Among the witnesses was Judith Webster who testified that the now deceased Thomas Webster II told her that he was not giving any land to his son-in-law John Gibbs due to his “villainy in debauching a sister of his said wife Mary after their intermarriage.”

Thomas Dyer testified that Thomas Webster II did not give Gibbs the land because of Gibbs “affronting him greatly in cohabitating with his, the said Gibbs wife’s sister after intermarriage.”

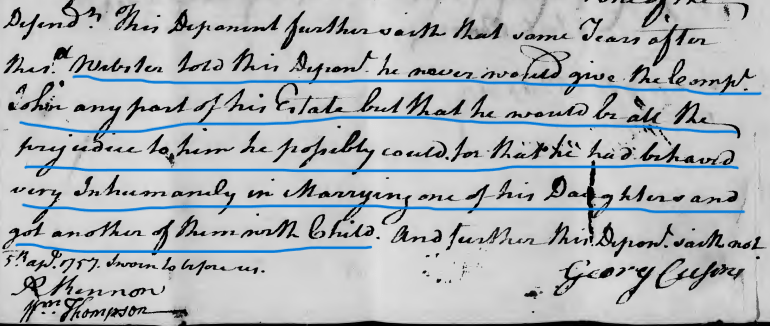

George Cousins testified that Thomas Webster II told him that he “would never give Gibbs any part of his estate as he had behaved very inhumanely in marrying one of his daughters and got another of them with Child.”

These were among the statements made in depositions underway in the Amelia County Chancery Court suit brought in March 1755 by John and Mary (Webster) Gibbs against Peter Webster & Thomas Webster III, executors of Thomas Webster II and Charles Cousins.[1] At issue was a 150 acre tract of land in Amelia County that Gibbs asserted Thomas Webster II had promised him as his daughter Mary’s dowry, but when Webster died in 1748, left it to another daughter Rosamond and her husband Charles Cousins.

Well, well, well. Sounds like a complicated situation. Family gatherings must have been a barrel of laughs.

Thomas Webster II

Our story begins many years earlier with my 7x great-grandfather Thomas Webster II, the son of Thomas and Rosamond (———-) Webster. He was born about 1690 in Henrico County, Virginia. His father died when he was just a year old leaving his mother with five children between the ages of five and one. While his father did not leave a will, Thomas II as his father’s heir-at-law, inherited 900 acres of land on the north side of the Appomattox River on Old Town Creek in then Henrico County (became Chesterfield County in 1749) acquired by five grants issued between 1665 and 1692.

In 1694, his mother Rosamond (———-) Webster, decided to remarry. Henry Hill, who was a neighbor of the widow Webster, filed an unusual and interesting premarital deed in which he gave her children 450 acres of his 733 acre tract and later gave Rosamond and her heirs the remaining 283 acres. Hill also gave them livestock and 10,000 pound of tobacco. Hill’s land was adjacent or nearly so to her son Thomas Webster’s 900 acres – who was only about four years old, effectively giving Rosamond (———-) Cousins Webster Hill control of more than 1600 acres of land. For that story and others visit https://wordpress.com/posts/asonofvirginia.blog.

Thomas Webster II turned 21 in 1711 and appeared at the Henrico County Orphans Court on 20 August to acknowledge that “he had received the estate [inheritance] that was due him” from Charles Cusens [Cousins] (his older half-brother and presumed guardian) and discharged Cousins from his responsibility of managing and protecting the estate.[2]

Thomas Webster II married Mary (———-) about this time and began having the six children they would have by 1720:[3]

Peter Webster, b.c. 1712[4], m. unknown

Rosamond Webster, b.c. 1714, m. 1737, Charles Cousins, Jr. (her half first cousin)

Mary Webster, b.c. 1715, m. 1741, John Gibbs[5]

Elizabeth Webster b.c. 1716, m. after 1747, William Royall

Ann Webster, b.c. 1718

Thomas Webster, b. 1720, d. 1785, Amelia County, Virginia, m. unknown

By 15 April 1732, Thomas Webster II’s wife Mary was dead and he had married Prudence (———-).[6]

Thomas Webster II’s last will and testament

Perhaps Thomas Webster II thought he was settling the matter when he wrote his will on 10 December 1747, which was recorded the “first Monday in April” 1748.[7] After all, he was leaving his wife and children a considerable estate that included 2,100 acres – an inherited 900 acres on both sides of Old Town Creek in Henrico County (became Chesterfield County in 1749) and 1200 acres in Amelia County.

