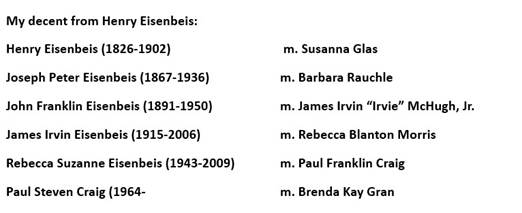

My wife and I were in Louisville, Kentucky recently with friends. While we were there, we had the opportunity to visit Cave Hill Cemetery to pay our respects to several of my ancestors who are interred there. Regular A Son of Virginia readers will recall that I have some Kentucky roots as my mother, maternal grandfather and his immediate forebearers were born and lived in Louisville. One of my ancestors interred at Cave Hill is my 3x great grandfather Heinrich “Henry” Eisenbeis (1826-1902). He is also one of my Civil War veteran ancestors – for the Union.

A Son of Bavaria

Johann[1] Heinrich Eisenbeis was born on 8 April 1826 in Münchberg, a small town in Upper Franconia, Bavaria. While Bavaria became part of Germany in 1871, it was one of dozens of independent feudal states with their own rulers during Heinrich’s early life. Ludwig I (r.1825-1848), a member of the Wittelsbach family, ruled in Bavaria.

The small town of Münchberg, where Heinrich Eisenbeis was born, is about 65 miles northeast of the City of Nuremberg. It is just south of the Town of Hof and about 15 miles from the western border of the Czech Republic. In 1995, I had the good fortune to visit Münchberg on a 10-day trip through Bavaria with my maternal grandfather James Irvin Eisenbeis (1915-2006). We visited the church where Heinrich Eisenbeis was baptized in 1826 and where his parents were married in 1814.

Of Heinrich Eisenbeis’s life in Europe, I can only pass along some family history shared by Uncle Joe. When I became interested in my family history at age 11 [1975], I wrote letters to relatives that my grandparents suggested – their siblings and cousins and, in a few cases an Aunt or Uncle. In each I asked if they could tell me anything about our ancestors and if they had any photographs of our ancestors. One of those people was my grandfather’s uncle, Joseph Jacob Eisenbeis (1890-1984), whom my grandfather called “Uncle Joe.” He lived in Louisville, and we corresponded from 1976 until shortly before his death.

