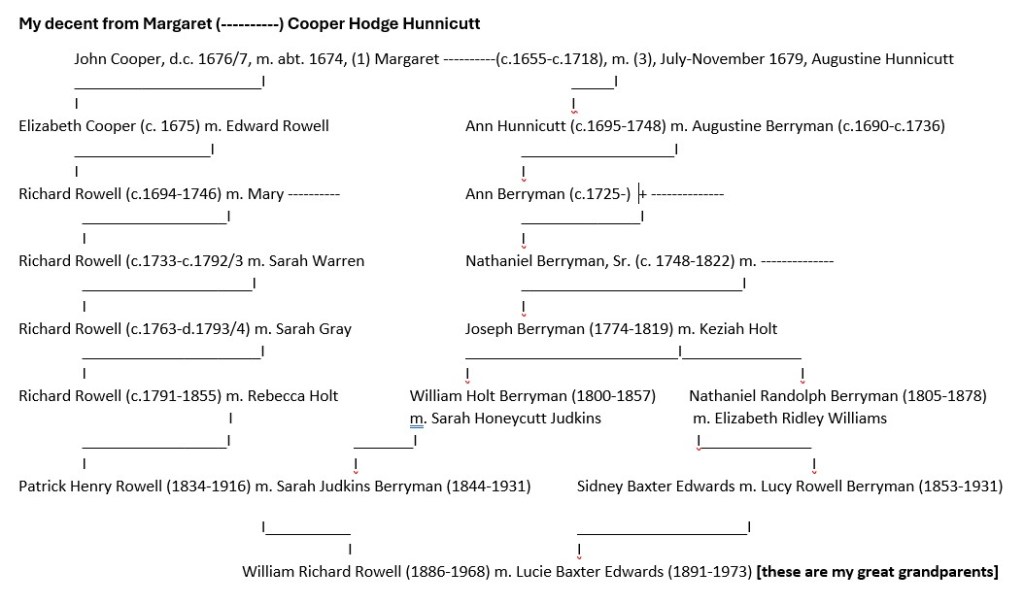

Researching one’s early Colonial Virginia ancestors tends to focus on the men who dominate the records kept not for us researchers, but for them to conduct the business of the day. Sometimes we get lucky and learn more about a female ancestor. Such is the case with my 8x great grandmother Margaret (————) Cooper Hodge Hunnicutt (c.1665-c.1718) of Surry County, Virginia. Margaret was married three times and is an ancestor of numerous old Surry County families. She is often styled as Margaret Phillips and we will get to that, but first here is Margaret’s story.

Margaret (———-) Cooper Hodge Hunnicutt was born about 1655 according to a deposition she gave on 16 July 1677 in the aftermath of Bacon’s Rebellion. Whether she was born in Virginia is not known, but at that time Virginia’s English and African population was about 20,000.[1] As the map below indicates, nearly all were east of Virginia’s Fall Line.[2] By the time she gave her deposition in 1677, Virginia’s population had more than doubled to about 44,000.[3] Not only did Margaret live during a time when Virginia’s English and African population was increasing rapidly, Margaret was an eyewitness to a period of major social upheaval.

Margaret’s Deposition

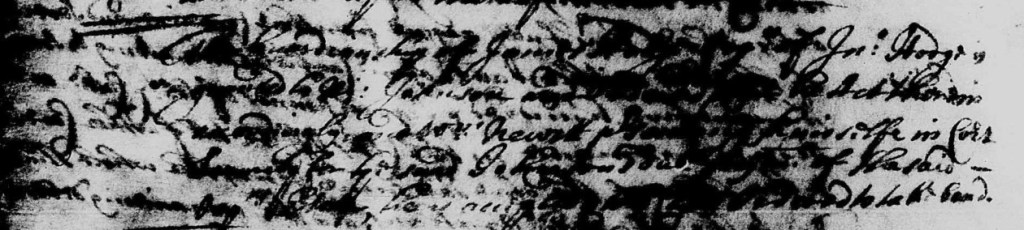

Many depositions were taken after the Governor’s forces defeated the Baconian Rebels – part of the process of meting out of “justice.” At the time of her testimony, Margaret, “aged about 22 years,” was married to her second husband John Hodge, but she was testifying about her late husband John Cooper. On 3 July 1677, Margaret told the court:

“That very shortly after Mr Arthur Allen[6] was (by ye late wicked Rebells forced from his house, my deced Husband Jno Cooper, found a Sadle w:h houlsters, brest plate, crupper[7] & new half cheek’d bridle of ye sd Mr Allen’s as alsoe some other Sadles, but out of a p’ticular respect [for] Mr Allen to ye goodness of his sd Sadle & other furniture to secure the same it was put up into a Chest, but some short time after, Joseph Rogers[8] came to this deponts [deponent’s] house & demanded three Sadles[9] of her, to which ye depont riplyed yt he should have none there for there was none, but ye sd Rogers swearing to ye depont yt shee lyed tould he yt sd Allens Sadle was in her chest & he would have that, & there upon ye depont step’d toward ye chest where ye Sadle was to lock it, but the sd Rogers pushed her away & forceably tooke & carried away the sd Allens Sadle houlsters brass plate crupper, & half cheek’d bridle, And further saith not.”[10]

Note: “ye” and “yt” were abbreviations for the words “the” and “that” respectively. Colonial handwriting, especially from the 1600s can be difficult to read. Go ahead and give Margaret’s deposition a try.

While Margaret’s deposition is interesting in and of itself, what is important for me is the genealogical information. Specifically, her first husband John Cooper was alive “shortly after Mr. Arthur Allen was forced from his house.” Surry Rebels, including the aforementioned Joseph Rogers who “pushed away” Margaret in pursuit of Arthur Allen’s property, held Allen’s house from 18 September until 27 December 1676.[11] Arthur Allen’s Brick House, known as Bacon’s Castle, was built in 1665 and is the oldest brick dwelling in North America. It is now owned and maintained by Preservation Virginia and is open for tours and a variety of special events.[12]

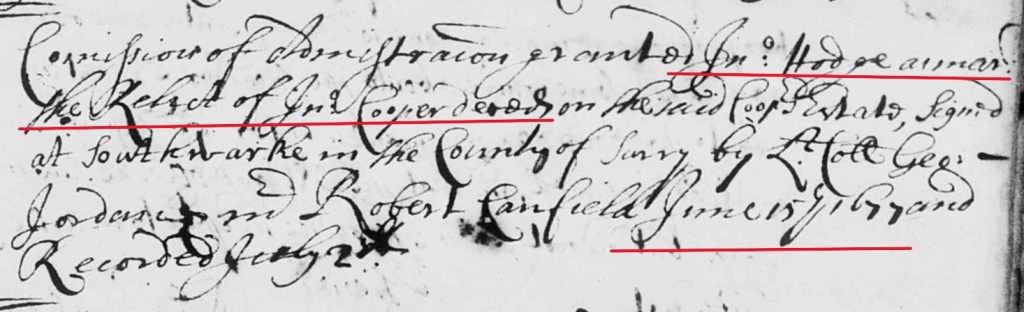

By 5 May 1677, when Cooper’s estate inventory was taken, Margaret was already married to John Hodge “who married the relict of John Cooper” and was granted administration of Cooper’s estate.[13]

