Virginia Chancery Court records are an invaluable resource for genealogists. But once in a while, they do more than confirm dates — they unlock secrets. That’s exactly what happened when I stumbled upon an 1805 court case involving the family of my 7x great-grandfather Richard Gray of Lawnes Creek Parish in Surry County, Virginia.

A Will Divides More than Property

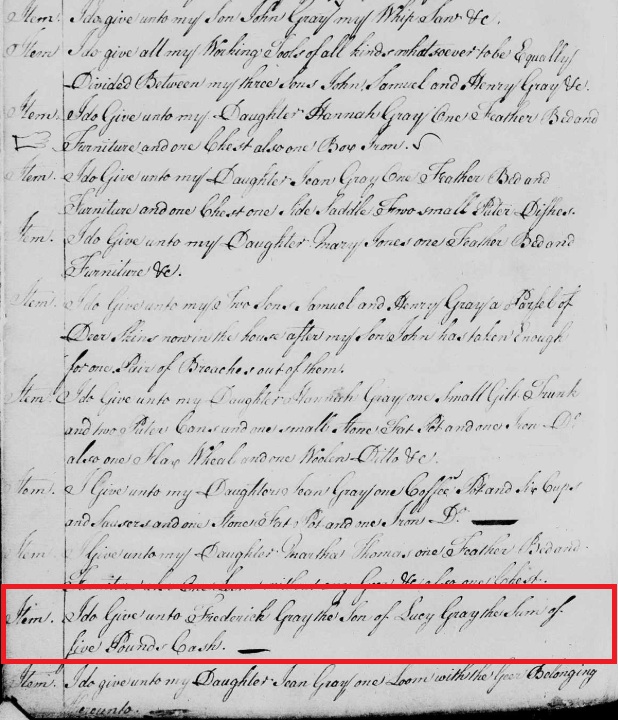

“In the Name of God Amen April the 7th 1777. I Richard Gray of Surry County being sick and weak in body but of perfect memory and sense Thanks be to Almighty God for the same and showing that it is Appointed for all men once to Die do make constitute and Ordain this to be my Last Will and Testament.”

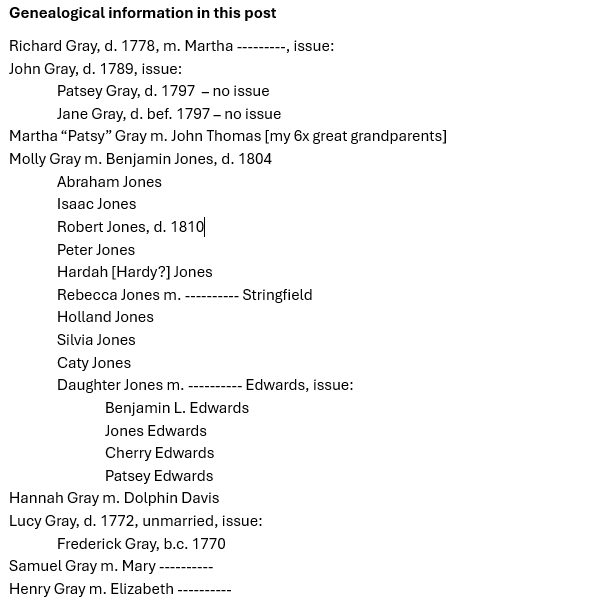

And so began the last will and testament of my 7x great grandfather. He went on to make generous bequests to his children including sons John Gray, Samuel Gray and Henry Gray – and his daughters Hannah Gray, Jane Gray, Mary Jones and Martha Thomas. One name in the will stands out – Frederick Gray, the son of Lucy Gray, to whom Richard Gray left £5.[1] While he calls each of the others son or daughter, husband of, etc., Richard Gray doe does not state his relationship to Frederick Gray or to Lucy Gray. That would soon be remedied.

The Chancery Suit

In May 1805, Frederick Gray filed a suit in the Surry County Chancery Court in which he describes himself as the “natural son” of Lucy Gray. She died in 1772 and was daughter of Richard Gray. [2] Mystery solved!