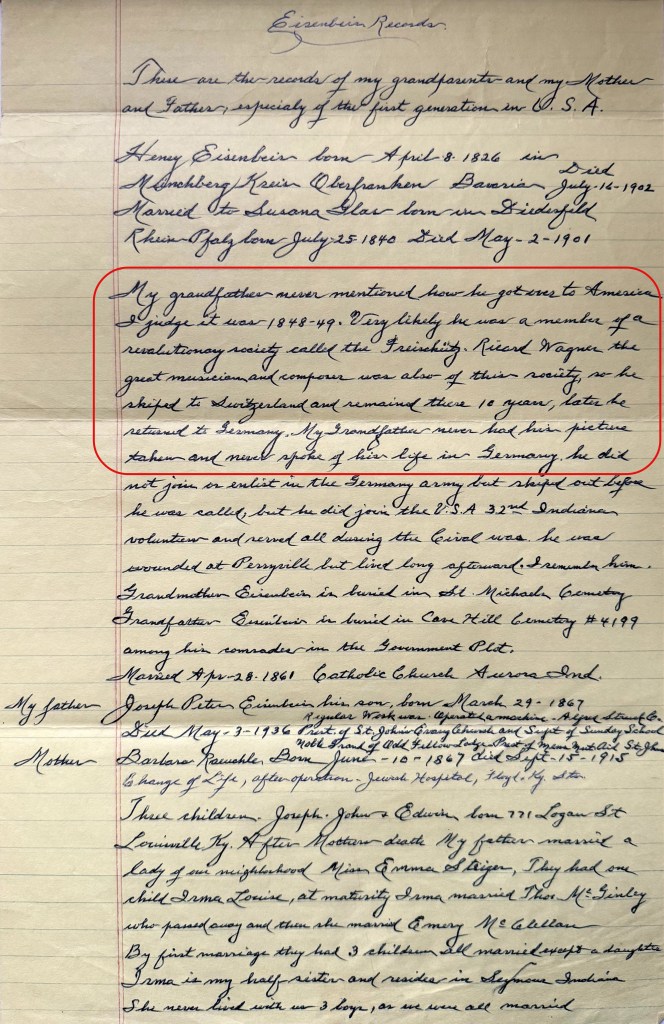

A Revolutionary Society

Uncle Joe knew his grandfather Henrich Eisenbeis personally, the latter having died when Joe was 11 years old. Uncle Joe replied to my first letter in 1976 enclosing a handwritten narrative of his grandfather. He wrote “my grandfather never mentioned how he got over to America. I judge it was 1848-49. Very likely he was a member of a revolutionary society called the Freischütz.[2] Richard Wagner the great musician and composer was also of this society[3], so he [Wagner] skipped to Switzerland and remained there for 10 years, later he returned to Germany. My grandfather never had his picture taken and never spoke of his life in Germany.”

Heinrich Becomes Henry in America

Heinrich Eisenbeis became Henry Eisenbeis when he arrived in in New York aboard the ship Atalanta on 8 May 1860.[4]

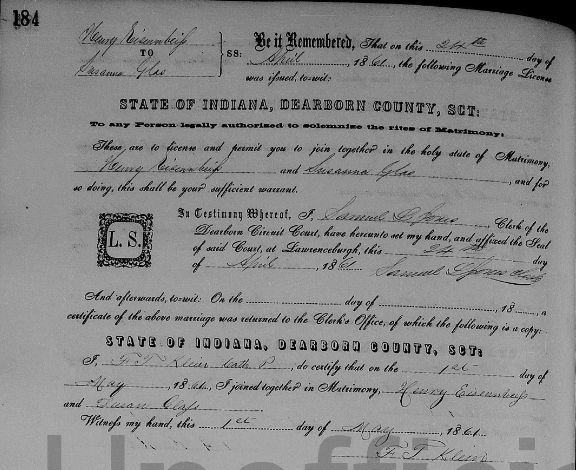

Soon after his arrival in New York, he made his way to Aurora, Indiana, where there was a large German immigrant community. On 24 April 1861, just 11 months after his arrival in the United States, he and another recent Bavarian immigrant, Susanna Glas (1840-1901), obtained a marriage license. They were married on 18 May 1861 in Aurora, Indiana.

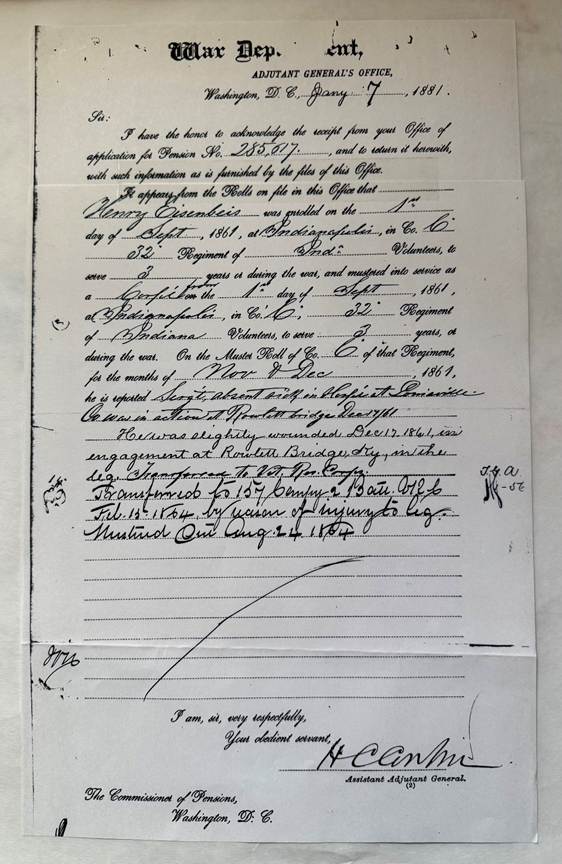

Answering A Call to Arms

Less than four months into his marriage and in response to the Indiana Governor’s call for volunteer troops, 35-year-old Henry Eisenbeis, made his way to Indianapolis, Indiana and on 1 September 1861, enlisted and was mustered in as a Corporal in Company C of the 32nd Indiana Infantry. The 32nd was often referred to as the “1st German Regiment” as nearly all of its men were German speaking immigrants. Many of the officers had military experience from fighting in Europe, which served the 32nd well in terms of training and military readiness.