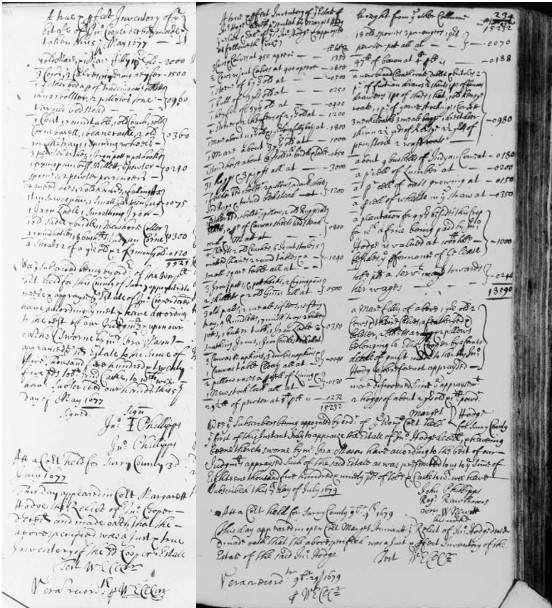

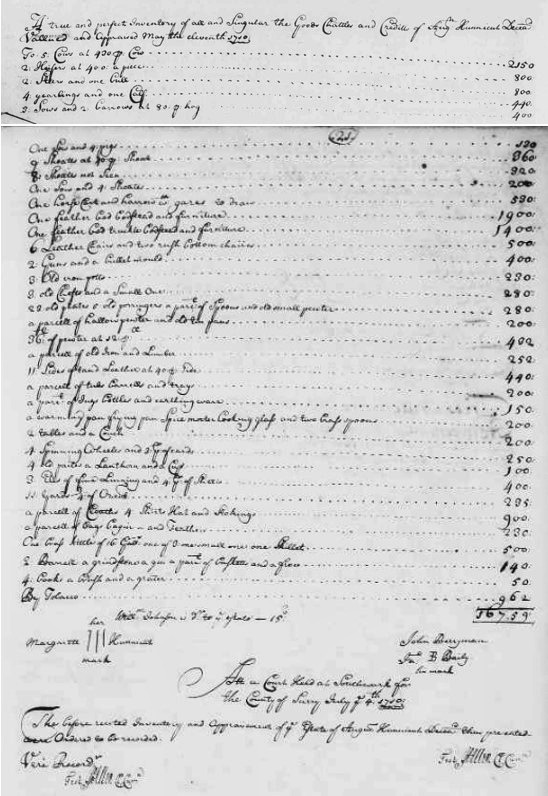

John Cooper owned no land and his estate principally consisted of livestock, household furniture and kitchen tools valued at 5,525 pounds of tobacco.[14] On 1 January 1677/8, John Hodge calculated the debts owned by Cooper’s estate, which totaled 2,801 lbs of tobacco leaving an estate value of 2,724 lbs of tobacco. He claimed one-third of that amount in right of his wife with the other two-thirds going to her only child Elizabeth Cooper.[15]

Margaret’s second marriage proved to be short lived as John Hodge made his will on 17 May 1679 and a twice widowed Margaret (———-) Cooper Hodge presented his will at court on 1 July 1679. Hodge’s will directed that his debts be paid and bequeathed the remaining part of is estate to his “loving wife Margett & and my two children James and Mary Hodge to be justly and equally divided.”He also gave one heifer yearling to his “wife’s daughter Eliz: Cooper.”

With respect to his young children, Hodge directed that his son James Hodge was to have his estate at the age of 18 and daughter Mary at age 15 and that if either child died the other would inherit the estate. Lastly he named his wife Margaret executrix and friends Robert Ruffin and William Newsum overseers of the will.[16] By the time Hodge’s estate inventory and appraisal was presented at court on 29 November 1679 – less than four months after John Hodge’s death – Margaret had married for the third and final time to Augustine Hunnicutt, Jr. (c.1662-c.1710).[17]

Compared to John Cooper, John Hodge left a sizeable estate although he owned no land. Hodge’s inventory was valued at more than 18,000 pounds of tobacco. After an accounting for debts owed to and from the estate, John Hodge’s widow Margaret and his children James Hodge and Mary Hodge each inherited one third of an estate valued at 13,400 lbs tobacco.[18]

On 24 April 1680, Margaret’s third husband Augustine Hunnicutt, Jr. obligated himself to the Surry Court for 40,000 lbs of tobacco with Roger Rawlings and John Prince as his securities. Hunnicutt’s obligation was to ensure that he paid Elizabeth Cooper, orphan of John Cooper, her portion of her father’s estate when she reached “lawful age.” Hunnicutt also promised to teach Elizabeth Cooper the “rudiments of the Christian religion” and to provide her with lodging, food and clothing.[19]

Hunnicutt did the same on 2 November 1680, this time with William Seward and William Foreman as his securities, for the purpose of paying the orphans [unnamed] of John Hodge “a child’s part of the goods and chattles of their late father when they shall come of lawful age.”[20] Augustine Hunnicutt was now head of a household that included he and Margaret and three children all under the age of five. Then something terrible happened.

Surry Court finds that Margaret shamefully abused the orphans of John Hodge

On 1 March 1680/1, Margaret found herself the subject of a Surry County Court order. The Surry Court “having this day rec’d credible information that Margaret the wife of Augustine Hunnicutt Junr doth shamefully abuse the orphans of Jno. Hodge decd.” The abuse was apparently so bad that Robert Ruffin, one of the overseers of John Hodge’s will, was ordered by the court to “place the said orphans with such persons to him shall be thought meete [&c]”[21]meaning removal from her custody.

