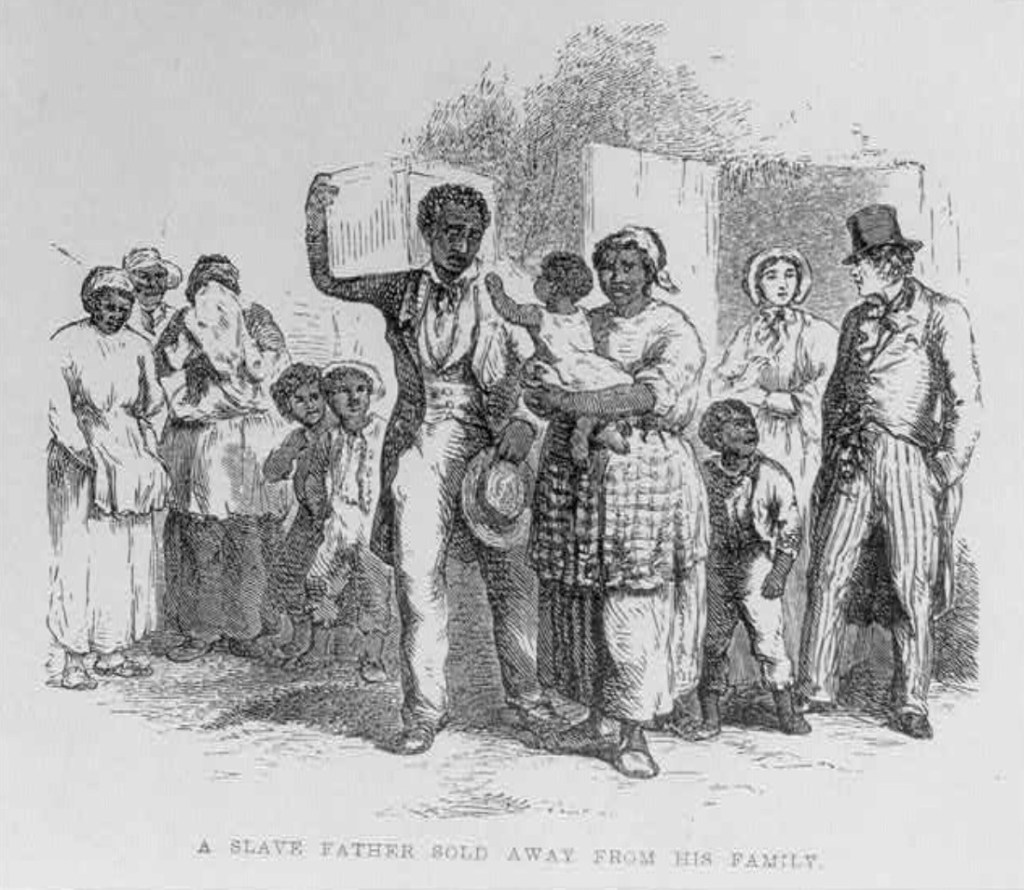

Public auctions of enslaved people were routine in nineteenth‑century Virginia. Essex would have been prepared for inspection—washed, shaved, and oiled—to appear as young and healthy as possible, and then displayed alongside others while potential buyers examined teeth, pinched limbs, made them walk or bend, and watched for signs of disability.[6] Men in their forties like Essex, young mothers with children, adolescent boys, and entire families might be offered together or in lots that could break them apart, with each call of the crier carrying the risk of permanent separation.

In Essex’s case, the sales never went through. Whatever offers were made, Womack evidently found them insufficient and Essex remained unsold. That did not mean safety for Essex or his family. Under the will, the default plan for paying debts and legacies was to hire out every enslaved person except Sall. Essex and his children lived under constant uncertainty: he could still be sold at any time, and all of them could be rented out to strangers year after year.

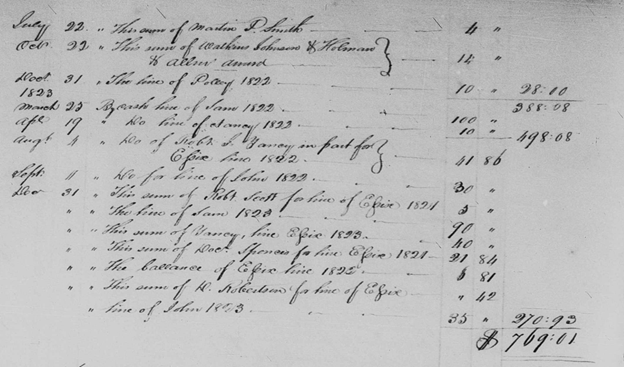

The estate account Womack filed for 1821–1823 show how quickly that system went into effect. It is an extensive document spanning some six pages in the county will book. Essex was hired repeatedly, often for short terms; Sam, John, Nancy, and Polly were typically hired on an annual basis. The entries include, among others, twelve days of hire for Essex at two shillings per day in April 1821, thirty days “to get bark” in June 1821 for $14.67, and multiple payments from men such as Robert Lott, R. J. Yancy, D. Blanton, Robert Scott, and Dr. Spencer for Essex’s labor in 1821–1823. Sam was hired to John McNuckholds for just over two months in late 1820, then again for ten months in 1822 and for the year 1823, while Polly, John, and Nancy appear with annual or multi‑month hire entries in 1821–1823.

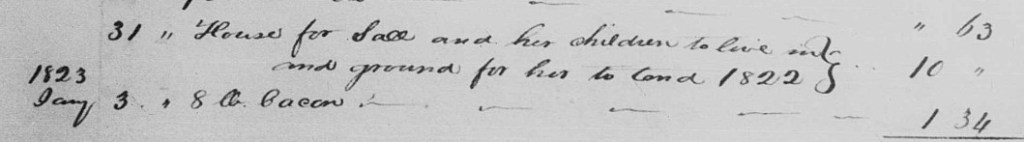

Womack did follow Osborne’s instructions regarding Sall’s living situation. Th estate accounts for 1821–1823 record payments of $10 per year for “house for Sall & her children & ground for her to tend,” as well as $2.30 in January 1821 for “2 days’ work repairing Sall’s house.” On 12 January 1822, Sall sold the horse and cart back to the estate for $24 dollars—$12 for each—converting items she technically owned under the will into cash.