In December 1861, after months of being in various camps, the 32nd Regiment found itself patrolling on the south side of the Green River near Woodsonville, Kentucky, protecting those repairing a railroad bridge vital for moving supplies. It was there at Rowlett’s Station on 17 December 1861, that the approximately 484 men of the 32nd Regiment experienced their first action of the war. The opposition included some 1,300 Confederates comprised of Mississippi Artillery, Arkansas Infantry and the 8th Texas Cavalry Regiment, known as Terry’s Texas Rangers.

The Battle of Rowlett’s Station[8]

It was about midday when a patrol from Company B of the 32nd ran into patrolling Confederates about a mile from Union positions. From there things escalated quickly. Hearing bugle calls, the rest of Company B quickly moved to support the patrol. Also entering the fray was Henry Eisenbeis’s Company C led by 1st Lt. Max Sachs, temporarily replacing a sick captain. Sachs signaled by bugling the rest of the Regiment while Company C successfully repelled a cavalry charge by Terry’s Texas rangers.

The other companies of the 32nd made their way rapidly to assist companies B and C with Lieutenant Colonel von Trebra in overall command. He ordered Companies K, G, and F on the right wing in support of Company B. Companies A and I were ordered forward to support Company C on the left wing, and finally reserve companies to the rear.

The rapidity with which the 32nd companies readied themselves seemed to unsteady some of the Confederates. But not Terry’s Texas Rangers who launched a cavalry charge. During this attack Lt. Sachs ordered Company C out of the woods into an open field with only two large haystacks for cover. The Texans quickly surrounded the company demanding their surrender, but Lt. Sachs refused. While Company C managed to repel the Texans, Lt. Sachs and three others were dead or dying and seven others were wounded.

Included among the wounded was Henry Eisenbeis who sustained a bullet wound below his left knee “immediately in front fracturing the bone.”[9] Companies A and I quickly came to their aid undoubtedly saving the living from being killed or captured.

The battle raged on for some two hours including repeated cavalry charges and hand-to-hand combat. In the end, the 32nd held the ground when the Confederates retreated as they saw Union reinforcements arriving. The Confederates reported 33 men and 50 wounded while the 32nd reported one officer (Lt. Sachs) and 10 men killed, 22 wounded and five missing.

After a visit to the hastily erected “hospital” at Munfordville, Chaplin Richard Gunter reported “I visited all the wounded today. Number one has his ear shot off, number two is minus the bridge of his nose, four or five wounded in the arms, four or five in the legs, four in the chest, one in the abdomen, another has a quantity of buckshot in his side.” Henry Eisenbeis was likely among this group.

A Wounded Warrior

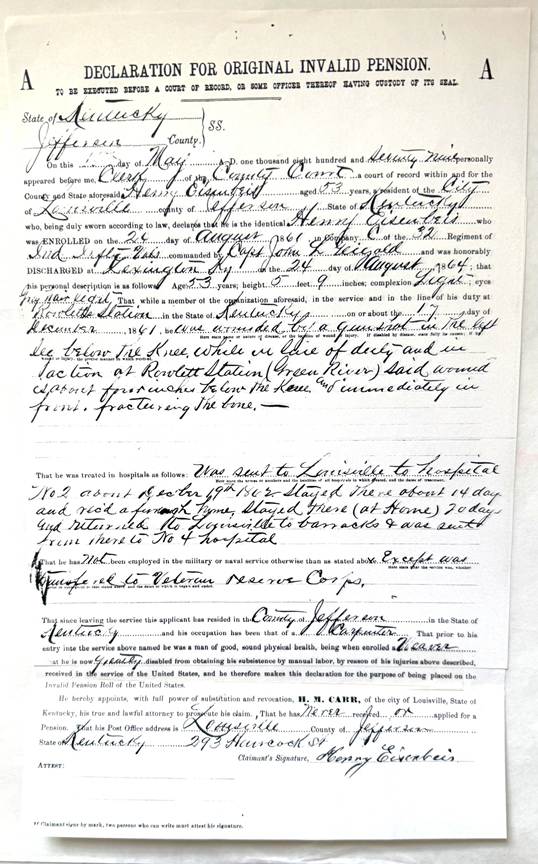

Henry’s pension application states that he “was sent to Louisville to hospital No. 2 about December 19th 1862. Stayed there about 14 days and received a furlough home. Stayed there (at home) 20 days and returned to Louisville and returned to barracks & was sent from there to No. 4 hospital.”