While I found no record of Mary Hodge being placed with another family, six months after the abuse allegation James Hodge’s guardianship was granted to Nicholas Johnson on 6 September 1681.[22]

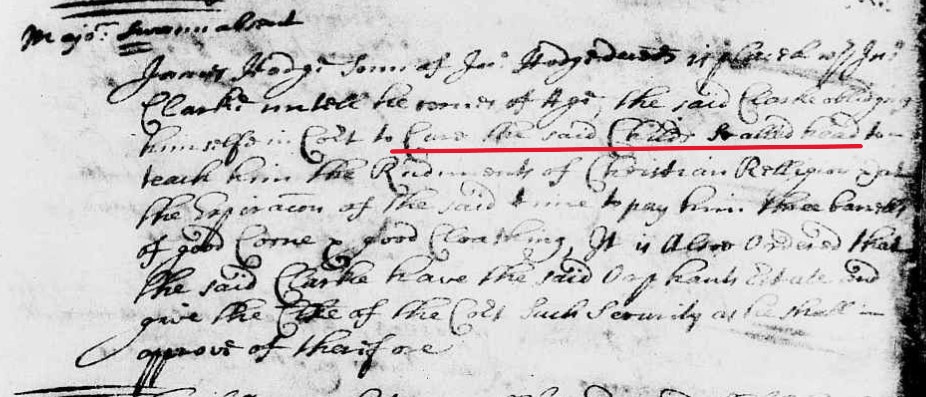

That situation proved temporary as four months later on 11 January 1681/2, James Hodge was bound to John Clarke, his father’s friend and will overseer, until he “comes of age.” Clarke agreed to “cure the said child’s scalded head” and to teach him the rudiments of the Christian religion. Clarke also agreed that at the expiration of the said time to pay him three barrels of good corn & good clothing. The court also ordered Clarke to “have the said orphan’s estate” and give security.”[23]

What Happened Here?

The scant evidence suggests that Margaret was responsible for very seriously scalding a five-year-old child. The court found it so serious that they ordered James Hodge’s removal from the custody of Augustine and Margaret’s home and bound him to John Clarke who was also now in charge of James Hodge’s estate. The injury must have been significant as 10 months after it was sustained, the Surry Court mentioned “curing” it in their order to his new guardian John Clarke. I’ve studied a lot of colonial Virginia records and I have read suits brought by young, indentured servants alleging cruelty by their master and vestries stepping in on behalf of a starving children in a poor families. This is the first time I have found a case where a child was removed from a family home due to abuse.

Perhaps it was because James Hodge was not Margaret’s son. James Hodge’s first appearance on Surry County tithe lists is on 8 June 1692 as a tithable of John Clarke[24] and on 15 September 1696, James Hodge, son of John Hodge deceased, appeared at court and acknowledged having received from John Clarke the “full of my decd fathers estate” and then discharged Clarke from his responsibility as guardian.[25] White males became tithable in the year they were 16 years old on 10 June. James Hodge turned 16 between 11 June 1691 and 10 June 1692. Having reached 21 by 15 September 1696, these two records establish that James Hodge was born between 11 June 1675 and 15 September 1675.

Remember Margaret’s 1677 deposition about her husband John Cooper? He was still alive in September 1676 so Margaret cannot be his mother. Given Mary Hodge, absent in the record until Margaret made her will calling her “my daughter,” was not moved from the Hunnicutt home we conclude she was, in fact, Margaret’s daughter.

Was Margaret’s scalding of James Hodge an accident? The Surry Court certainly did not think so. Was it ongoing abuse (no laws protecting children back then) or was it something more sinister?

When John Hodge made his will in 1679, he divided his 13,400 lbs of tobacco estate “justly and equally” between wife Margaret and children James and Mary. That amounted to about 4,466 lbs each. Compare that to John Cooper’s 1677 estate value of 2,724 lbs of tobacco, of which Margaret received one-third (908 lbs) and Elizabeth Cooper got two thirds (1816 lbs). Notably John Hodge’s will contained a directive that if either of his children should die, the other was to receive their portion. One cannot help but wonder if this provided Margaret with a motive for murder. Were her stepson to die, her daughter Mary Hodge would have stood to gain a much larger estate. However, as the record is devoid of anything further on the whole affair, we are left to wonder.