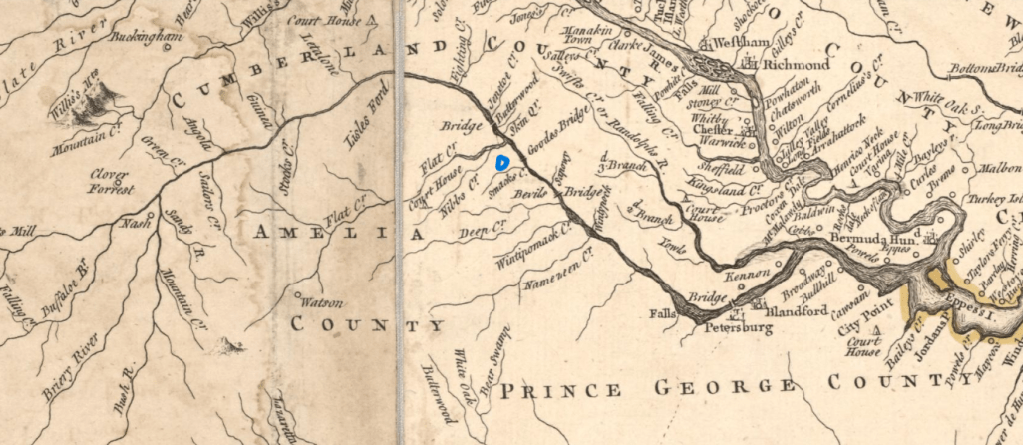

Thomas II acquired the land in Amelia County when it was still in Prince George County in the form of two grants. The first, in 1726, was for 800 acres “in the forke between Smacks Creek and Appomattox River” and the second, in 1734, was for 400 adjacent acres “on the upper side of Smacks Creek on both sides of the Wolfe Branch.” The 1734 grant mentioned adjacent landowners George Wilson, Essex Worsham, John Gibbs (Sr.) and John Garrott [8],[9] These tracts fell into the newly formed Amelia County when it was created in 1734.

When Thomas Webster II wrote his will he divided his estate as follows:

To son Peter Webster – the plantation he lives on in the County of Amelia including 450 acres of land, 100 acres of which is to be taken out my last survey of 400 acres adjoining him. Also, all the stock of cattle, hogs, and all the household goods that are in his possession. Also, half my large brass kettle and one pair of pistols & holsters. Also, half of the land I now live on in the County of Henrico on south side of the Old Town Creek being the lower half of the said land.

To son Thomas Webster – 450 acres in the County of Amelia being the lower part of my survey & where John Blanchet formerly dwelt. Also, all the stock of cattle, hoggs, & one horse & mare and foal now on the plantation, also one oval table, one Carrabine [carabine[11]], one sword, a pair of pistols & cartouche box [ammo box], one large bible, all my carpenters and joyners tools, cooper’s tools & Masonakers [masonry] tools, and half my large brass kettle.[12] Also, my negro man named Jemmy.

To wife Prudence Webster – use and occupation of the upper half or moiety of the land & with the plantation I now live on lying on the southside of Old Town Creek during her natural life and at her death to son Thomas.

To daughter Rosamond Cousins and the heirs of her body lawfully begotten – 150 acres in Amelia County on the south side of Deep Gully being part of a 400 acre tract [100 acres of this tract devised to son Peter]. Also, 150 acres in Amelia on both sides of Wolf Branch being also part of the aforesaid tract of 400 acres.