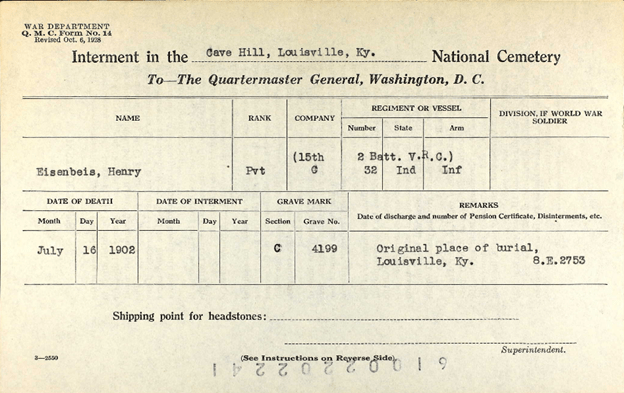

Company muster rolls indicate that Henry spent more than two years in the hospital at Louisville. On 15 February 1864, some 22 months after he was injured, Henry Eisenbeis was transferred to the 157th Company, 2nd Battalion, Veteran Reserve Corp. His three-year enlistment ended about six months later and he was mustered out of service on 24 August 1864.[10]

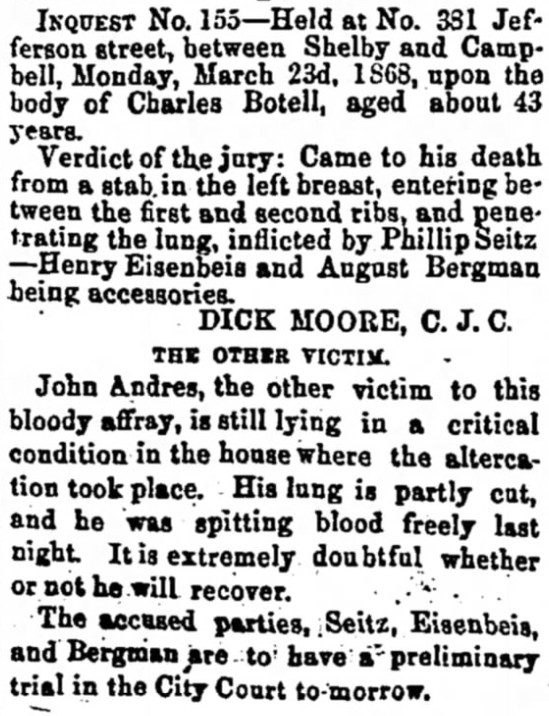

Henry Eisenbeis Arrested as an Accessory to Murder

Having spent much of the War in Louisville, Henry Eisenbeis moved his family across the Ohio River to make it their home about 1865. He and wife Susan had one son named Frederick born in February 1862. They began expanding their family welcoming sons Anton William, born in June 1865 and Joseph Peter, born in March 1867. Susan was about four months pregnant on the evening of 22 March 1868, when Henry decided to go out with friends. Between 8-9 pm, Henry Eisenbeis, August Bergman, and Philip Seitz entered Mr. Boesser’s saloon on Jefferson Street and ordered three beers. Charles Botell was sitting in the bar. August Bergman jumped up and asked Botell, “What have you to say of my wife?” To which Botell replied, “I do not know your wife.” During the tense exchange, Henry Eisenbeis and Philip Seitz went out the back door of the saloon into the alley joined shortly afterward by Bergman, Botell and a man named John Andrea. Within a few minutes, Charles Botell was stabbed and killed, and John Andrea was fighting for his life.

The following day, a coroner’s inquest was held at Boesser’s saloon with the jury meeting in the saloon’s back room. Four witnesses testified including Mrs. Boesser, two tenants living at Boesser’s named Jacob Haag and Phillip Botell (the victim’s brother) and George Miller who lived near the alley behind Boesser’s saloon. Dr. Curran noted that Botell was stabbed in “the left breast between the first and second ribs to the lung.” He added that the wound was an inch and a half to two inches long and that one of the ribs was nearly cut in two. He opined that the stab wound was the cause of death. After deliberation, the jury indicted all three men with Seitz being charged with murder and Eisenbeis and Bergman as accessories.[11]