The account is especially detailed when it comes to clothing and shoes. Between late 1820 and 1823, the executor paid for sole leather and the making of Sall’s shoes, two pairs of shoes for Sall and John, seven yards of oznabrig for Sall’s shirts, a coat, hat, blanket, and multiple pairs of double‑soled shoes for Sam, and double‑soled shoes for Essex, with additional payments for Sall’s shoes in 1823. A note in the record clarifies that “the bread, shiffs, &c charged in the foregoing account was for Sall & her 4 children.”

From this, it appears that by the early 1820s Sam, John, George, and Nancy were the children remaining with Sall, or at least the children old enough to be hired out by the estate thus included in the estate account. Polley, who was hired in 1821 and 1822, disappears from later estate accounts. She had been specifically bequeathed to Eliza Womack, daughter of executor Charles Womack, and was not included among those designated for emancipation; it is likely she left the immediate orbit of Osborne Jones’s estate when Eliza married William Lee under a Cumberland County marriage bond dated 6 December 1823.[8]

By the mid‑1820s, then, the will’s promise of emancipation still lay in the future. In the meantime, Sall lived in a house maintained at estate expense, raising at least four children, while Essex and the others were cycled through a web of short‑ and long‑term hires that turned every year of their lives into revenue for the estate’s creditors and heirs.

Sold on paper again

By late 1823, the family’s legal situation changed again. Betsy Jones, who held a life interest in Essex, Sall, and their children under Osborne’s Jones will, sold that life interest to Joseph Vaughan of Cumberland County, the man who had first drawn my attention in this research.

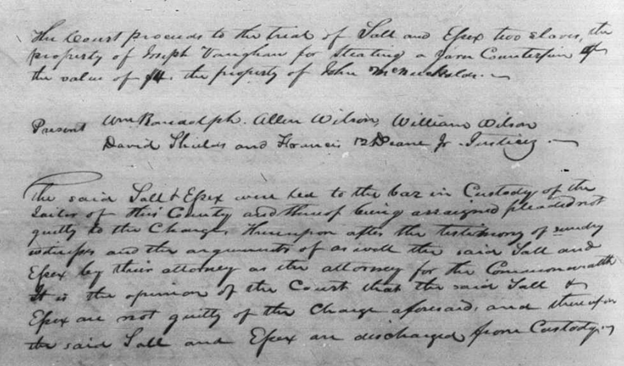

The record of that sale appears indirectly, through a criminal case. On 25 October 1824, the Cumberland County Court tried:

“Sall and Essex two slaves, the property of Joseph Vaughan, for stealing a yarn Counterpin or bed cover valued at 4 dollars and the property of John McNuckolds.”

Sam had previously been hired to McNuckolds, and now Sall and Essex themselves were “led to the bar in custody of the Jailor” and pleaded not guilty. After hearing unrecorded witness testimony and arguments from “Sall and Essex by their attorney” and the attorney for the Commonwealth, the court concluded that Sall and Essex were not guilty and discharged them from custody.[9]

Joseph Vaughan died around 1825. His will, dated 11 July 1823 and recorded in July 1825, left his widow, Henrietta R. Vaughan, in possession of the enslaved people he had acquired—including the family Osborne Jones had intended to free.[10] A few years later, in late 1828 or early 1829, Betsy Jones herself died, which, under Osborne’s 1820 will, should have triggered the emancipation of Essex, Sall, Sam, John, George, Branch, Betsey, Nancy, Henry, and the “increase” born since 1820, which included Allen and Madison.

The will’s promised freedom did not materialize.

When Osborne Jones wrote his 1820 will, he was using a manumission system that had briefly opened after the Revolution but was already under pressure from white fears of Black resistance, especially after Gabriel’s planned uprising near Richmond in 1800. Gabriel’s conspiracy helped produce the 1806 law that forced most newly freed Black Virginians to leave the state within a year, ensuring that emancipation meant exile and deepening white suspicion of free Black communities.[11]

By the time Betsy Jones died around 1829 – when Essex, Sall, and their children should have become free—the climate had grown even harsher. The in 1831, Nat Turner’s revolt in Southampton County sparked a wave of panic.[12] It also caused a statewide debate in which the General Assembly ultimately rejected any move toward ending slavery and instead tightened laws restricting Black movement, assembly, preaching, and manumission.[13]

In that world, a family already labeled “rebellious,” “disobedient,” and “corrupting” would have been exactly the people local whites least wanted to see join the free Black population of Cumberland, making it far easier for executors and heirs to ignore or resist the emancipation Osborne Jones had promised them on paper.

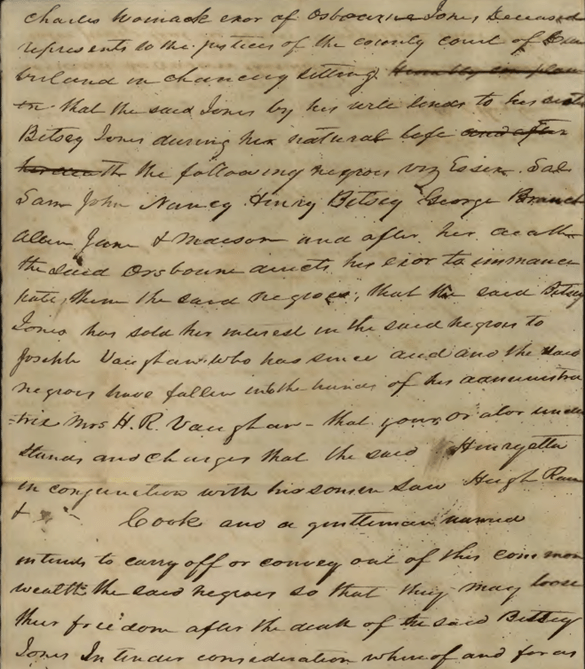

Trying to ship them south

Instead, the record shows an attempt to move the family out of Virginia altogether. On 22 December 1828, Osborne Jones’s executor, Charles Womack, filed a petition in the Cumberland County Court seeking an injunction against Henrietta R. Vaughan, her sons‑in‑law Hugh Raine and John R. Cooke, and Raine’s nephew James Brooks. Womack accused them of planning to “carry off or convey out of this Commonwealth the said Negroes so they may lose their freedom.”[14] The named people included Essex, Sall, Sam, John, Nancy, Henry, Betsey, George, Branch, Allen, and Madison.