To daughter Elizabeth Webster and the heirs of her body lawfully begotten – 100 acres in Henrico on north side of Old Town Creek.[13]

To daughter Anne Webster and the heirs of her body lawfully begotten, 100 acres joining above tract.

To son Thomas, rest of my land on north side of Old Town Creek.

To wife, use of negro man named Sezar for her natural life then to grandson John Webster [son of Peter Webster].

To daughter Mary Gibbs, leather trunk that was her mother’s

To wife and daughters Elizabeth, Rosamond and Anne, each ¼ of estate not already divided.

Col. William Kennon to be superadvisor to will and sons Peter and Thomas, Executors.

Wit: Wil. Kennon, William Worsham, James Old

The Gibbs have a story to tell

John and Mary [Webster] Gibbs didn’t receive much of anything – just and old trunk. In fact, she was the only child of Thomas Webster II not to inherit any land. In a further slight, while Thomas Webster’s wife Prudence and his daughters Elizabeth, Rosamond and Ann were to split whatever was left – the “residue” of the estate – daughter Mary was again excluded. The Gibbs were not happy about it – or at least John Gibbs wasn’t.

In March 1755, John and Mary (Webster) Gibbs asked the Amelia Chancery Court to overturn a portion of Thomas Webster II’s will. At issue was the 150 acres of land on Deep Gully willed to daughter Rosamond and her husband Charles Cousins. In their bill of complaint, John and Mary Gibbs accused Cousins and executors Peter and Thomas Webster III of “combining and confederating together to wrong your orator and oratrix.” Gibbs asserted that Thomas Webster II had verbally promised him this particular tract of land if Gibbs married his daughter. Charles and Rosamond (Webster) Cousins sold this tract to her brother Peter Webster on 25 Sep 1754 for £60 pounds, which may have triggered the lawsuit.[14]

Gibbs asserted Thomas Webster II told him when he and Mary Webster were courting that he would give them the 150 acres and “relying on the promise of the said marriage portion made by the said Thomas and not doubting but that the said Thomas would comply therewith did with the consent of the said Thomas intermarry with Mary Webster.” Gibbs further argued that he had approached Thomas Webster “often” about conveying [executing a deed] the land, but that Webster “always by some trifling pretenses delayed” and that “pretending that it would be of great expense and charge” to Gibbs and told him he would leave it to him in his will. Finally, Gibbs argued they “were rendered helpless . . . by the strict rules of the Common Law and can’t compel a performance of said promise & gift aforesaid without the aid and assistance of this worshipful court.”

The Gibbs then provided as evidence an earlier will written by Thomas Webster II dated 27 October 1738. This version differed from the 1747 will in two material respects. First daughter Rosamond was to receive “150 acres in Amelia County being on both sides of a gully commonly called Deep Gully being part of a tract of 400 acres” and daughter Mary was to receive “one moiety or half of my land in the county of Henrico on the north side of Old Town Creek – she to have the upper half.” Secondly, 1/5 of the residue of the estate was left to wife Prudence and his four daughters including daughter Mary.

In their answer to the lawsuit defendants Charles Cousins, Peter Webster and Thomas Webster III simply denied they ever knew or heard of Thomas Webster II promising anything to John Gibbs.

Many witnesses deposed

Depositions were taken during 1756 and early 1757 as part of the suit.

For the plaintiffs:

Thomas Deaton – plaintiff John Gibbs, Jr.’s brother-in-law[15] – said he heard a conversation between Thomas Webster and John Gibbs who, at the time, was courting Webster’s daughter. He testified that Webster told Gibbs he could choose between a tract of land in Amelia County or a tract in Chesterfield County as a “portion for the daughter” who was contracted to marry Gibbs. Deaton offered that “upon reflection” Gibbs chose the tract in Amelia because it was adjacent to a tract he owned. Deaton added that after the celebration of marriage between Gibbs and Mary Webster, Thomas Webster II “again gave Gibbs the choice and he chose the land in Amelia.” Deaton offered that Webster added that he would make a conveyance [deed] at any time to Gibbs. Deaton added that Webster said he once had an intention to give the land to Charles Cousins, but further said that he [Gibbs] should have it as Cousins was a “troublesome man.”