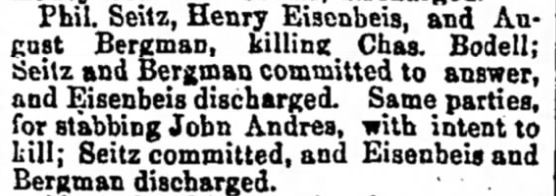

After a few continuances, the men’s preliminary hearing was held on 2 April 1868. The same four witnesses from the coroner’s inquest testified as did John Andrea, the other victim who had recovered enough to testify that Seitz had stabbed Botell four times with a butcher knife. He further testified that Seitz had stabbed him as well – twice in the back.[13] At the end of all of the testimony, Seitz and Bergman were “committed to answer” for the murder of Charles Botell while Eisenbeis was discharged. Seitz was also committed to answer for the stabbing of John Andrea with both Eisenbeis and Bergman being discharged.[14] Ultimately, Seitz was convicted of manslaughter.[15]

A Carpenter’s Life in Louisville

This was the only known misadventure in Henry’s life in Louisville. Susan gave birth to their first daughter named Louisa in August 1868, but sadly she died in November. More children followed including Theresa, born in 1870, John, born in 1871, Martin, born in 1873, Mary, b. 1875, Anna, b. 1877 and Philip in 1880.

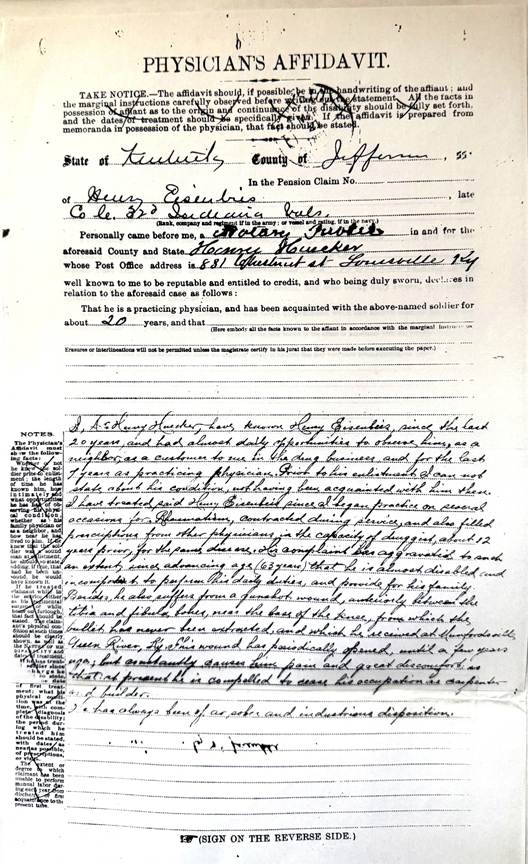

In May of 1879, when Henry Eisenbeis filed for his invalid pension, an accompanying physician’s affidavit reported that he had treated Henry for “rheumatism, contracted during service” for some 12 years and that Henry’s “complaint has aggravated, to such an extent, since advancing age (63 years) that he is almost disabled.” The doctor added “Besides, he also suffers from a gunshot wound, anteriorly between the tibia and fibula bones, near the base of the knee, from which the bullet has never been extracted, and which he received at Munfordsville, Green River. This wound has periodically opened, until a few years ago, but constantly causes him pain and great discomfort, so that at present he is compelled to cease his occupation as carpenter and builder.”

Interestingly, in a communication from the War Department dated 7 January 1881, Henry’s wound was described as “He was slightly wounded Dec 17, 1861 in engagement at Rowlett’s Bridge, Ky, in the leg.”

In 1880, the year after he filed for a pension, the census for Louisville, Kentucky includes Henry Eisenbeis[16], age 54, working in a carpenter shop, living on Bremer Street with wife Susan, 40 and children William, 15, Joseph, 14, Teresa, 10, John, 8, Martin, 7 and Mary, 5. All the children except Mary were attending school.[17]

In 1900 Henry, 73 and Susan, 59, were living in at 1116 Wickliffe Avenue in Louisville, in a house they owned and that Henry built. Henry was listed as being a “house carpenter” and their sons living with them were Fred, 32, also a house carpenter and Phillip, 19, a machinist. The census noted that they had 10 children, seven of whom were living.[18] In addition to daughters Louisa, who died in 1868, and Anna, who died in 1878 at just a year old, they lost 14 year old Mary in 1889.

Susanna “Susan” (Glas) Eisenbeis died of consumption on 2 May 1901 at the age of 59 and was interred at St. Michael’s Catholic Church in Louisville, Kentucky.[19] Henry Eisenbeis died on 16 July 1902 at the age of 76 and was interred alongside his fellow soldiers at Cave Hill Cemetery.