The defendants included his maternal aunts and uncles. At issue was a 200 acre tract of land in Lawnes Creek Parish in Surry County that Richard Gray had willed in 1777 to his son John Gray. When John Gray died in 1789, the land fell to his daughters Patsey Gray and Jean Gray. Neither married nor had children so when Patsey, the last of them, died in 1797, the property fell to her paternal statutory heirs – John and Lucy Gray’s surviving siblings. Frederick Gray wanted his mother’s rightful share and they did not want to give it to him.

A Divided Property Restored

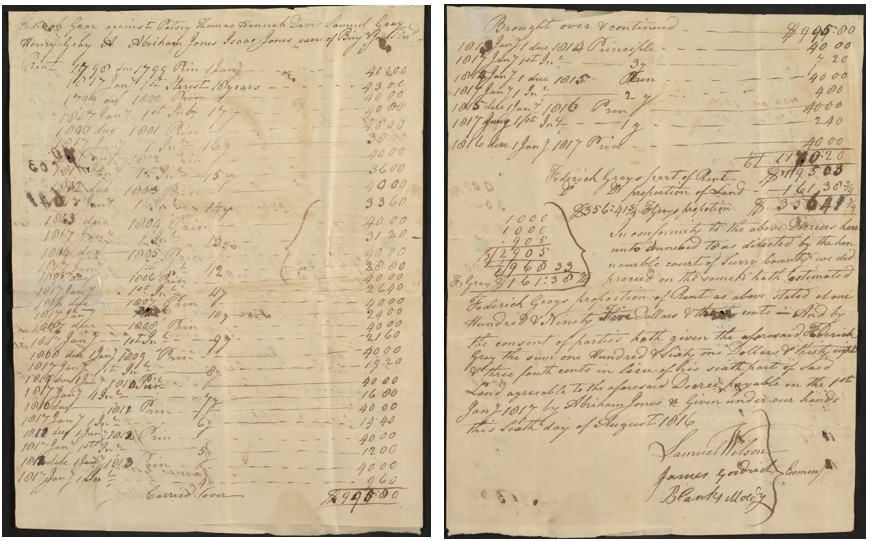

By time Frederick Gray filed his 1805 suit, his uncle and aunt Benjamin and Mary (Gray) Jones had bought out some of the other heirs. In 1798, they purchased the interests of Dolphin & Hannah (Gray) Davis and Henry Gray & wife Elizabeth[3] and in 1801 he bought out John and Martha (Gray) Thomas.[4] Then on 9 March 1804, Benjamin Jones of Isle of Wight County sold the 166 2/3 acres to his son Abraham Jones.[5]

Interestingly, Benjamin Jones had made his will a few weeks prior on 19 February 1804 bequeathing to son Abraham “all my right, title, claim, interest and demand to a certain tract or parcel of land whereon he now lives containing by estimation 200 acres.” Surprisingly, Frederick Gray was one of the witnesses. !he will was recorded in Isle of Wight County on19 February 1805.[6]

The last Gray sibling to still retain his interest in was Samuel Gray who with wife Mary sold it on 8 February 1805 to their nephew Abraham Jones.[7] For the first time since 1789, the land was all owned by one person. Or so they thought.

A Natural Born Son Asserts His Rights

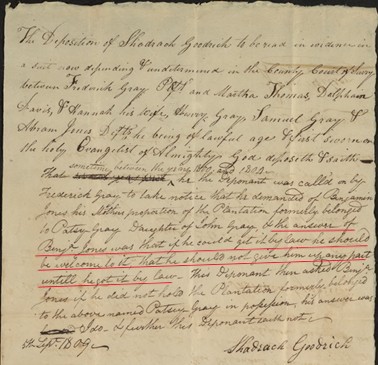

During the suit, several witnesses were deposed. Shadrack Goodrich testified that when Fredrick Gray demanded that Benjamin Jones give him his mother’s portion, Jones said, “if he can get it by law he should be welcome to it,” and “that he should not give it to him up any part until he got it by law.” These words, both a rebuff and a challenge, set the tone for a protracted legal battle that would stretch over a dozen years.