William Purkinson – neighbor of Thomas Webster II[16] – he heard Mr. Webster say he had given his daughter Rosamond Webster and Mary Webster their parts of land – land in Amelia County on the Gully Branch or Wolf Branch on which of these branches he could not remember.

John Gibbs, Sr. – father of the plaintiff[17] – said he was at Webster’s house the morning before they [Gibbs and Mary Webster] were married and that Webster told him he would give his daughter 150 acres of land in Amelia or Chesterfield at Gibbs’ choosing and if in Amelia the land on the Gully Branch.

Elizabeth Deaton – plaintiff John Gibbs, Jr.’s sister-in-law[18] – testified that “some small time after Gibbs married Webster’s daughter” she heard Webster say he had given John Gibbs choice of two tracts containing 150 acres each – one in Chesterfield and one in Amelia. Land in Amelia joined Peter Webster and in Chesterfield joined John Gibbs, Sr. Deaton said that Webster was surprised Gibbs asked for a deed. She added that Webster said he had intended to give the land to Charles Cousins, but never had mentioned it to Cousins and because he was a “troublesome person” he did not want Cousins to live near his children and that he “never should own the land.”

For the defendants:

Thomas Bevil – nephew of Thomas Webster II[19] recalled a conversation with Thomas Webster II in 1740 – to the best of his knowledge – in which Webster said he was going to give the 150 acres in question to Charles and Rosamond (Webster) Cousins. Bevil said he told Webster that it “might be of ill consequence to do so, as in all probability his daughter [Mary] would marry [John Gibbs] & then Peter Webster, one of the defendants, would be obliged to pay dear for the said land at some day or other” – Peter having adjacent land. Bevil went to on to say that Webster – after pausing for some time – said “you are right, but my word is out & she shall have it.”

Bevil added that about 1742 he was at Webster’s house and Webster was out for a walk leaving him to talk to Mrs. Webster who mentioned that she thought a wedding would soon take place between John Gibbs and Mary Webster and she thought “it would be a good way” for her husband to give the aforesaid land to John & Mary as they would likely live there and to “let Rosamond have a piece in Henrico” and that she asked Bevil to mention it to her husband when he returned. Upon his return Webster said that he also believed that Gibbs and his daughter would “make a match of it” and that he had no objection. Bevil then said that he “thought it a very convenient time to ask him what he thought of giving Mary the land he had promised or given to Rosamond.” He said that Webster “looking very sternly” and “seeming to be angry” and said “No, that he never was worse than his word in his life, nor would he be then, for he had given Rosamond the land in Amelia and though it might be more suitable, as matters were, to give it to Mary, yet he never would take it from Rosamond if he could.” Mrs. Webster, who had stepped out, came back in and said, “Thomas Webster I really think it will be the best way to let Mary have that land” to which her husband answered, “Prue, you know very well I have given Charles Cousins and his wife that piece of land already so say no more about it.”

Judith Webster – probably wife of either Peter Webster or Thomas Webster III[20] testified that about the year 1737 she was at Thomas Webster II’s home together with the defendants Charles & Rosamond (Webster) Cousins. She stated that Thomas II took occasion to tell Charles Cousins that he had some time before made his will in devised a piece of land lying upon the gully and Amelia county adjoining Garrett’s [Garrott] line to his daughter Rosamond and since the said Charles had married her it was his and he must pay the quitrents [tax] for it. She indicated that Charles Cousins said he would pay and believed he did so since the tax was not paid afterward by Thomas Webster II.