After a hearing, the court issued an order restraining the defendants from removing these enslaved people from Virginia and directing the sheriff to take them into possession and keep them safely. The injunction would remain in place until the defendants posted bond guaranteeing that the family would be “forthcoming to abide the Judgment of the court in the premises.”

On its face, the suit framed Womack as the defender of Osborne Jones’s emancipatory clause. The answers filed a month later revealed a more complicated reality.

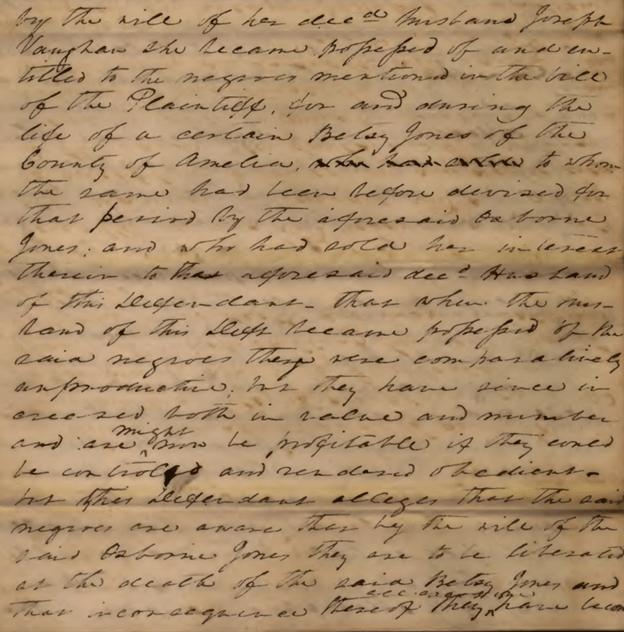

“Disobedient and rebellious”: the white answers

On 23 January 1829, each defendant filed a formal answer denying any intent to sell the family out of state or defraud them of their promised freedom—but their own words undercut those denials. James Brooks admitted that, at Raine’s request, he had helped take the enslaved people who had belonged to Osborne to Richmond with the intention of selling them, but stated that Raine could not get a sale “upon such terms as he thought profitable,” so the group was brought back to Henrietta Vaughan’s plantation.

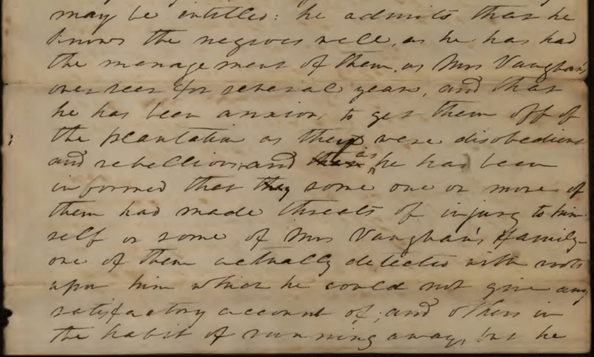

John R. Cooke, Joseph and Henrietta’s son‑in‑law and overseer, stressed that he “knew the Negroes well” from managing them “for several years.” He wrote that he had been anxious to remove them from the plantation because “they were disobedient and rebellious,” that he had been told “some one or more of them had made threats of injury to himself or some of Mrs. Vaughan’s family,” and that some were “in the habit of running away.”

Henrietta Vaughan’s answer was even more revealing. She confirmed that, “by the will of her dec’d husband Joseph Vaughan,” she had become entitled to the enslaved people named in Womack’s bill and that Betsy Jones had sold her life interest to Joseph. She explained that “the said negroes are comparatively unproductive” and would be profitable only if they could be “controlled and rendered obedient.”

Crucially, she acknowledged that Osborne Jones’ will provided for their liberation at Betsy Jones’ death and that the enslaved themselves knew it. She wrote that their awareness of this future freedom had made them so “disobedient and rebellious” that she could not keep them around her other enslaved people, “whom they were daily corrupting by their bad habits.” She said she had consulted an attorney, been advised that she could sell her legal interest, and made no secret of her “determination to sell them,” while complaining that their “character was so bad that no disposition or sale could be affected in the neighborhood where they were well known.”

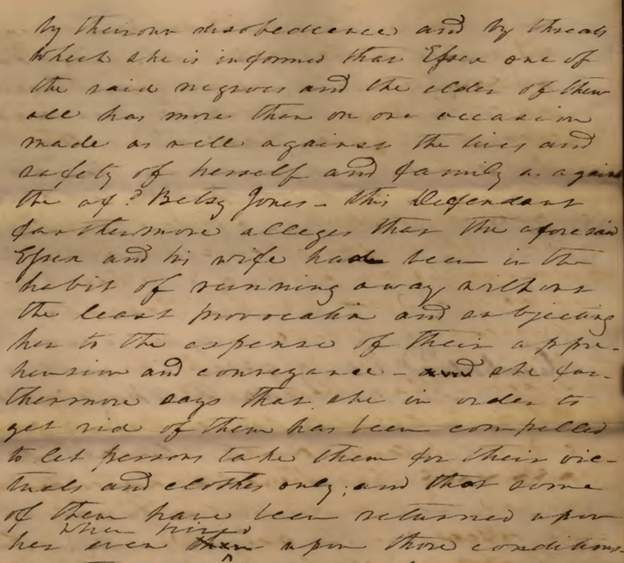

Henrietta Vaughan singled out Essex as “one of the said Negroes, and the elder of them all,” accusing him of repeatedly threatening “the lives and safety of herself and family” and stating that he and Sall “had been in the habit of running away without the least provocation,” forcing her to pay the costs of apprehension and transport. She claimed she had been “compelled to let persons take them for their victuals and clothes only” and that even on those terms some had been returned.