Margaret Hunnicutt

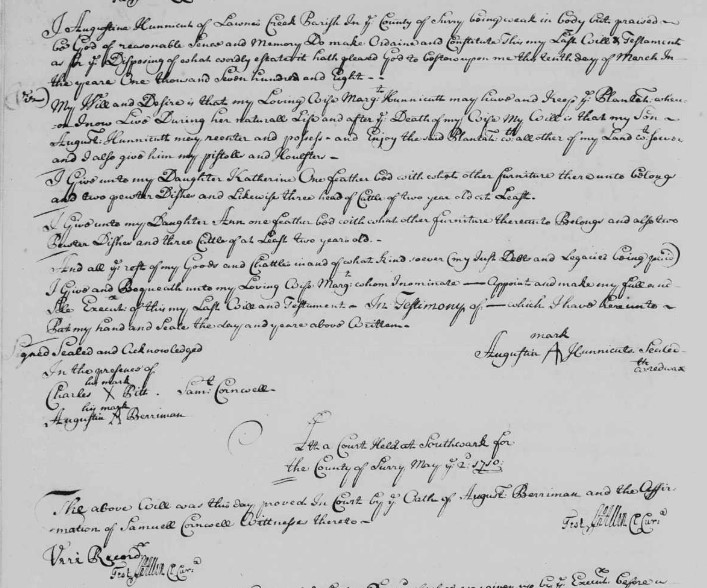

There is little else in the record about Margaret. While her first two marriages were short lived, her third marriage to Augustine Hunnicutt II lasted more than 30 years and produced three more children. Augustine Hunnicutt II made his will on 10 March 1708 and was dead by 2 May 1710 when his will as recorded. He gave Margaret, now about 55 years old, use of his plantation for life. After her death, it was to go to their son Augustine Hunnicutt III who was also given his father’s pistols and holsters. Daughters Katherine and Ann each received a feather bed, pewter dishes and three head of cattle. Margaret was named as executor.[26]

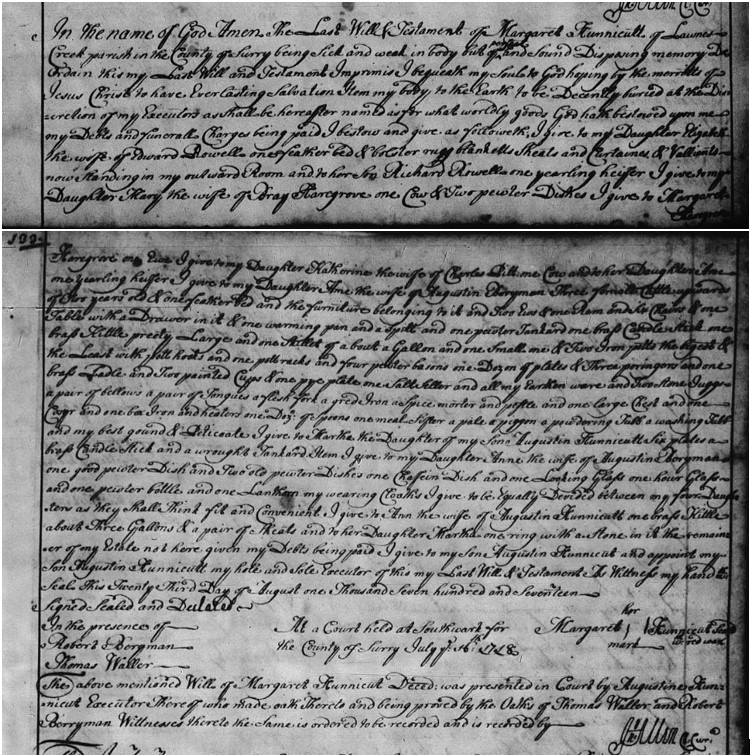

Margaret (———-) Cooper Hodge Hunnicutt survived her husband by about eight years making her own will on 23 August 1717. She died before it was on 16 July 1718 at about 62 years old. Margaret’s will named her daughter Elizabeth, wife of Edward Rowell and her son Richard Rowell. This is Elizabeth (Cooper) Rowell. She and Edward Rowell were married by 2 January 1693/4 when he appeared at court to acknowledge having received Elizabeth’s inheritance from Augustine Hunnicutt.[28] She named daughter Mary, the wife of Bray Hargrave and her daughter Margaret Hargrave. This is Mary (Hodge) Hargrave. Then she named her three Hunnicutt children including daughter Katherine, wife of Charles Pitt and their daughter Ann Pitt, daughter Ann, wife of Augustine Berryman and their daughter Martha Berryman. Finally, she named her son Augustine Hunnicutt III as her executor.[29]

Was she Margaret Phillips?