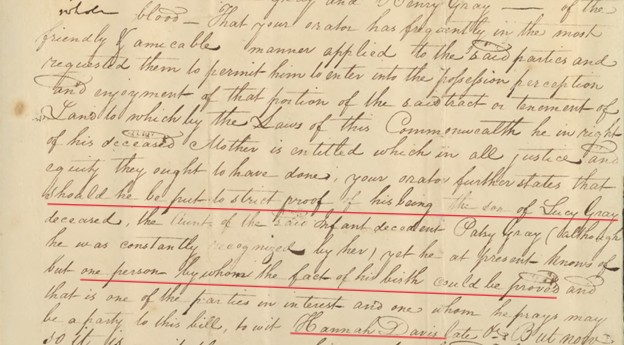

Frederick Gray told the court that he had asked for his mother’s share and been refused. He added that “should he be put to strict proof of his being the son of Lucy Gray deceased . . . he at present knows of but one person by whom the fact of his birth could be proved and that is one of the parties at interest and one whom prays he may be a party to this bill, to wit: Hannah Davis, late Hannah Gray.”

Frederick Gray then accused his uncles and aunts of “combining and confederating themselves together & to and with one Abram Jones,” who was in possession of the land “have utterly refused to comply with his request.”

The Gray Siblings Respond to the Suit

Less than a year later, on 20 January 1806, Abraham & Nancy Jones had moved to adjacent Isle of Wight County when they sold the 200-acre tract to his brother Robert Jones.[8] This sale from Abraham to Robert took place several months after Frederick Gray filed suit.

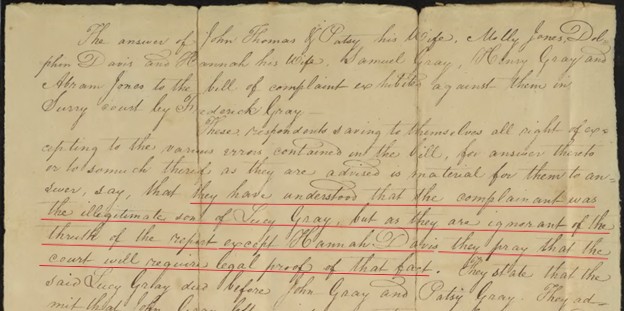

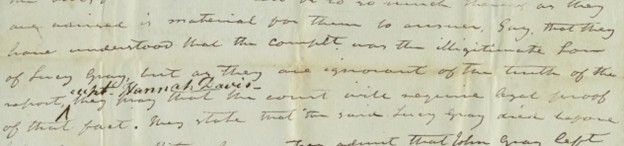

Nearly six months after the sale, on 12 July 1806, the siblings filed their response to Frederick Gray’s suit. They stated that “. . . they have understood that the complainant was the illegitimate son of Lucy Gray, but as they are ignorant of the truth of the report except Hannah Davis they pray that the court will require legal proof of that fact.”

Interestingly, a draft of the siblings response is included in the file and the words “except Hannah Davis” were added after the draft was prepared.

Aunt Hannah’s Tells the Truth

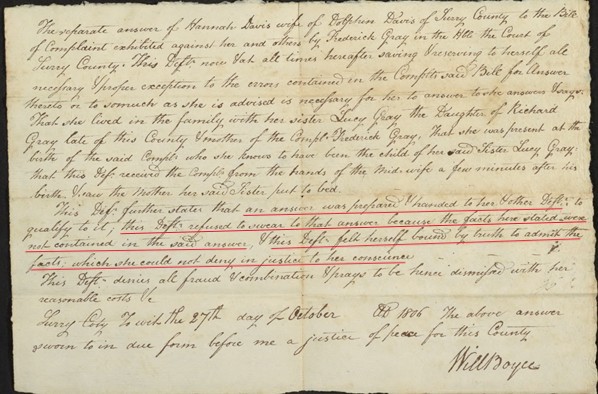

On 27 October 1806, the reason for the change becomes apparent when Hannah (Gray) Davis files her own response, which states “That she lived in the family of her sister Lucy Gray, the daughter of Richard Gray late of this County and mother of the Complainant Frederick Gray. That she was present at the birth of said Complainant, who she knows to have been the child of her sister Lucy Gray. That this Deft received the Compl from the hands of the midwife a few minutes after his birth & saw the mother her said sister put to bed.” Indeed, Aunt Hannah could “legally” prove his relationship to Lucy Gray.

