If you missed my earlier post My Blanton Family Roots, which is about my 7x great grandfather Thomas Blanton I of Old Rappahannock County and Essex County, Virginia, you can check it out here:

For sons Thomas Blanton II and John Blanton see My Blanton Family Roots – Part 2 – The Second Generation here: https://asonofvirginia.blog/2025/04/07/my-blanton-family-root-part-2-the-second-generation/.

Richard Blanton I of Spotsylvania County (c.1688-c.1734) – carpenter

Richard2 Blanton I, son of Thomas and Jane (———-) Blanton, was probably born about 1686-1690 in the southern half of (Old) Rappahannock County, which became Essex County in 1692. When his father, Thomas Blanton, made his will on 7 February 1697/8, he made a bequest to his four sons: Thomas and John & William & Richard Blanton, all my land it to be equally divided unto them and if either of them shall die before he shall come of age then his part shall come to the others and so in case of them all & my Son, Richard Blanton shall have my plantation in his part.”

Richard Blanton was to receive his father’s “plantation in his part” referring to the part of the land on which Thomas Blanton I’s house and various outbuildings were located. The youngest son often received that portion as older brothers would receive their portions as they came of age and started their own lives.[1] Their father owned to three contiguous tracts totaling 666 acres [two tracts by grant and one by deed – see Part 1].

After being mentioned in their father’s will, Richard Blanton and his brother William Blanton next appear in the record on 19 May 1719, when they were described as “of St. Mary’s Parish in the County of Essex, planters.” They sold Daniel Sullivant 94 acres [47 x 2] for £18.6. The land was in South Farnham Parish in Essex County and is described as part of larger tract patented by Major Robert Beverely on 21 September 1674.[2] Also in 1719, brother John Blanton sold his 47 acre portion to Richard Hill.[3] Finally, in 1724, brother Thomas Blanton and wife Ann sold his 47 portion to Jane Hill and her son John Hill.[4] These combined 188 acres were the brothers’ share of the 200 acre +/- tract Thomas Blanton I bought from Robert Beverely’s son Harry Beverly in 1695.[5]

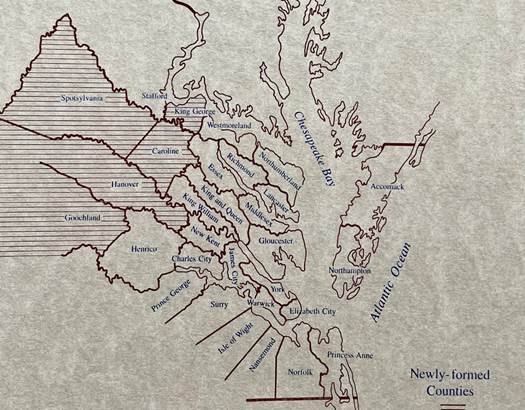

A New County and New Opportunities

Spotsylvania County was created out of portions of Essex, King & Queen and King William Counties in 1720 and became effective in 1721. Richard Blanton is first mentioned in the Spotsylvania record as living adjacent to a tract being sold in a deed dated 2 November 1722 from Larkin Chew to John Landrum. The only waterway mentioned is Green’s Branch.[6] He appeared as a witness on for Richard Cheek in his suit against Benjmain Robinson and 1 June 1725 was allowed [paid] for four days attendance.[7] On 2 May 1727 he was allowed two days attendance at 40 lbs of tobacco per day as he had been summoned as a witness by John Hullock v. John Pridgen.[8] On 5 March 1727/8, Robert King, Richard Blanton, John Foster, Thomas Graves or any three of them, were ordered to appraise the estate of William Dalton.[9]

On 1 October 1728 Richard Blanton was among several men who received a bounty for a wolf’s head.[10] Early Virginia records are filled with references to bounties being paid for wolves heads. Colonists undoubtedly considered them a threat to both livestock and game animals they hunted. Religion played a part as well, colonists believing wolves to be a literal threat to their spiritual well-being and capable of murdering their souls. The New Testament contains numerous negative references to wolves, usually in metaphors or parables that also mention sheep.[11]

Digression: I do not normally tout a footnote, but Vallerie Fogleman’s American Attitudes Towards Wolves: A History of Misperception, is a particularly good read. To access it you need free JSTOR subscription (independent researchers can “view only” up to 100 articles per month). JSTOR is a go to resource for historians and genealogists – or should be! Article Link: https://www.jstor.org/stable/3984536