Margaret (———-) has been identified as Margaret Phillips for many, many years. There certainly are records pertaining to Margaret (———–) Cooper Hodge Hunnicutt that involve people named Phillips. In particular, the 5 May 1677 estate inventory and appraisal for Margaret’s first husband John Cooper conducted by father and son John (X) Phillips and John Phillips Jr.[30] On 17 May 1679, William Newitt, John Phillips and William Liles witnessed the will of Margaret’s second husband John Hodge.[31] When Margaret was granted probate on 1 July 1679, William Newitt and John Phillips, Jr. were her securities.[32] Finally, on 7 July 1679, John Phillips, Roger Rawlins and William Newitt presented the estate inventory and appraisal of John Hodge.[33] Note that both Phillips and Newitt appear multiple times.

During this same time period we find other records involving Phillips and/or Newitt that have nothing to do with Margaret. On 4 May 1679, William Blunt, John (X) Phillips and Alice Phillips witnessed the wil of Edward Davids.[34] On 28 June 1679, William Newsum, William Newitt and John Phillips (Jr) conducted the estate inventory and appraisal of Lewis Williams.[35] On 19 July 1679, Joseph Rogers and John (X) Phillips were securities for Sion Hill for his being the administrator of the estate of John Spiltimber.[36] Finally, on 15 September 1680, the will of Walter Tayler was witnessed by Stephen Allen, Thomas Drew, Joseph (X) Rogers and John Phillips.[37]

John Phillips, Sr. made his will on 25 July 1689 and was recorded on 3 March 1690 in Surry County in which he names his wife Alice, son John, and daughters Jane and Alice Phillips.[38] There is no mention of Margaret.

In 1677 there were 103 households in with 213 tithables consisting of white men 16+and male and female servants/slaves 16+ in Lawnes Creek Parish. The households were spread out on small owned or rented farms to large plantations. They counted on their neighbors to be witnesses to deeds and wills. The court routinely appointed close by neighbors to conduct inventories and appraisals. People naturally counted on family and close friends to serve as security for legal and financial obligations. While it is certainly possible Margaret was a Phillips, on balance the evidence seems weak to make that claim. Nonetheless, Margaret (———-) Cooper Hodge Hunnicutt is an ancestor of many old Surry families and below is how Margaret is related to me.

[1] Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, US Census Bureau; https://archive.org/details/HistoricalStatisticsOfTheUnitedStatesColonialTimesTo1970/page/n1231/mode/2up

[2] The Fall Line separates the Tidewater and Piedmont regions of Virginia and is where navigable waters ended on Virginia’s principle settled river banks – the Potomac, Rappahannock, York and James. Coastal Plain Physiography, Radford University; https://sites.radford.edu/~jtso/GeologyofVirginia/CoastalPlain/CPPhysio-15.html

[3] Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, US Census Bureau; https://archive.org/details/HistoricalStatisticsOfTheUnitedStatesColonialTimesTo1970/page/n1231/mode/2up

[4] Doran, Michael F. Atlas of Boundary Changes in Virginia 1634-1895 (Athens, GA, Iberian Publishing Company, 1987), p. 11.

[5] Coastal Plain Physiography, Radford University; https://sites.radford.edu/~jtso/GeologyofVirginia/CoastalPlain/CPPhysio-15.html

[6] Arthur Allen (c.1652-1710) was a planter, merchant and Surry County Justice. He inherited from his father of the same name, a large brick house occupied by the Surry Rebels, which became known as Bacon’s Castle.

[7] A crupper was a type of body armor covered in leather to protect the chest. Crupper Plate, The Metropolitan Museum, Arms and Armor; https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/27202

[8] Joseph Rogers was one of the Surry Rebel leaders.

[9] Interestingly, Allen reported three saddles among the numerous items taken from his house by the rebels.