Judith Webster added that Thomas II told Charles Cousins that if he was afraid to trust his giving him the land by will at his death, he would ride up to Amelia Court at any time and acknowledge the deed to him, provided Cousins would bear the expense of getting one prepared, to which Cousins answered, “you are counted so honest a man that your word is your bond and I’m not the least distrustful of you.” She added that to the best of her remembrance all the family were present and particularly Mary (Webster) Gibbs when Thomas II made his declaration and that the reason he was not giving the land to Gibbs was “owing to his villainy and debauching a sister of his said wife Mary after their intermarriage.”

Isaac Garrott – Amelia County neighbor of Peter Webster and Thomas Webster III[21] testified that about 1745 after Gibbs intermarriage to Mary Webster and before “the affront given by him to the said Thomas Webster, deceased.” that he had approached Thomas Webster to see if he could buy part of the land in dispute, but was told by Webster that he must go to Charles Cousins “for he had given it to him long ago and had no right to sell it.”

Robert Cousins – brother of defendant Charles Cousins, Jr.[22] testified that about four to six years ago [1750-1752] after the death of Thomas Webster II [d. 1748], John Gibbs, Sr., [the plaintiff’s father] asked him if he thought his brother Charles Cousins might sell part of the 150 acre tract at issue and proposed that if so Gibbs would proposed that Robert Cousins be one of the people appointed to determine its value. Robert Cousins added that he had often heard Charles Cousins say he had paid the quitrents on the now disputed land. He could not recall how long he had been doing so, but “verily believes many years before the said Gibbs intermarriage with the said Mary his now wife.” He added “that it was publicly talked of and generally known long before the said Gibbs intermarriage with his wife.” Finally, he offered that he “heartily believes” Gibbs knew Charles Cousins had been promised the land and that he was in possession of it.

Thomas Dyer – Henrico/Chesterfield County neighbor of Thomas Webster II[23] testified that since John Gibbs married Mary Webster [1741] and since the death of Thomas Webster II [1748] Dyer was with John Gibbs, Jr. [plaintiff] who told him he wanted to buy some land in Amelia County. Dyer testified that Gibbs advised him “very strenuously” to talk to Charles Cousins and try to buy the disputed land. Dyer added that he had often heard Thomas Webster II say that the reason “he did not intend to give Gibbs and his wife a proportional part of his estate was owing to Gibbs affronting him greatly and cohabitating with the said Gibbs’s wife’s sister after intermarriage.”

James Old – Amelia County neighbor of Peter Webster and Thomas Webster III[24] testified that in 1747 – long since Charles, Jr. and Rosamond (Webster) Cousins married – that he heard a conversation between Thomas Webster and Charles Cousins, Jr. where Webster told Cousins that “he knew very well he had given him a piece of land lying in Amelia County joining the land of Peter Webster at the time he was married to his daughter.” Dyer testified that Webster also mentioned that Cousins’ father had previously expressed that he was “apprehensive he [Webster] would not convey it [the land] to him” but that Thomas Webster said, “you know I have had the land laid off for you & please God I live and am able to get to Amelia Court next, I will make you a conveyance of it.” He added that Webster said that he had devised the land to Cousins by his will. Finally, Dyer stated that he “believes Webster never was in a state of health afterward to get to Amelia Court.”

George Cousins – brother of defendant Charles Cousins, Jr.[25] testified that he was about 36 years of age (b.c. 1720) and that in about 1736 – the week before Charles Cousins married Thomas Webster’s daughter [Rosamond] – Webster was at Charles Cousins’ father’s house. His father was Charles Cousins, Sr., the older half-brother of Thomas Webster II. He stated that Webster needed to go to a blacksmith and that he showed him the way. Cousins recalled that Webster told him that he expected his brother [Charles Cousins, Jr.] would marry his daughter [Rosamond] but that he understood that Charles, Sr. objected to the match thinking Webster’s circumstances would not allow him to give “his daughter a fortune adequate to what this deponent’s brother [Charles, Jr.] should have.” George Cousins further testified that Webster told him that his father “should have no objection to the match for that he would give his daughter 150 acres of land lying on the Gully Branch in Amelia County joining his son Peter’s land and would give her everything for her advancement that he could possibly spare.” He added that the night after the marriage of Charles Cousins and Rosamond Webster, her father told several people that he had given the aforesaid land to his daughter, but that he had now given it to her husband. Finally, George Cousins offered that some years earlier Webster told him he would “never give John Gibbs any part of his estate” but that he would “be all the prejudice to him he possibly could for that he had behaved very inhumanely in marrying one of his daughters and got another of them with child.”