But Aunt Hannah had more to say:

This Deft further states that an answer was prepared and handed to her & other Defts to qualify to it; this Deft refused to swear to that answer because the facts here stated were not contained in the said answer, & this Deft felt herself bound by truth to admit the facts; which she could not deny in justice to her conscience.”

More Witnesses Strengthen the Case

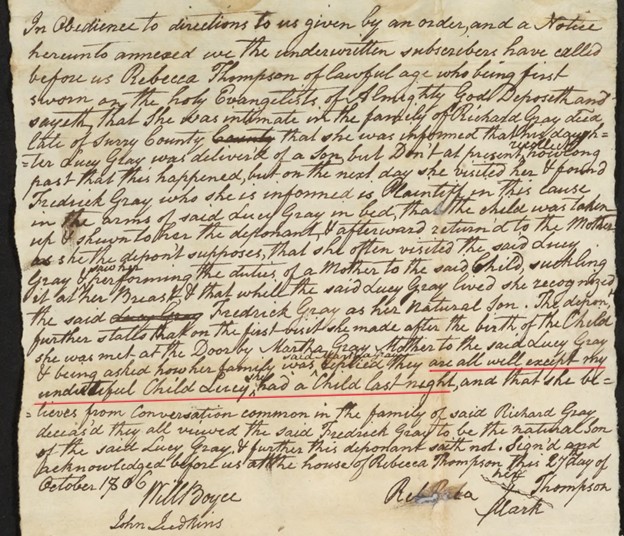

Neighbor Rebecca Thompson, widow of John Thompson, was also deposed. She testified that “she was intimate in the family of Richard Gray and that she was informed that Lucy Gray was delivered of a son, but don’t at present recollect how long past this happened, but on the next day she visited her & found Frederick Gray who she is informed is Plaintiff in this cause in the arms of said Lucy Gray in bed.”

Thompson continued “She often visited the said Lucy Gray and that she performed the duties of a mother to the said child suckling it at her breast, that while the said Lucy Gray lived she recognized the said Frederick Gray as her natural son.” She added that on the first visit she asked Lucy’s mother Martha Gray how her family was and she replied, “they all are well except my undutiful child Lucy, she had a child last night.”

Samuel Millington was also deposed and said that everything Rebecca Thompson had said was true “and he has only to add that he lived in the same family as the said Lucy Gray and went with John Thomas for the midwife” and saw the child the next day “owned by Lucy Gray as her son” and “who continued to do so until her death.”

The Court’s Decree

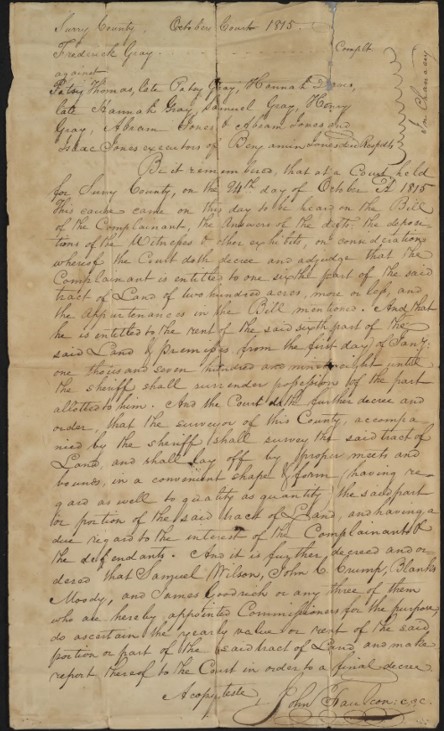

After more than a decade, on 21 October 1815, the Surry Court decreed that Fredrick Gray was entitled to a 1/6 part of the land as well as 1/6 part of rental income from leasing the land from 1 January 1798 (Patsey Gray died in 1797).