On 28 October 1729 Richard Blanton’s suit against Lazarus Tilly for trespass was dismissed[12] and on 3 November 1730 Richard Blanton served on grand jury.[13] On 3 April 1733 Rice Curtis, Richard Blanton, Francis Smith, John Durrett, or any three of them to appraise the estate of John Small.[14]

Granted Land Must be Seated

When land patents were issued, they came with a requirement to “seat’ the tract by building buildings, improving the land and turning it into a farm within three years. Failure to do so could result in the tract being regranted to someone else. Richard Blanton, a carpenter, was called upon to “view the building works and improvements” of various patentees. On 1 March 1725/6, William Bartlett and Richard Blanton returned their report of the valuation of building works and improvements of Coll. Gawen Corbett’s tracts.[15] On 1 November 1726, Richard Blanton and William Blanton were among the men appointed to view building works and improvements of Ambrose Madison and Thomas Chew’s patented and now seated land.[16] On 1 April 1729, Richard Blanton was among the men appointed to view the building works & improvements of Thomas and Larkin Chew’s patented land.[17] On 3 March 1729/30, Richard Blanton among several men, any two of them to view the building works and improvements of two patented tracts belonging to Thomas Chew and Thomas and Larkin Chew.[18] Finally, on 3 June 1729, Richard Blanton, John Bush, John Durrett, or any two of them, were appointed to view the building works & improvements of Michael Guinney.[19] On 1 July 1729 – Michael Guinney returned Richard Blanton and John Durrett’s report.[20]

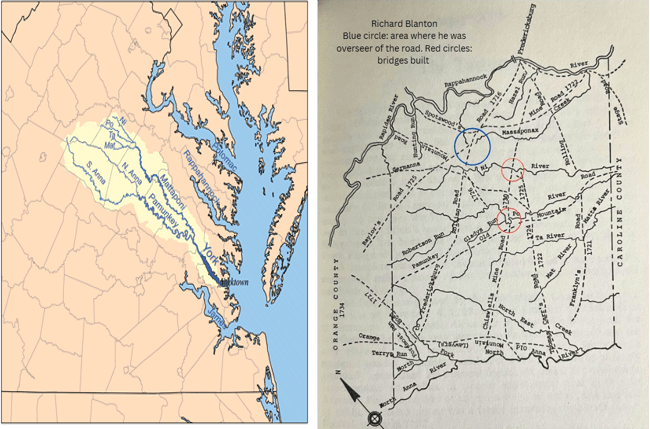

New Roads Built and Maintained

A new county needed roads including rolling roads for moving tobacco in casks, as well as bridle paths and cart roads. Building and maintaining these various roads was done by local residents and their enslaved laborers. On 1 April 1729, Richard Blanton was appointed overseer in place of his brother John Blanton for the rolling road from Nassaponax [Massaponax] Road to the Mattapony main road.[21] The following year on 7 April 1730, William Bartlett, overseer of the Mine Road, Vizt: from the ridge between Pamunkey and Mattapony to the river Ny petitioned to be discharged as he had “laid out and marked per the viewers appointed.” Richard Blanton was appointed to take Bartlett’s place and the court ordered that all male laboring tithables within four miles of each side of the said road were to help him make the road clear and keep it in good repair.[22] After taking his oath, on 5 May 1730, the court appointed Richard Blanton overseer of the Mine Road in the room of William Bartlett.[23]

Building Bridges

Bridge building was an important part of infrastructure development especially as settlement expanded and people needed reliable crossings over rivers and streams. Valuing the timber, which was to be paid for using public funds, was a critical first step. On 8 August 1728, Wiliam Johnson and Robert King petitioned to have men appointed to view and value the timber necessary to build a bridge over the river Po. The court appointed Richard Blanton and Anthony Foster to make a report and return it to the next court.[24] They did so on 4 September 1728, which the court ordered recorded.[25]

On 7 July 1730 John Wigglesworth and Richard Blanton gave bond for keeping the Mine Bridge that Wigglesworth built and finished over the River Po in good repair for seven years according to an agreement made with Charles Chiswell.[26] On 3 March 1730/1, Daniel Browne, Richard Blanton, William Barlett, and John Wigglesworth, or any three of them, were appointed to value the timber for building a bridge over the River Po in the Mine Road, but they failed to handle it and the court ordered Joseph Brock and John Waller, Gentlemen, to value the same and make a report.[27]