Under Virginia law and local practice, labels like “rebellious,” “disobedient,” and “desperate character” almost certainly meant repeated whippings, physical restraint – sometimes irons or collars – and the constant threat of sale or shipment south. Enslaved people accused of harboring runaways and stealing hogs in this period could be whipped “well laid on” at the whipping post, chained at night, and hired out to harsher masters as punishment.[15]

Hugh Raine, the other son‑in‑law, framed his own actions as purely financial. He wrote that, needing money, he had “attempted to sell the same interest, and none other, which he bought of Mrs. Vaughan”—that is, the life interest he held in the enslaved family until Betsy’s death. He “utterly” denied combining with anyone to “remove the said negroes beyond the limits of the Commonwealth” or to “defraud them of their freedom” at Betsy’s death, but conceded that he had “carried the said negroes to the City of Richmond” to try to sell his interest there. He added that Mrs. Vaughan would only consent if he sold them out of the local neighborhood “such is the prejudice existing against them,” and that, unable to get what he considered a fair price, he brought them back and returned them to Henrietta.

Taken together, these answers show white owners and kin acknowledging both the will’s emancipation clause and the family’s determination not to accept continued bondage quietly, even as they explored how to sell them away before that freedom took effect.

“To New Orleans, or the South”

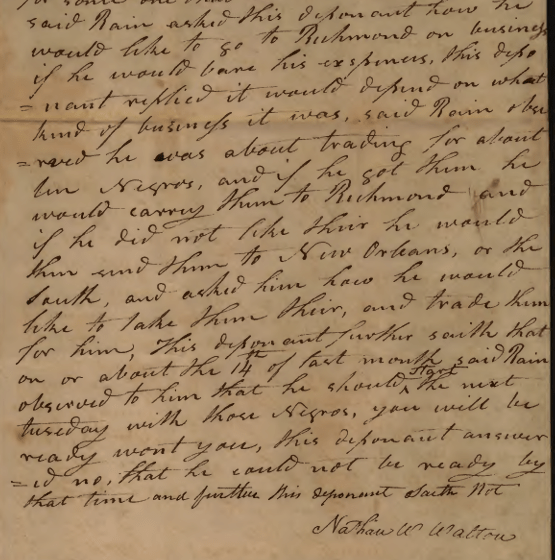

Depositions taken in early 1829 underscored how far they were willing to go. On 26 January 1829, Nathan Walton testified that, in December, he had told Raine he hoped for paid work to cover his travel costs. Raine asked if he would like to go to Richmond on business and, when Walton inquired what kind of business, told him he was “about trading for about ten Negroes” and would carry them to Richmond. Walton recalled Raine saying that if he did not like Richmond prices, “he would then send them to New Orleans, or the South,” and that Raine invited him to accompany him in about a week. Walton declined.

On 7 February 1829, at Peter B. Foster’s tavern, William D. Price testified that Raine had asked about “the prospects” of the Richmond market and “what would be the cost of freight for a parcel of negroes to New Orleans, or to the South.” Price believed Raine left for Richmond with a group of enslaved people around 16 December 1828.

Foster himself testified that he had loaned Raine his “little wagon” under a prior arrangement “for the purpose of conveying a parcel of negroes to Richmond,” whom he understood to be people who had once belonged to Osborne Jones and had been bought by Joseph Vaughan.

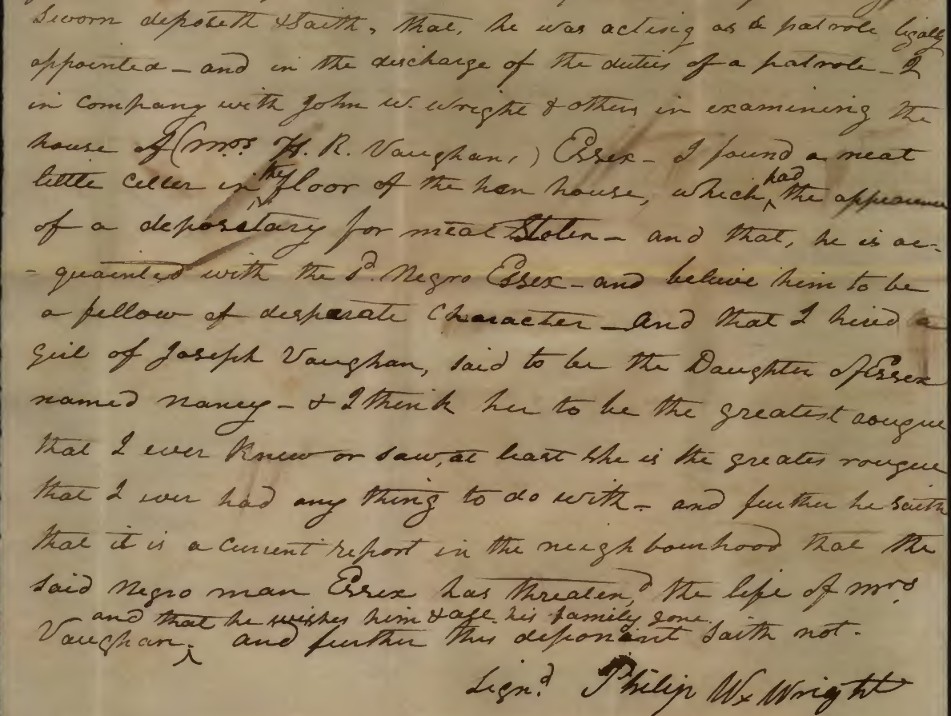

On 18 February 1829, additional depositions were taken at Henrietta Vaughan’s home. Philip W. Wright, serving as a legally appointed patrol, testified that while searching Henrietta’s property with others they found that Essex had “a neat little cellar in the floor of the hen house, which had the appearance of a depository for meat stolen.” Wright called Essex a “fellow of desperate character” and said he had hired a girl identified as Essex’s daughter Nancy, whom he described as “the greatest rogue” he had ever dealt with. He reported that neighborhood “current report” was that Essex had threatened Henrietta’s life and that people wished “him & all his family gone.”