The following year the Court issued an amended decree that he commissioners previously appointed, assign by allotment [by draw] to the complainant one equal sixth part of the said land and one equal part of the rents of the whole land and make report to this court.

Frederick Gray Becomes a landowner

What did Frederick do with his land? He sold it. Perhaps a little surprising since he had fought for so long for it and did not own any other land. He was a tenant farmer leasing a farm called Chestnut Hill from Thomas R Blow from 1800-1805[9] and leased an 1,158-acre farm “Holt’s orphans” which he held at the time of this death.[10]

Robert Jones had died in 1810 during the case.[11] The land fell to his daughters. In a deed dated 26 August 1816, Frederick Gray sold to Amanda Jones and Nancy Robert Jones for $161.38 and ¾ cents, 30 1/6 acres adjoining Samuel Wilson, Richard Thomas, and the White Marsh tract, it being 1/6 of the tract of land which Robert Jones his life time purchased of Abram Jones, and which said 1/6 the said Frederick Gray recovered of Patsy Thomas, late Patsy Gray, Hannah Davis late Hannah Gray, Samuel Gray, Henry Gray, Abram Jones and Abram and Isaac Jones, Executors of Benjamin Jones, decd. as per a decree pronounced by the County Court of Surry at October Court 1815.[12] This gave the daughters of Robert Jones 100 percent ownership of the 200 acres.

There is a little more to the story . . .

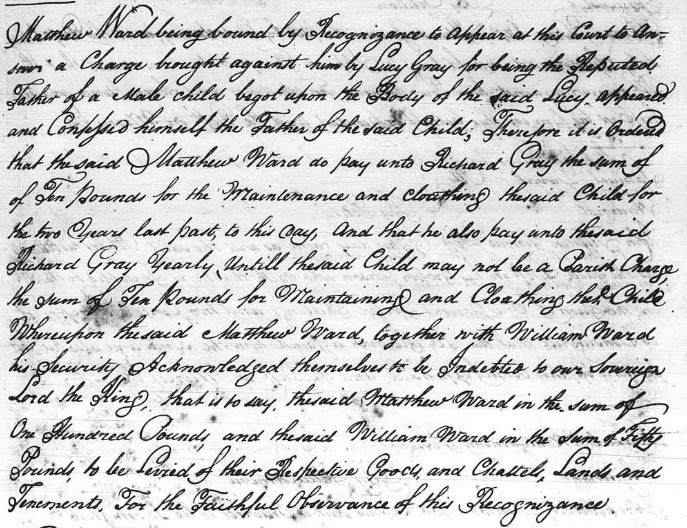

On 21 January 1773, Matthew Ward appeared before the Surry Court to answer a charge brought by Lucy Gray “for being the reputed father of a male child begot upon the body of the said Lucy.” Ward “appeared and confessed himself the father of the child.” The court ordered him to pay Richard Gray £10 per year for the “maintenance and clothing the said child the two years last part to this day,” and that he also pay Richard Gray £10 annually so the child would not be a parish charge. Matthew Ward acknowledged his bond of £100 and his security William Ward acknowledged his bond of £50.[13] This record suggests that Frederick Gray was born in late 1770 or early 1771.

Matthew Ward moved to Amelia County in 1774 as a witness to a deed.[14] Then on 27 April 1774 the Surry County Court ordered Matthias Marriott to pay Matthew Ward for 12 days attendance and returning 92 miles as a witness for him.[15] Ninety-two miles could easily take one from Amelia County to Surry County Court House. Matthew Ward lived in the portion of Amelia that became Nottoway County in 1789. He died intestate and his inventory and appraisal, taken on 2 December 1803, was recorded on 9 June 1804.[16] He left a wife Rhoda, d.c. 1809, and four children Robert Ward, Benjamin Ward, Elizabeth Ward and Nathan Ward.[17]

And still a little more . . .