On 4 May 1731, the court ordered “Richard Blanton and his gang do put the bridge over Lewis’ River [the Ni River] in the Mine Road forthwith in good repair.”[28] Perhaps he had not done so when on 13 November 1731, the court ordered that John Grayson and Richard Blanton with their gangs, “do forthwith put the bridge over the River and in the Mine Road in good repair.”[29]

Granted Land Must be Seated

When land patents were issued, they came with a requirement to “seat’ the tract by building buildings, improving the land and turning it into a farm within three years. Failure to do so could result in the tract being regranted to someone else. Richard Blanton was called upon to “view the building works and improvements” of various patentees. On 1 March 1725/6, William Bartlett and Richard Blanton returned their report of the valuation of building works and improvements of Coll. Gawen Corbett’s tracts.[30] On 1 November 1726, Richard Blanton and William Blanton were among the men appointed to view building works and improvements of Ambrose Madison and Thomas Chew’s patented and now seated land.[31] On 1 April 1729, Richard Blanton was among the men appointed to view the building works & improvements of Thomas and Larkin Chew’s patented land.[32] On 3 March 1729/30, Richard Blanton among several men, any two of them to view the building works and improvements of two patented tracts belonging to Thomas Chew and Thomas and Larkin Chew.[33] Finally, on 3 June 1729, Richard Blanton, John Bush, John Durrett, or any two of them, were appointed to view the building works & improvements of Michael Guinney.[34] On 1 July 1729 – Michael Guinney returned Richard Blanton and John Durrett’s report.[35]

Death of Richard Blanton

He may still been alive on 4 July 1733, when the court dismissed an attachment of goods “obtained by Richard Blanton against the estate of William Mack for £4,” however, the “said Blanton failed to appear” so we cannot be sure.[36] Richard Blanton was dead by 3 September 1734 when his widow Elizabeth Blanton presented his will at court. That record reveals that his son Richard II, one of his executors, was not old enough to serve so administration of the estate was granted to his widow and co-executor, Elizabeth Blanton.[37] Richard Blanton I was probably in his mid 40s when he died.

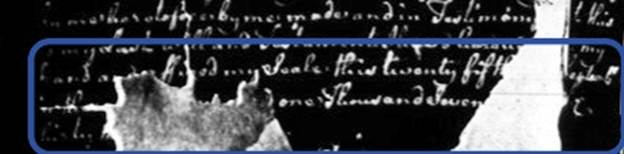

Fortunately, Richard Blanton I’s willis extant. Unfortunately, it is badly fragmented and difficult to read.[38] In particular, the will date is not readable. Or is it?

Below is my transcription of the date portion of the will. I have added the missing words in [brackets] considering typical will wording as well as letter and word spacing. Nothing scientific here – just for fun!

“ . . . my Seale this twenty fifth [day of] [A]prill

in the [year of our Lor]d one Thousand Seven [hundred] &

thirty t [either “wo” 1732 or “hree” 1733].

The most challenging part is the year. Thirty is faded but visible another word follows – the first letter of which is just partially visible. You can see it’s not an “o” for “one” so 1731 is out. I do not see anything dangling so it’s not an “f” eliminating “four” or 1734. That leaves “t” and based on what is visible I cannot eliminate “tw” or “th” so I say it’s either 1732 or 1733. Now you try it – and let me what you think.