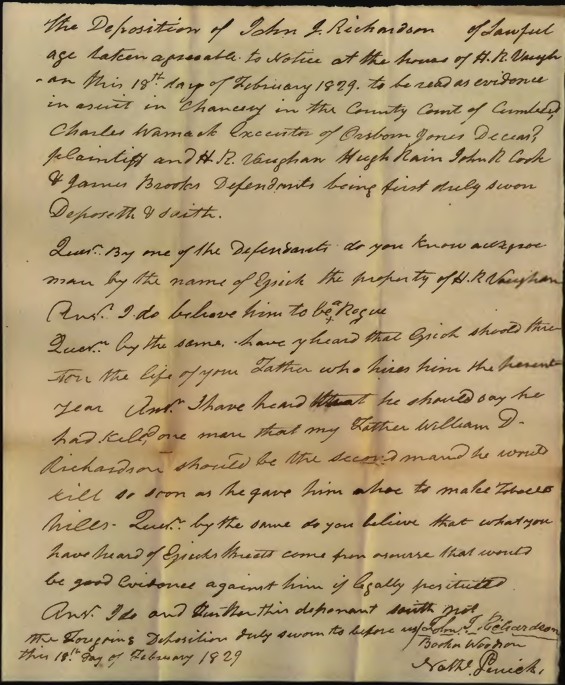

John J. Richardson, questioned by the defense, stated that he knew Essex and believed him “to be a rogue,” and that he had heard Essex claim to have killed one man and to intend that Richardson’s father, who then hired him, would be the second “if he were given a hoe to make tobacco hills.” Richardson affirmed that he believed the source of these reports would be good evidence against Essex.

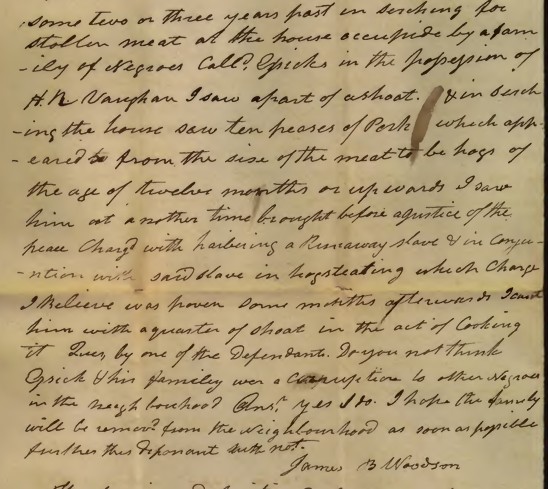

James B. Woodson testified that, two or three years earlier, while searching for stolen meat at the house occupied by “a family of Negroes called Essex’s” in Henrietta’s possession, he saw part of a shoat and ten cuts of pork, apparently from hogs at least twelve months old. He recounted seeing Essex brought before a justice of the peace charged with harboring a runaway slave and stealing hogs with that man—a charge he believed was proven—and said that later he personally caught Essex with a quarter of a shoat (a young hog) in the act of cooking it. When asked whether he thought the family corrupted other enslaved people in the neighborhood, he answered yes and said he hoped they would be removed as soon as possible.

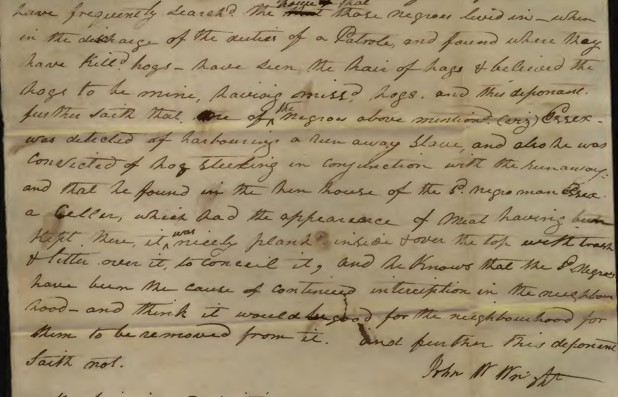

Another patrol, John W. Wright, testified that he had repeatedly searched the house where the family lived and found evidence suggesting they had killed hogs, including hair from hogs he believed were his, as he was missed hogs. He stated that Essex had been detected harboring a runaway slave and convicted of hog stealing with him, and described the cellar in the henhouse where meat appeared to have been kept, “nicely planned inside & over the top with trash and litter over it to conceal it.” He added that these enslaved people had caused “continued interruption in the neighborhood” and that he believed it would be good for the community if they were removed.