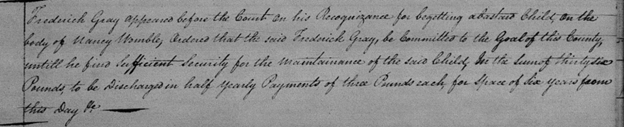

On 2 February 1796, Frederick Gray appeared before the Isle of Wight County Court for “begetting a bastard Child, on the body of Nancy Womble.” The court ordered that Frederick Gray be jailed until he found sufficient security for the maintenance of the child. The court required him to pay £36 in half yearly payments of three pounds each for space of six years from this day &c.[18]

Frederick Gray made his will in Surry County on 8 June 1820. He named his son Byrd Gray, his “relation” Karen Mangum, son Peyton Gray, daughter Elizabeth Ellensworth and daughter Lucy Gray. Son-in-law Benjamin W Ellensworth was named executor. The will was recorded on 24 October 1820.[19] As his wife is not mentioned, she was already dead. I have been unable to identify her.

The Truth Will Win Out

Sometimes the records reveal stories about a family that are not particularly flattering. It seems evident that Lucy Gray’s siblings knew Frederick Gray was her son. They all lived on either side of Lawnes Creek Surry County or Isle of Wight County. They must have known about Matthew Ward confessing he was Frederick’s father. Were Lucy’s father and brothers not with her at court? Or was she made to face that alone? In either case, they would have known about it.

John Thomas [my 6x great grandfather] went to get the midwife for Lucy. Richard Thomas’ 1777 will called him the son of Lucy Gray. While Lucy’s sister Hannah (Gray) Davis was present at the birth, the others who all lived close by undoubtedly saw him as a baby and regularly throughout his childhood. They essentially conceded it was true in their answer, but demanded “legal” proof. Frederick’s allegation of them conspiring and confederating together seems credible.

Why Did They Do it?

Was it as simple as greed? Benjamin and Abraham Jones paid £144 to the Gray siblings for their portions. When Robert Jones bought the whole 200 acres in 1806 he paid £240. Frederick’s 1/6 share of the land plus his 1/6 share of rent from 1798-1815 amounted to $356 or about £80. Yes, they used both dollars and pounds simultaneously for a while in the early United States; sometimes both may appear in the same document.

Perhaps it also had to do with the circumstance of Frederick Gray’ birth. In fact, it may explain his grandfather’s modest £5 bequest in his will. Had Lucy Gray been alive when her father made his will, would she have received the featherbeds, chests, tables and pewter plates he left his other daughters?

During this time period, having a child outside of marriage carried all sorts of negative economic, legal, social and religious implications. In 1769, the state legislature passed a law “to provide for the security and indemnifying the parishes from the great charges frequently arising from children begotten and born out of lawful matrimony,” which was aimed holding father’s accountable.[20]

From Matthew Ward’s [1772] and Frederick Gray’s [1796] appearances before county courts as fathers of such children, we can see that the courts and the Overseers of the Poor [successors to pre Revolution churchwardens or vestry men] were especially concerned about the child becoming a financial burden on the community. As was the case when Frederick Gray appeared in court, the child was usually not named and referred to as a “bastard.”

Undoubtedly, the broader community often stigmatized unwed mothers and their children – including the church. Immediate and extended family were probably ashamed and certainly were caught between social convention and any familial feelings about the child. They also had their own children for which they wanted to provide. The day after Frederick Gray was born, a visitor mentioned that Lucy’s own mother had called her an “undutiful child.”