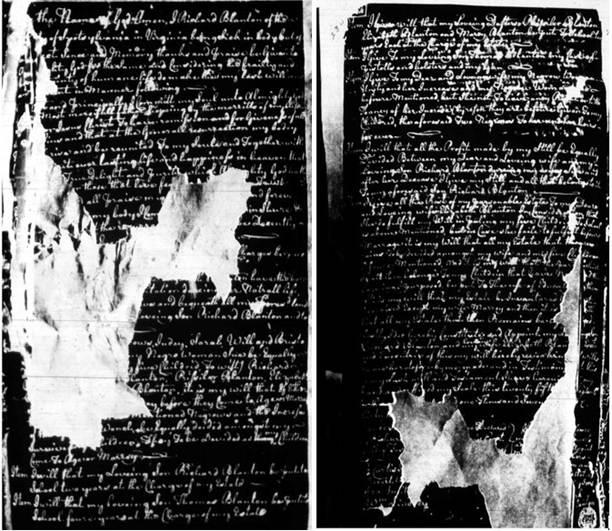

While damaged, Richard Blanton’s still provide much important information, not the least of which are the names of his wife Elizabeth and their five children, including sons Richard and Thomas and daughters Priscilla, Elizabeth and Mary. Unlike his father, Richard Blanton did not divide his land between all of his sons. Instead, Richard Blanton I’s appears to have “lent” his land to his wife for her “natural life” and then it was to go to his son Richard Blanton II, but this portion is particularly damaged. I found no deed for Richard Blanton I having bought any land. It is possible he held a long-term lease for land that could be passed to heirs. With respect to his still operation, Richard I directed that “all the profit made by my still be equally divided between my dear and loving wife and loving son Richard Blanton during my wife’s life and after her decrease I give my still and all that belongs to it to my aforesaid son Richard Blanton.” Lastly, Richard Blanton I named his son Richard Blanton II and his wife Elizabeth Blanton co-executors.

To his other son Thomas Blanton, Richard I left him “my case of pistols and holsters and my gun.” All five Blanton children were to share in the personal estate of their father, which consisted principally of enslaved people. While Thomas Blanton I utilized fixed term indentured servants during the later 1600s, by the 1730s Richard Blanton and most other Virginia planters had shifted to enslaved African laborers who were enslaved for their lifetimes as were their descendants. At the time of his death about 1734, Richard Blanton I held seven enslaved people including three adult women named Unity, Sue and Venus and four children named Judey, Sarah, Will and Bristo.

Richard Blanton I and his wife Elizabeth were both illiterate, each making their marks rather than signing documents. None of Richard’s brothers were literate either. Evidently appreciating the value of an education, Richard I directed that all of his children – both sons and daughters – were to have “schooling” paid for by his estate. Eldest son Richard II was to receive two years of schooling suggesting he had already begun his education. Son Thomas and daughters Priscilla, Elizabeth and Mary were each to receive four years of education paid out of the estate. This suggests the Blanton children were quite young as children usually began their “schooling” around age 6-8.

Without public schools in Virginia, how children were educated depended on economic and social class. educating children was accomplished. The wealthiest planters might have sent their sons, in particular, to England to receive their education. Perhaps they attended one of the few colleges in the American British colonies such as William & Mary in Williamsburg founded in 1693. Private tutors were also utilized. Poor and orphaned children whose fathers had or left no meaningful estates were “bound out” as apprentices to learn a trade serving until they were of age. In addition to teaching the apprentice the necessary trade skills, masters were required to teach their apprentices to read and write, to manage calculations, and the rudiments of the Christian religion. One can imagine how varied inputs and outcomes would have been, but the goal was to ensure people could make a living and function in society and not become a public charge. Children like the Blantons may have attended a so-called “free” school. These were typically small one-room buildings built by one or more planters for their own children. They invited neighbor children to attend by paying a tuition as a way to defray expenses.

To ensure that his wishes were carried out he gave “all the rest of my perishable estate to my dear and loving wife Elizabeth Blanton in consideration she do fulfill my will in putting my five children to school as above mentioned, but in case she fails to fulfill before marriage, it is my will that all of my estate that then exists be divided among my wife and five children aforementioned.” Richard Blanton was providing for his widow in the event she did not remarry and protecting his children’s inheritance if she did so.

An Executrix Duties and a New Executor

On 5 August 1735 Elizabeth Blanton, acting Executrix of Richard Blanton, was being sued by James Sleet for a debt and Elziabeth moved a special imparlance [e.g., more time to answer the plaintiff’s pleading] which was granted by the court.[39] On 2 September 1735, Sleet admitted that the £5.7 debt alleged was less than £5 and nonsuited. He was ordered to pay Elizabeth Blanton’s costs.[40]

On 7 March 1737/8, Benjamin Martin’s petition the court to “have the Estate of Richard Blanton, decd,” which was granted. Anthony Foster, William Barlett, John Parrish and Francis Smith, or any three of them, were ordered to appraise the estate and return to the next court.[41] Martin returned to court on 4 April 1738 with the completed inventory and appraisal which was ordered recorded.[42]