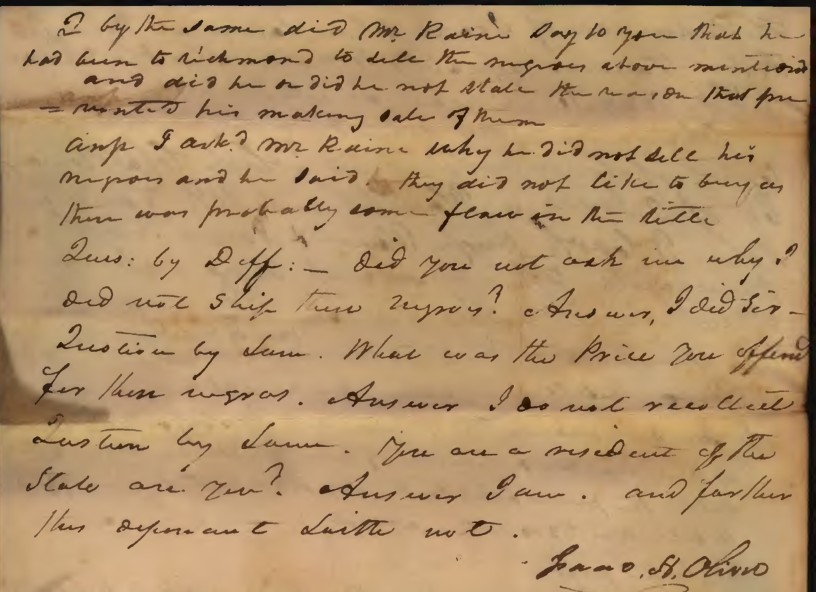

Finally, on 28 February, Isaac Oliver testified that in December 1828 Raine had offered to sell him “one dozen or respect negroes,” about ten to twelve in number, for roughly 2,300 dollars. Oliver confirmed that he was then buying enslaved people to send to New Orleans, that Raine knew this, and that he understood from Foster and others that the enslaved people in question belonged to a lady who intended that they be set free at her death. Oliver recalled Raine telling him that if he did not sell the group to Oliver, he planned to take them to Richmond to sell, and said he later saw Raine returning from Richmond with a group of enslaved people he believed to be the same. When Oliver asked why Raine had not sold them, Raine replied that buyers “did not like to buy, as there was probably some flaw in the title.”

In February 1829, the defendants’ attorney asked the court to take up the case, but the motion was overruled.[16] In March, the parties settled, and the court rescinded the original injunction.[17] The documentary trail then falls largely silent for more than twenty years.

Talk of sending Essex, Sall and their children “to New Orleans, or the South” fit a broader pattern in which sale into the Deep South was itself a punishment and threat deployed against enslaved people deemed troublesome or defiant.

Twenty‑two years stolen

After the 1829 chancery case was settled and the injunction lifted, the record falls silent. On paper, Betsy Jones’s death should have triggered the emancipation clause in Osborne’s will and brought Essex, Sall, and their children into the free Black community in Cumberland. In reality, nothing changed for them. Twenty‑two years of hire meant twenty‑two more years under that same regime of whipping, surveillance, and sale threats.

The next surviving clue appears more than two decades later. On 28 January 1850, the Cumberland County Court ordered that “John Sanders, one of the Executors named in the last Will and testament of Osborne Jones, deceased, be summoned to the next Court to qualify as Executor of the said Osborne Jones decd or to renounce his right.”[18] On 25 February, Sanders appeared and refused to serve, and the court appointed John P. Woodson as administrator de bonis non with the will annexed—a new, court‑appointed administrator to handle what remained of the estate.[19] In January 1851, the court instructed commissioner Hez Ford to examine and settle Woodson’s accounts and report back.[20]

Why, in 1850–51, was Osborne’s estate suddenly active again?

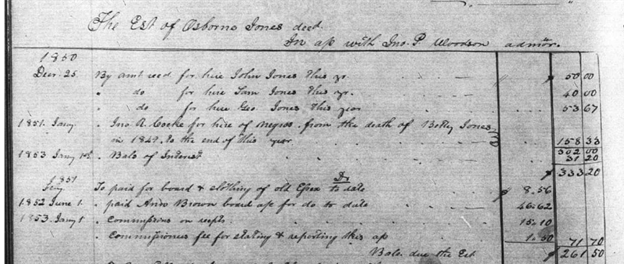

Woodson’s accounting, filed on 1 June 1853, provides the answer.[21] On the revenue side, he recorded a single lump payment of 158.33 dollars from John R. Cooke, Joseph and Henrietta Vaughan’s son‑in‑law, in January 1851 “for hire of negroes from the death of Betsy Jones in 1829 to the end of this year.” That figure represented twenty‑two years of labor at roughly 7.20 dollars per year. It seems as through Cook enjoyed the labor without paying anything until forced to do so. The lump sum payment a retroactive compromise – enough to acknowledge the debt, but not remotely equal to market price over two decades.

Separate entries dated 25 December 1850 list the hire of John Jones for 50 dollars, Sam Jones for 40 dollars, and George Jones for 53.67 dollars “for this year,” presumably 1850. Apart from 341.20 dollars of interest, these hire payments were the only income Woodson reported for the estate.

On the expense side, almost every entry related to one person: the now styled “old” Essex. In February 1851, Woodson paid 8.56 dollars “for board & clothing of old Essex.” On 1 June 1852, he paid Ann Brown 46.62 dollars for Essex’s board. On 1 January 1853, he paid Mrs. Ellis 2 dollars “for board of old Essex for 4 months,” then 13.50 dollars “for clothing for old Essex,” and another 40 dollars to Ann Brown “for board of old Essex from 1 June 1852 to present.” When Woodson presented this account on 27 June 1853, the court ordered it to lie for exceptions until the next term, and on 25 July 1853 it was “ordered to be recorded,” with no exceptions entered on the record.

Charles Womack, the original executor, had never been removed by the court and continued to serve as a justice of the peace and executor for other estates in the years after Betsy’s death. He died in Cumberland County in 1838.[22] The sequence suggests that only when Sam, John, and George forced the question of their freedom in 1851 did the court compel a formal reckoning of what Osborne’s will had actually required from 1829 onward—and of what had been done instead.

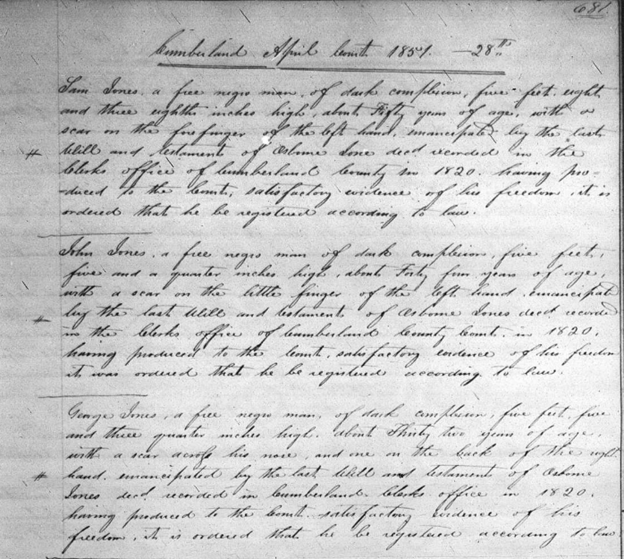

One cent for twenty‑two years

The key to that flurry of mid‑century activity brings us back to where we began. On 26 March 1851, “Sam, John, and George, slaves emancipated by the last Will and testament of Osborne Jones deceased,” filed a petition for leave to sue for their freedom. The court assigned attorney John T. Thornton to represent them and directed that a summons issue against John P. Woodson, administrator de bonis non with the will annexed, requiring him to answer their petition. Woodson appeared by counsel and filed an answer, and a jury was empaneled to decide “whether the said Sam, John and George be free or not.”[23]