[10] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. Book 2 1671-1682, p. 134; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZSP?view=fullText : Feb 8, 2025), image 150 of 383.

[11] A Brief History of Bacon’s Castle, U.S. National Park Service; https://www.nps.gov/jame/learn/historyculture/a-brief-history-of-bacons-castle.htm

[12] Bacon’s Castle, Preservation Virginia; https://preservationvirginia.org/historic-sites/bacons-castle/

[13] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 129; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZQM?cat=366316&i=400&lang=en

[14] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 132; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZSS?cat=366316&i=403&lang=en

[15] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 161; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZS4?cat=366316&i=432&lang=en

[16] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 212; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCB9?cat=366316&i=483&lang=en

[17] On 7 July as Margaret Hodge, John Hodge’s I&A was completed and on 4 November 1679 as Margaret Hunnicutt, she came to court to record Hodge’s I&A. Surry County Virginia Wills, Etc. Book 2 1671-1682, p. 234; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCTF?view=fullText : Feb 3, 2025), image 250 of 383.

[18] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 263; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCPK?cat=366316&i=534&lang=en

[19] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, Image 639 of 746 [this is one of several upside down unnumbered pages at the back of Book 2]; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCC1?cat=366316&i=638&lang=en

[20] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, Upside down pages back of Book 2, Image 673 of 746; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCZ2?cat=366316&i=636&lang=en

[21] Surry County Virginia Court Orders, Part 1, 1671-1691, p. 335; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-X9BL-Q?cat=374004&i=270&lang=en

[22] Surry County Virginia Court Orders, Part 1, 1671-1691, p. 350; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-X9BJ-V?cat=374004&i=278&lang=en

[23] Surry County Virginia Court Orders, Part 1, 1671-1691, p. 361; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-X9BL-V?cat=374004&i=283&lang=en

[24] 1692 Tithe List for Lawnes Creek Parish. Surry County Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 4 1687-1694, p. 280; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-VSR5-Y?cat=366316&i=316&lang=en

[25] Surry County Virginia Deeds and Wills, Etc. 5, part 1, 1694-1709, p. 113; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-V397-Z?view=fullText : Feb 3, 2025), image 129 of 243.

[26] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills Etc. No. 6 1709-1715, p. 6 ; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-V39X-X?cat=366316&i=486&lang=en

[27] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, etc. No. 6 1709-1715, p. 20; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-V39D-G?cat=366316&i=493&lang=en

[28] Surry County Virginia Court Orders 1691-1713, p. 99; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-JQ8N-Z?view=fullText&keywords=Rowell%2CCooper&lang=en&groupId=M9JB-DZ9

[29] Surry County Virginia Will Book 7 1715-1730, p. 132; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-29XQ-7?cat=366316&i=157&lang=en

[30] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 132; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZSS?cat=366316&i=403&lang=en

[31] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc. No. 2 1671-1684, p. 212; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCB9?cat=366316&i=483&lang=en

[32] Surry County Virginia Court Orders part 1 1671-1691, p. 255; “Surry, Virginia, United States records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-X9BQ-B?view=fullText : Feb 3, 2025), image 230 of 304.

[33] Surry County Virginia Wills, Etc. Book 2 1671-1682, p. 234; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCTF?view=fullText : Feb 3, 2025), image 250 of 383.

[34] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc., Book 2 1671-1682, p.212; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCB9?view=fullText : Feb 8, 2025), image 228 of 383.

[35] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, etc., Book 2 1671-1682, p. 238; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KCR4?view=fullText : Feb 8, 2025), image 254 of 383.

[36] Surry County Virginia Deeds, Wills, Etc., Book 2 1671-1682, p. 19; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-KZ8R?view=fullText : Feb 8, 2025), image 29 of 383; .

[37] Surry County Virginia Deeds and Wills Book 4 1687-1694, p. 105; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-VSTW-8?view=fullText : Feb 8, 2025), image 138 of 397.

[38] Surry County Virginia Deeds and Wills Book 4 1687-1694, p. 185; “Surry, Virginia, British Colonial America records,” images, FamilySearch (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-VST8-3?view=fullText : Feb 3, 2025), image 219 of 397.

Great and thorough study! Reading it was interesting and educational. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Connie! So nice of you to write. Steve

LikeLike