Humphrey Trailor – brother-in-law of defendant Charles Cousins, Jr.[26] – said that sometime after the marriage of Charles Cousins and Rosamond Webster, but before the marriage of John Gibbs and Mary Webster, Thomas Webster II told him he had given Charles Cousins a piece of land in Amelia County joining the land of his son Peter Webster. He added that Webster told him that his son Peter preferred he give Charles Cousins the same quantity of land in Henrico County, but that he had already given the Amelia tract to Cousins.

William Belcher – Henrico/Chesterfield County neighbor of Thomas Webster II[27] – said the night Charles Cousins married Rosamond Webster, Thomas Webster told him he had given Charles Cousins 150 acres on Gully Branch in Amelia County adjoining his son Peter Webster.

Which testimony can we believe?

Thomas Webster II was obviously someone who spoke often – and to seemingly everyone – about the entire situation over a long period of time. Given that, I find it implausible that defendants Peter Webster, Thomas Webster III and Charles Cousins “never knew or heard of Thomas Webster promising anything to John Gibbs.” In his 1738 will, Thomas Webster II clearly left land to daughter Mary – although in Henrico County rather than in Amelia County. Mary Webster was still single at the time. Three witnesses asserted that Thomas Webster II had given John Gibbs his choice of land in Henrico or in Amelia and that Gibbs chose Amelia because it was next to his father’s land (which he would eventually inherit).

In both his 1738 and 1747 wills, sons Peter and Thomas were made co-executors. But in 1747, he added Col. William Kennon as a “superadvisor” to his will (not to his sons). If Peter Webster and Thomas Webster were qualified in 1738, why did Thomas II feel the need to add Kennon? Thomas Webster II appears to have known that there would be trouble after his death. Several defense witnesses testified that Thomas Webster II had promised the disputed land to Charles Cousins when he married Rosamond Webster about 1737/8. The testimony was very detailed and specific.

Clearly Thomas Webster II intended to leave land to his daughter Mary (Webster) Gibbs,but decided not to do so after John Gibbs had an affair with Mary’s unnamed sister that produced a child. Gibbs purportedly even “cohabitated” with the sister at some point. While she is unnamed the sister seems to be Ann Webster of whom I could find nothing beyond these records.

It’s interesting that none of Thomas Webster II’s daughters testified. One would think that Rosamond (Webster) Cousins, Mary (Webster) Gibbs and Ann Webster would have been on the witness list. It also seems strange that Mary (Webster) Gibbs was punished for her husband’s actions. I have read wills where sons-in-law were excluded. Usually, by putting the daughter’s portion in trust for her and then her children. Ann Webster – the presumed sister who bore a child by Gibbs was not punished – at least in her father’s will.

Genealogical Gleanings from a Chancery Suit

Chancery suits can be a great resource for genealogical information – aside from the sometimes salacious details. In this case Judith Webster said that Rosamond Webster and Charles Cousins were married about 1737 while George Cousins said it was “about 1736.” Most likely they were married in 1738 or 1739. Rosamond was styled Rosamond Webster when her father wrote his 27 October 1738 will. In fact, all four daughters were styled Webster in the 1738 will; therefore, they were all almost certainly unmarried.

From John Gibbs, Jr. we learn that he married Mary Webster “about the month of July 1741” so the two Webster daughters were probably only married about 2-3 years apart.