Frederick became more vulnerable when his mother died. He was not bound out as an apprentice and he as literate suggesting his relatives took him in. After his mother’s death, Frederick Gray probably remained in Richard Gray’s home where he had been born and his mother died. He probably remained with his grandparents and unmarried aunts – at least until his grandfather died in 1778. He may have remained there with his Uncle John Gray, who inherited the property. In fact, Frederick was living John Gray in 1788.[21] I found no guardian appointment for him, but of course he had no estate that required such attention.

In the end, Frederick Gray received some measure of justice from the Surry Court, but we are left to wonder how he felt about it all. Aside from anger and frustration, he must have been deeply saddened to be part of a family that did not – or perhaps could not – fully accept him.

[1] Surry County, Virginia Will, Etc. 10, 1768-1779, p. 516; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-K326?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 269 of 275; Image Group Number: 007645826

[2] Frederick Gray vs. John Thomas & wife, etal. Surry County Virginia Chancery Court, Virginia Chancery Records, Index Number 1817-005, Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://old.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=181-1817-005

[3] Surry County Virginia Deed Book 1, 1792-1799, p. 1 , p. 656; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-HSJM?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 353 of 391; Image Group Number: 008562838

[4] Surry County Virginia Deed Book 2, 1799-1804, p. 159; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-HSKY?view=explore : Jul 22, 2025), image 88 of 277; Image Group Number: 008562838

[5] Surry County Virginia Deed Book 3, 1801-1804, p. 1; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-ZSB1-X?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 13 of 333; Image Group Number: 008562839

[6] Isle of Wight County Virginia Will Book 12, 1804-1808, p. 86; “Isle of Wight, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9P6-539S?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 54 of 237; Image Group Number: 007645163

[7] Surry County Virginia Deed Book 3, 1804-1811, p. 31; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-Z3M2-X?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 28 of 333; Image Group Number: 008562839

[8] Surry County Virginia Deede Book 3, 1804-1811, p. 121; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-ZSRF-6?view=explore : Jul 21, 2025), image 75 of 333; Image Group Number: 008562839

[9] Surry County Deed Book 2, 1799-1804, p. 47; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-H3KT?view=explore : Jul 24, 2025), image 32 of 277; Image Group Number: 008562838

[10] Surry County Virginia Land Estate Tax Records 1821; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-996N-CX6V?view=explore : Jul 24, 2025), image 10 of 18; Image Group Number: 004124833

[11] Surry County Virginia Wills, Etc., 2, 1804-1815, p. 538; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-K497?view=explore : Jul 21, 2025), image 281 of 322; Image Group Number: 007645831

[12] Surry County Virginia Deed Book 5, 1815-1818, p. 278; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C3QP-66H?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 165 of 298; Image Group Number: 008562840

[13] Surry County Virginia Order Book, 1764-1774, p. 281; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-6L25?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 169 of 260; Image Group Number: 008359685

[14] Amelia County, Virginia Deed Book 13, 1774-1776, p. 118; “Amelia, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-LS9T-5?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 65 of 113; Image Group Number: 008358439

[15] Surry County Virginia Order Book, 1764-1774, p. 447; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-6LH7?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 252 of 260; Image Group Number: 008359685

[16] Nottoway County, Virginia Will Book 2, 1803-1809, p. 86; “Nottoway, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99PX-64FQ?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 68 of 296; Image Group Number: 007645687

[17] Nottoway County, Virginia Order Book 5, 1806-1809, p.

[18] Isle of Wight County Virginia Order Book, 1795-1797, p. 279; “Isle of Wight, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSY6-B9BR-B?view=explore : Jul 20, 2025), image 176 of 309; Image Group Number: 008359383

[19] Surry County Virginia Wills, Etc., 3, 1815-1821, p. 477; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KWH9?view=explore : Jul 21, 2025), image 258 of 296; Image Group Number: 007645831

[20] Dominik Lasok, Virginia Bastardy Laws: A Burdensome Heritage, 9 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 402

(1967), p. 419; https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol9/iss2/8

[21] Surry County Virginia Personal Property Taxes, 1788; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C37H-H3V4-G?view=explore : Jul 24, 2025), image 11 of 29; Image Group Number: 008574973

One honest person

LikeLike