Why does Benjamin Martin get Richard Blanton’s estate? Either he married Richard’s widow or the widow died and he was appointed because the eldest son Richard II was still a minor. As noted earlier, given the provisions of his father’s will related to education, eldest son Richard Blanton had probably already begun whatever education was available to him while the other younger children had not. Richard was probably between 6-8 years old when beginning his studies suggesting he was about 8-10 years old when his father died [b.c. 1725]. The other younger children’s estimated birth years were between 1725-1733.[43]

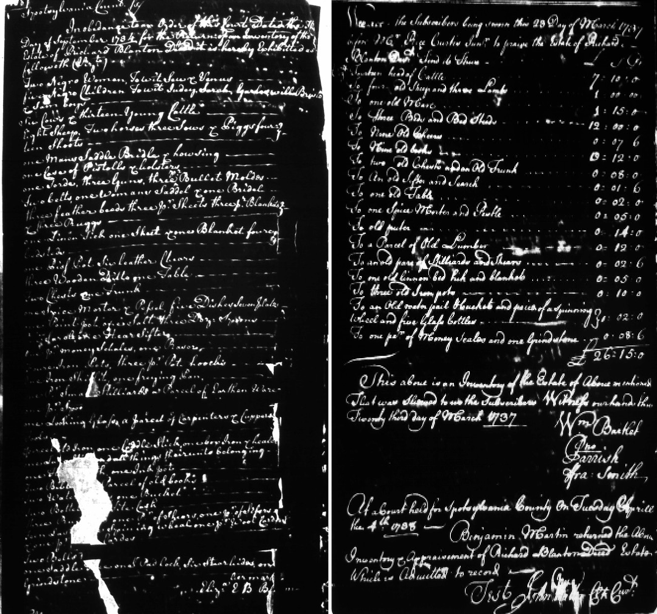

Richard Blanton I’s Estate Inventories & Appraisal

Elizabeth Blanton presented an inventory of Richard Blanton’s estate on 1 October 1734 which was ordered to be recorded.[44] Elizabeth Blanton has to pay Bird Booker for one day’s attendance and 75 miles[45] “coming and going” and William Bartlett for one day’s attendance as witnesses.[46] The second inventory, which includes a £26.15 appraised value, was conducted by William Bartlett, Thomas Parrish and Francis Smith dated 3 March 1737/8, was returned to the court by Benjamin Martin and recorded on 4 April 1738.

The following transcription is of the 1734 inventory presented by Elizabeth Blanton. The items in bold are those NOT included in the subsequent 1738 inventory and appraisal. The omissions represent specific legacies bequeathed by Richard Blanton in his will.

In obedience to an order of this court dated the — day of September 1734 for the return of an inventory of the Estate of Richard Blanton, deced, it is hereby Exhibited as followeth (Vizt)

Two Negro women, To wit Sew & Venus

Five negro children to wit Judey, Sarah, girls, Will, Bristow & Sam, boys

Six cows & thirteen young Cattle

Eight Sheep, Two horses, three sows & piggs, fourteen shoats [young pigs]

One man’s saddle, bridle & housing [decorated covering for a horse[47]]

One case of pistols & holsters

One sword, three guns, three doz bullet molds

Two belts, one woman’s saddle, & one bridle

Three feather beds, three pr sheets, three pr blankets & three rugs

One linen tick, one sheet & one blanket, four bedsteads

One —- pot, six leather chairs

Three wooden ditto [chairs], one table

Two chests, one trunk

One spice mortar & pestle, five dishes, seven plate

One [Point?] pot of — Salt, & three dozen spoons

—— & one ——- sifter

One pr of money scales, one razor

Three iron pots, three pr pot hooks

One iron skillet, one frying pan

One pr small stillards & a parcel of earthenware

One pr Irons[?]

One looking glass & a parcel of carpenter’s & cooper’s tools

Parcel of old iron, one candlestick, one box Iron & heater

One [page torn] & all things thereunto belonging

One ]page torn] one iron pot

Two Bible [torn] parcel of old books

Two water [torn] & one bucket

Two bottles [torn] tight cask

Three Bus [torn] one pr of shears, one pr scissors

One [torn] spinning wheel, one pr [illeg] cards

One [illeg – torn] cards

Two Bottles

One saddle, [torn] and padlock, six steer hides, one grindstone

Richard2 Blanton I, b.c. 1688, (Old) Rappahannock County, Virginia, d.c. 1734, Spotsylvania County, Virginia, m. Elizabeth ———-, issue:

Richard3 Blanton II, b.c. 1725

Thomas3 Blanton

Priscilla3 Blanton

Elizabeth3 Blanton

Mary3 Blanton

[1] Essex County Virginia Deeds and Wills 1695-1699, p. 165; “Essex, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99PC-3SFT?view=fullText : Apr 1, 2025), image 74 of 147 .