We learn of the existence of Judith (Cousins) Webster. She was likely married to either Peter of Thomas III. Neither Peter’s 1774 will nor Thomas III’s 1785 will mention a wife at all, meaning that their wives predeceased them. Neither brother sold land that included a dower waiver by a wife. I could find no deed or will by an in-law or grandparent naming Peter or Thomas Webster or any of their children.

The Outcome

While there is no record of the outcome of the chancery suit in the file, it is evident that the Gibbs did not prevail. In his 1774 Amelia County will, Peter Webster left “150 acres bought from Charles Cousins” to his son Peter, Jr. who was already living on the land.[28]

Epilogue

The child born Thomas Webster II’s unnamed daughter by John Gibbs was probably born about 1746. Isaac Garrott testified in the chancery suit that “about 1745 after Gibbs intermarriage to Mary Webster and before the affront given by him to the said Thomas Webster.” The child was seemingly born by the time Thomas Webster wrote his 10 December 1747 will and disinherited John & Mary (Webster) Gibbs. I could find a single record pertaining to this child. No Webster (checked Gibbs too) child was bound out to learn a trade or had a guardian appointed in either Amelia or Chesterfield County. I also checked Amelia and Chesterfield and wills and deeds, but found no stray Webster (or Gibbs) that could have been this child. I also found no record what became of Thomas Webster II’s only unmarried daughter Ann Webster, perhaps the mother of Gibbs child.

[1] Amelia County, Virginia Chancery Cause 1757-008; Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=007-1757-008 ; accessed 23 March 2023

[2] Warner, Pauline Pierce. Orphans Court Book 1677-1739 of Henrico County, Virginia, p. 104; https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/records/item/324974-orphans-court-book-1677-1739-of-henrico-county-virginia-an-accurate-transliteration-with-index-and-explanatory-information?offset=; accessed 8 March 2023

[3] Most researchers say Prudence Gibbs was the mother of the children. I am of the opinion his first wife Mary was mother to his children and that Prudence (———-) was his second wife. Youngest child Thomas Webster III’s birth is recorded in the Bristol Parish register and lists his parents as Thomas and Mary Webster. The other children are not listed as they were born before the parish began keeping those records – in 1720. In his 1747 will, Thomas Webster II left his daughter Mary Gibbs a “leather trunk that was her mother’s.” Were Prudence, who was living when the will was written, been her mother Thomas II would have likely left the trunk to his wife and then at her death to daughter Mary. Lastly, I have found no record that suggests or confirms Prudence (———-) was a Gibbs.

[4] On 14 May 1760, Peter Webster gave his age as “about 48” in a deposition in an Amelia County, Virginia chancery case 1766-001, John Belcher vs. Jane Gordon, Etc., image 8-9 of 30; Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia.

[5] John Gibbs gave a deposition in Amelia County Chancery suit 1757-008 saying he married to Thomas Webster’s daughter (Mary) about the month of July 1741.

[6] Prudence Webster witnessed a codicil to the will of Elizabeth (Webster) Bevil, widow of Essex Bevil I, dated 15 April 1732. Her husband Thomas Webster II was a witness to the will itself, dated 14 April 1732. Elizabeth (Webster) Bevil was a daughter of Thomas Webster I and Rosamond (———-) Cousins Webster Hill. Henrico County, Virginia Colonial Wills and Deeds 1677-1737, Benjamin B. Weisiger, III, (Athens, GA: Iberian Publishing Company, 1998), p. 180

[7] Henrico County, Virginia Deed Book 1744 – 1748 [Wills, Settlements, Etc.], p. 368; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89P6-KHX4?i=282&cat=397197 ; accessed 22 March 2023

[8] Land Office Patents No. 13, 1725-1730 (v.1 & 2 p.1-540), p. 35 (Reel 12), Library of Virginia

[9] Land Office Patents No. 15, 1732-1735 (v.1 & 2 p.1-522), p. 217 (Reel 13), Library of Virginia

[10] Fry, J., Jefferson, P. & Jefferys, T. (1755) A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland: with part of Pennsylvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. [London, Thos. Jefferys] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/74693089/.