Mysteries Endure

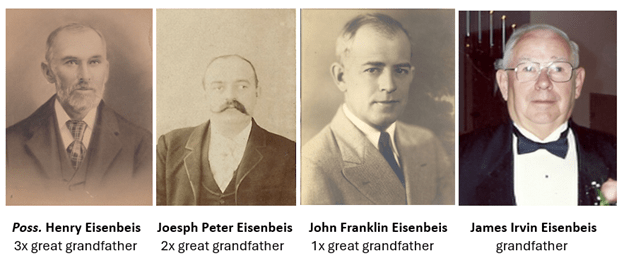

I have been unable to find anything about Henry Eisenbeis in Europe. Closer to home another mystery endures. After my grandfather died in 2006, I found a charcoal portrait in his office closet. Charcoal portraits were popular from the 1880s into the early 1900s. I have photographs of 14 of 16 2x great grandparents and several 3x great grandparents so I know who it is not. I think it is Henry Eisenbeis. The style of clothing he is wearing – a sack suit, waistcoat (vest), high collared shirt and tie and his beard – suggests 1880s when Henry was in his 60s. The only description of Henry Eisenbeis is from his 1879 pension application, which states he had “light eyes” and “light gray hair.” Seems to fit the bill. The most compelling evidence, however, is the comparison to my other Eisenbeis ancestors. Notice anything similar? Yep – all were follicly challenged. Notice that they all parted their hair on the left side as well. What do you think?

[1] “Boys commonly were baptized with the first name Johannes (or Johann, often abbreviated Joh). German girls were baptized Maria, Anna or Anna Maria. This tradition started in the Middle Ages. The second name, known as the Rufname, along with the surname is what would be used in marriage, tax, land and death records.” Haddad, Diane. German Naming Traditions Genealogists Should Know, Family Tree Magazine, ©2025 Yankee Publishing, Inc., An Employee-Owned Company; https://familytreemagazine.com/names/first-names/german-naming-traditions/

[2] Freischütz” in German tradition denotes a marksman who gains infallible bullets through a pact with demonic forces, a folklore motif popularized by Weber’s 1821 opera Der Freischütz; https://www.britannica.com/topic/Der-Freischutz

[3] Wagner was a member of a revolutionary society called the “Fatherland-Union” and did live in exile in Switzerland; The Social Democrat, Vol. VI No. 7 July 1902, pp. 202-205, Public Domain: Marxists Internet Archive (2007), https://www.marxists.org/archive/montefiore/1902/07/wagner.htm

[4] New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957; Ancestry.com

[6] Indiana, Marriage Certificates, 1917-2005, Indiana Archives and Records Administration; Indianapolis, IN, USA; Indiana State Board of Health Marriage Certificates, 1816-1956, Ancestry.com

[7] Terre Haute Star, Sat, Aug 10, 1861 ·Page 2, newspapers.com

[8] Adapted from Indiana’s German sons : a history of the 1st German, 32nd Regiment Indiana Volunteer Infantry : baptism of fire: Rowlett’s Station, 1861, by Michael A Peake, (Indianapolis: Max Kade German-American Center, 1999.

[9] Henry Eisenbeis, Declaration for Original Invalid Pension (May 1879)

[10] U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Pensions, Report on Henry Eisenbeis Civil War Service, dated March 1900

[11] The Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 24 March 1868, page 2; newspapers.com

[12] The Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 24 march 1868, page 2; newspapers.comD

[13] The Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 3 April 1868, page 2; newspapers.com

[14] The Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), 4 April 1868, page 2; newspapers.com

[15] The Louisville Daily Courier, 18 May 1868, p. 3; newspapers.com

[16] erroneously listed as Henry Assanberg

[17] 1880 U.S. Census, Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky, p. 439, House No. 76, Dwelling No. 155, Family No. 210; Ancestry.com

[18] 1900 U.S. census, Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky, p. 156, House No. 1116, Dwelling No. 146, Family No. 160; Ancestry.com

[19] Kentucky Death Records, 1852-1953, Online publication – Provo, UT, USA: The Generations Network, Inc., 2007.Original data – Kentucky. Kentucky Birth, Marriage and Death Records – Microfilm (1852-1910). Microfilm rolls #994027-994058. Kentucky Department for Libraries and Archives, Frankfort Ancestry.com

[20] U.S. National Cemetery Interment Control Forms, 1928-1962; Ancestry.com