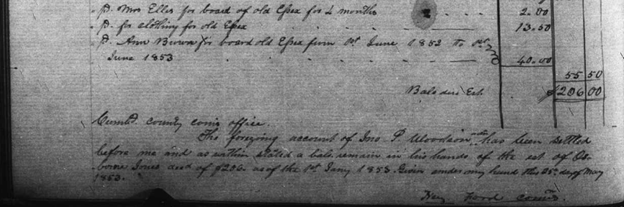

The twelve jurors—Peter B. Foster, William J. Powell, John W. Nash, Philip J. Old, George C. Booker, William M. Cooke, James Banton, Peter Martin, Alexander Mosely, Edward S. Brown, William M. Thornton, and Sterling Cooke—returned three nearly identical verdicts:

“We of the jury find on the issue joined, that the Plaintiff Sam is a free man, and we assess the Plaintiffs damages by reason of his detention at one cent.”

“We of the Jury find on the issue joined, that the plaintiff John is a free man and we assess his damages by reason of his detention at one cent.”

“We the jury find on the issue joined that the Plaintiff George is a free man, and we assess his damages by reason of his detention at one cent.”

The court ordered that Sam, John, and George “recover their freedom,” together with the one‑cent damages and their costs in bringing the suit. After more than two decades in which they were legally entitled to freedom but held in bondage, a Cumberland County jury valued that lost liberty at a penny apiece.

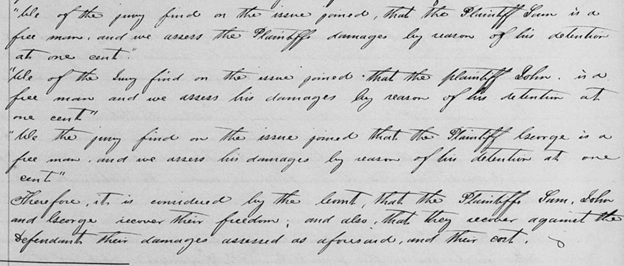

The following month, on 28 April 1851, the court complied with Virginia law by registering each man as a “free negro.” For Sam, the register recorded a free Black man of dark complexion, five feet eight and three‑eighths inches tall, about fifty years of age, with a scar on the forefinger of his left hand, emancipated by Osborne’s will recorded in 1820. For John, it recorded a free Black man of dark complexion, five feet five and one‑quarter inches tall, about forty‑four years old, with a scar on the little finger of his left hand, likewise emancipated by Osborne’s will. For George, it recorded a free Black man of dark complexion, five feet five and three‑quarters inches tall, about thirty‑two years old, with a scar across his nose and another on the back of his right hand, also emancipated by that same instrument. [24] A county list of free Black people dated April 1851 includes all three names.[25]

Freedom with a deadline

Their legal victory started a new clock. Under Virginia law, free Black people were required to leave the state within a year of being emancipated unless they obtained special permission from the General Assembly to remain. Those who stayed without legislative approval risked being sold back into slavery.

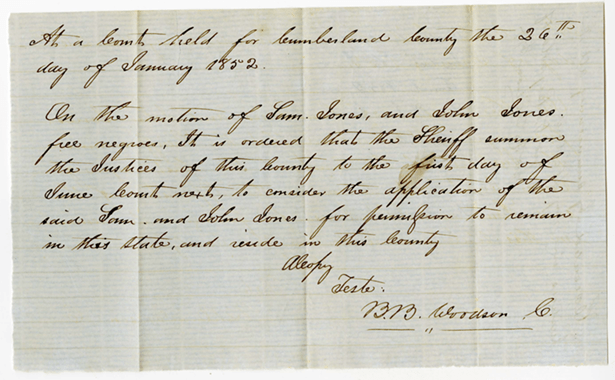

On 26 January 1852, nine months after the jury declared them free, Sam and John petitioned the Cumberland County Court for permission to remain in Virginia. The clerk ordered the sheriff to summon the county justices to consider their application at the June court.[26] No record survives of the county court ever acting on that request or of any petition on their behalf reaching the legislature. George never filed such an application at all.

Essex, Sall, and the cost of delay

The 1853 estate account does not mention Sall by name. Given that she had eight children by 1820, she was likely born about 1780-1785 and appears to have died before the court required Woodson to file the estate account. Essex, probably of similar age, was still alive in the early 1850s – in his 70s, as indicated by the repeated payments for his boarding and clothing styled as “old Essex,” but he does not appear in Cumberland’s free Black registers. It is likely that both Essex and Sall died in bondage, never seeing the legal freedom Osborne had promised them.

How did this family remain enslaved for more than two decades beyond their legal emancipation in 1829? The structure of Osborne’s will created a future interest tied to a life estate, delaying actual freedom until Betsy Jones’s death. Then that interest became tangled in a web of neglected fiduciary duty, procedural inaction, and local white resistance. The record shows not that their freedom was forgotten, but that a combination of legal structure and hostility—including repeated descriptions of the family as “rebellious,” “disobedient,” “rogues,” and “villains,” and accusations that they ran away and threatened white neighbors—kept them in bondage until Sam, John, and George forced the county court to honor the will in 1851.

For Essex and Sall, those extra decades likely meant not only continued enslavement but continued exposure to the whippings, patrol searches, and ever‑present threat of sale that white neighbors invoked when they called them ‘dangerous.’