[2] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book No. 16 1718-1721, p. 42; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89P6-KQ28?i=32&cat=413447

[3] Essex County Virginia Order Book 5, 1716-1723, p. 422; “Essex, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-2Q1Z-R?view=fullText : Mar 30, 2025), image 260 of 439.

[4] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book 17 (1721-1724), p. 310-312; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89P6-K0XY?i=363&cat=413447

[5] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book No. 9 1695-1699, p. 16; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9P6-3WYH?i=200&cat=413447

[6] Spotsylvania County Virginia Deed Book A 1722-1729, p. 47; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9GF-5CT7?view=fullText : Apr 27, 2025), image 32 of 233; Image Group Number: 004145194

[7] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 54; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFR-1?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 43 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[8] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 146; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HF7-P?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 90 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[9] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 216; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXG-N?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 125 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[10] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 266; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXN-7?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 150 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[11] Valerie M. Fogleman. (1989). American Attitudes Towards Wolves: A History of Misperception. Environmental Review: ER, 13(1), 63–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/3984536

[12] “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXQ-Q?view=fullText : Apr 27, 2025), image 224 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[13] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p.2;

[14] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 200; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HNN-R?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 118 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[15] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 102; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFD-B?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 68 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[16] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 113; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFF-X?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 73 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[17] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 294; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXC-2?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 164 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[18] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 381; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXQ-6?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 207 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[19] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 316; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXC-H?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 175 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[20] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 326; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX6-W?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 180 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[21] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 292; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX6-F?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 163 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[22] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 385; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX9-T?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 209 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[23] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 388; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXW-W?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 211 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[24] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 253; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX8-5?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 143 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[25] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 258; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXV-K?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 146 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[26] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 402; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX3-T?view=fullText : Apr 1, 2025), image 218 of 236.

[27] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 25; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HJM-Q?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 30 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[28] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 39; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HJ3-Z?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 37 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[29] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 90; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HJ9-F?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 63 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[30] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 102; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFD-B?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 68 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[31] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 113; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFF-X?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 73 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[32] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 294; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXC-2?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 164 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[33] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 381; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXQ-6?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 207 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[34] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 316; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HXC-H?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 175 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[35] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1724-1730, p. 326; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX6-W?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 180 of 236; Image Group Number: 007895967

[36] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 238; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HN6-6?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 136 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[37] Spotsylvania County Virginis Order Book 1730-1738, p. 336; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFT-7?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 186 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[38] Spotsylvania County Virginia Will Book A, 1722-1749, p. 240; Reel 26, Library of Virginia; Richmond, Virginia

[39] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 403; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HF8-F?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 222 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[40] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 413; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFZ-P?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 227 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[41] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 535; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HX2-Z?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 287 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[42] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1738-1749, p. 1; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKV-T9VH-4?view=fullText : Apr 27, 2025), image 19 of 303; Image Group Number: 008153251

[43] Education in Colonial Virginia: Part III: Free Schools. (1897). The William and Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine, 6(2), 71–85. https://doi.org/10.2307/1915359

[44] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 348; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HF5-P?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 192 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

[45] This means that Booker traveled 37 ½ miles one way.

[46] Spotsylvania County Virginia Order Book 1730-1738, p. 414; “Spotsylvania, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS46-1HFZ-P?view=fullText : Apr 26, 2025), image 227 of 291; Image Group Number: 007895967

Looking forward to the work on William Blanton. Guessing he was a son of Richard I? My ancestor William Daniel 1680-1765 was also a carpenter who associated with other carpenters. I know William Blanton was alive in 1745 when he witnessed the will of William Daniel’s son’ Moses. i don’t have easy access to Dorman’s transcripts of Caroline Court Order books but plan to visit the genealogy library about two hours from here to look at them eventually.

Kevin Daniel

LikeLike

William was a son of Thomas I. This William also had a son named William. The Caroline County Order Books are online through FamilySearch. Have you tried their new full text search tool? It’s incredible – and free.

LikeLike