[11] A carabin was a short-barreled lightweight firearm.

[12] I have never seen a bequest to two sons for half a brass kettle each. Was it to be melted down and remade?

[13] She and her husband William Royall sold this land in 1755. Chesterfield County Virginia Colonial Deeds 1749-1756, abstracted and compiled by Benjamin B. Weisiger, III, p. 56

[14] Amelia County, Virginia Deed Book No. 5 1749-1757, p. 190; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKH-Q9N4-F?i=115&cat=282005 ; accessed 25 March 2023

[15] Thomas Deaton married Mary Gibbs, sister of John Gibbs, Jr. the plaintiff.

[16] William Purkinson was a neighbor of Thomas Webster II in Henrico/Chesterfield County,

[17] John Gibbs, Sr. was the father of the plaintiff.

[18] Elizabeth Deaton was a sister of Thomas Deaton who married Mary Gibbs, sister to plaintiff John Gibbs, Jr.

[19] Thomas Bevil was Thomas Webster II’s nephew. He was a son of Essex Bevil II and Elizabeth (Webster) Bevil. Essex Bevil I and Thomas Webster I were neighbors on Old Town Creek.

[20] Judith Webster was a daughter of Charles and Margery (Archer) Cousins and sister to Charles Cousins, the defendant in this suit who was married to Rosamond Webster. While her relationship is not stated, she is referred to as Judith Webster in her father’s 1752 will. Given her intimate knowledge of the family, I think she was either the wife of Peter Webster or Thomas Webster III, but I have not yet found any record to prove it. That said, Judith (Cousins) Webster received a bequest in her father’s 1752 will for a negro woman named Jane. When Peter Webster made his will in 1774 no wife was mentioned (likely already dead), he left his daughter Ann (Webster) Vassar a negro woman named Jane. Unfortunately, Jane is too common a name to draw a conclusion, but we add puzzle pieces where we can in hopes of adding more later.

[21] Isaac Garrott was a neighbor of Peter Webster and Thomas Webster III in Amelia County. He was a son John Garrott who was mentioned as an adjacent landowner in Thomas Webster II’s s 1734 grant “on the upper side of Smacks Creek on both sides of the Wolfe Branch.” John Garrott left a will dated 15 February 1742 and recorded 18 May 1744 in Amelia County. He left his son Isaac “the plantation I now live on.” (Amelia County, VA WB 1 (Wills 1735-1761; Bonds 1735-1754) abstracted by Gibson Jefferson McConnaughey, (Amelia, VA: Mid-South Publishing, 1978), p. 10

[22] Robert Cousins was a brother of defendant Charles Cousins and Judith (Cousins) Webster.

[23] Thomas Dyer was a neighbor of Thomas Webster II who lived on the north side of Old Town Creek in Henrico/Chesterfield County.

[24] Probably the James Old of Amelia County who was his father John Old’s executor and a defendant in an Amelia Chancery Suit brought by his 12 siblings to divide their father’s estate after their mother’s death. Amelia County Chancery Suit 1780-007, Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/full_case_detail.asp?CFN=007-1780-007#img; accessed 23 March 2023

[25] George Cousins was a brother of defendant Charles Cousins, Robert Cousins and Judith (Cousins) Webster.

[26] Humphrey Trailor [Traylor] was a brother-in-law of defendant Charles Cousins, Jr. He married Elizabeth Cousins another child of Charles, Sr. & Margery (Archer) Cousins.

[27] William Belcher was a neighbor of Thomas Webster II in Henrico/Chesterfield County.

[28] Amelia County Will Book No. 2 1771-1780, p. 146; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-L9P4-XQW1?i=79&cat=275408; accessed 24 March 2023

Great lede and family story!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I love this website

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks very much!

LikeLike