When they filed their petition, the three men did not arrive with retained counsel: the court appointed John T. Thornton to represent them. Nine months into the twelve‑month period in which they could remain in Virginia without legislative approval, Sam and John asked to stay. The record’s silence speaks volumes. Had the Cumberland Court responded favorably, a petition would be sent to the state legislature – signed by white community member vouching for the petitioner. That did not happen, which suggests they may have left rather than risk being sold again.

George Jones, however, did not leave Virginia so quietly. If you think this story is interesting, you won’t believe what happens next.

Next: The Notorious George Jones

[1] Cumberland County, Virginia Common Law Order Book, 1849-1860, p. 113; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C377-Z3XF-Y?view=explore : Jan 14, 2026), image 87 of 314; Image Group Number: 008574233

[2] Osborne Jones (c.1771-1820) was a son of Thomas Field & Sarah Jones of Amelia County, Virginia. Osborne, Betsey and Patsey Jones are all named in their father’s will dated 12 April 1785 and recorded 26 May 1785 in Amelia County. Amelia County, Virginia. Will Book 4 1786-1793, p. 108; “Amelia, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99P4-XX7Z?view=explore : Jan 8, 2026), image 64 of 160; Image Group Number: 007643927

[3] Turner was paid £3.12. Dr. Philip Turner Southall Account Book 1815-1824, p. 264; “Amelia, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QHV-135T-NX6M?view=explore : Jan 8, 2026), image 136 of 228; Image Group Number: 008961297

[4] Cumberland County, Virginia Will Book 6 1817-1821, p. 259; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89PH-RQ8H?view=explore: Jan 6, 2026), image 138 of 174; Image Group Number: 007644345

[5] Cumberland County, Virginia Will Book 8 1824-1832, p. 18; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89PH-R31G?view=explore: Jan 7, 2026), image 18 of 320; Image Group Number: 007644345

[6] Zaborney, John. The Domestic Slave Trade in Virginia. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/slave-sales.

[7] 1860. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2002698281/.

[8] William Lee & Eliza C. Womack, m.b. 6 December 1823, Surety Benj. Holeman, Test: Charles Womack, Jr., Note: dau of Chas. Womack. Elliott, Katherine B., Marriage Records, 1749-1840, Cumberland County, Virginia, (South Hill, VA: self-published, 1969), p. 80

[9] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1824-1826, p. 260; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-79FJ-1?view=explore : Jan 10, 2026), image 149 of 347; Image Group Number: 008358487

[10] Joseph Vaughan will dated 11 July 1823 and recorded 25 July 1825. Cumberland County, Virginia Will Book 8 1824-1832, p. 105; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89PH-R7J7?view=explore : Jan 17, 2026), image 61 of 320; Image Group Number: 007644345

[11] Nicholls, Michael. Gabriel’s Conspiracy (1800). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/gabriels-conspiracy-1800.

[12] Breen, Patrick. Nat Turner’s Revolt (1831). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/turners-revolt-nat-1831.

[13] Root, Erik. Virginia Slavery Debate of 1831–1832, The. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/virginia-slavery-debate-of-1831-1832-the.

[14] Cumberland County, Virginia, Chancery Index Number: 1829-009, Exor of Osborne Jones v. Henrietta R Vaughan, Etc., Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections, Chancery Records Index; https://old.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/default.asp#res

[15] Virginia Writers’ Project. Chapter 15: “Thirty and Nine”; an excerpt from The Negro in Virginia (1940). (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/primary-documents/chapter-15-thirty-and-nine-an-excerpt-from-the-negro-in-virginia-1940.

[16] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1827-1829, p. 434; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSRP-M71T-B?view=explore: Jan 7, 2026), image 25 of 67; Image Group Number: 008312820

[17] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1827-1829, p. 253; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSRP-MWM9-B?view=explore : Jan 7, 2026), image 33 of 67; Image Group Number: 008312820

[18] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1844-1851, p. 556; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-M77K-9?view=explore : Jan 14, 2026), image 306 of 336; Image Group Number: 008358489

[19] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1844-1851, p. 563; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-M77V-Z?view=explore : Jan 17, 2026), image 309 of 336; Image Group Number: 008358489

[20] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1844-1851, p. 643; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-M77V-9?view=explore: Jan 14, 2026), image 30 of 55; Image Group Number: 008358489

[21] Cumberland County, Virginia Will Book 12 1852-1860, p. 108; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99PH-R3DX?view=explore : Jan 6, 2026), image 71 of 359; Image Group Number: 007644347

[22] Cumberland County Virginia Will Book 10, 1837-1844, p. 95; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9PC-MG1?view=explore : Jan 17, 2026), image 53 of 230; Image Group Number: 007644346

[23] Cumberland County, Virginia Common Law Order Book, 1849-1860, p. 113; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C377-Z3XF-Y?view=explore : Jan 14, 2026), image 87 of 314; Image Group Number: 008574233

[24] Cumberland County, Virginia Order Book 1844-1851, p. 681; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-M77X-6?view=explore : Jan 6, 2026), image 49 of 55; Image Group Number: 008358489

[25] List of Free Negroes Registered [1852-1854, 1856-1857], 1857 (1156166_0006_0007). Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative Digital Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Va.

[26] Cumberland County Virginia Order Book 1851-1857, p. 50; “Cumberland, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-M77H-Y?view=explore : Jan 14, 2026), image 52 of 343; Image Group Number: 008358489

[27] Jones, Samuel : Petition to Remain in the Commonwealth, Cumberland County (Va.) Free Negro and Slave Records, 1753-1865 , Virginia Untold: The African American Narrative, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://lva.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/permalink/01LVA_INST/br4o1h/alma9917832401105756

Nice cliffhanger ending!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for taking the time to read it John. Need to give you a call – re: Clarke.

LikeLike

Steve, this is an amazing, and important story! I

LikeLike

Thanks so much for reading it – and writing! It’s really unbelievable. Just wait for part 2 – it’s even more incredible.

LikeLike

I did read the artic

LikeLike