In 1757, my 6x great-grandfather Robert Vaughan I (c.1710-c.1779) and his brother Abraham Vaughan (1721-c.1795) served as interpreters and guides during the French & Indian War (1754-1763). Both men were sons of Nicholas and Ann (———-) Vaughan of Prince George County, Virginia. In 1757, Robert Vaughan was living in Amelia County having settled there by 1735. Abraham Vaughan left Amelia County for Lunenburg County [created 1746] about 1749.[1]

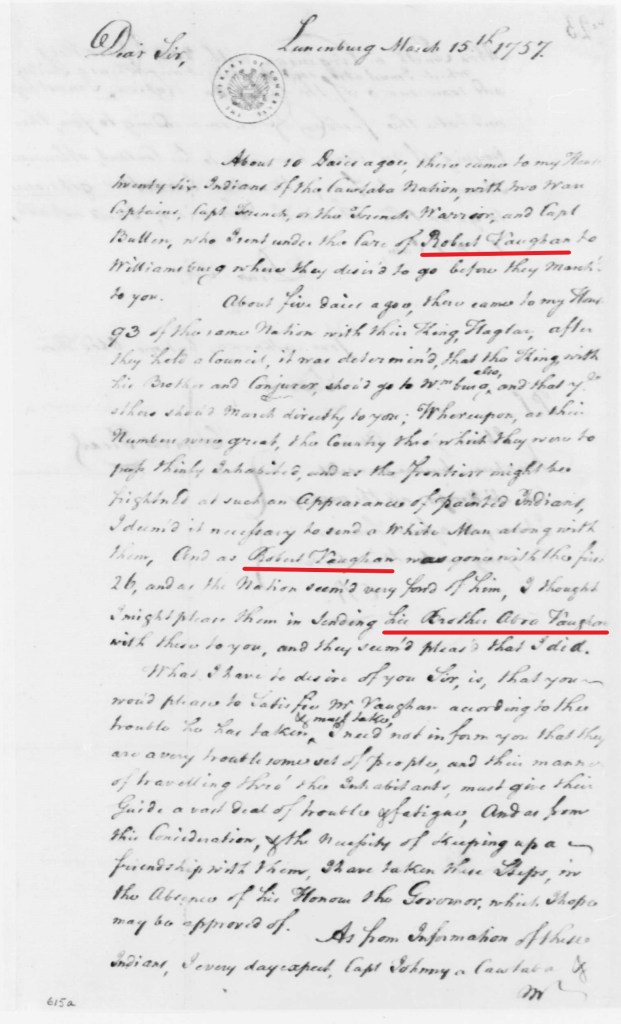

In a letter dated 15 March 1757 from Clement Read[3] of Lunenburg County to Col. George Washington, commander of the Virginia Regiment then at Winchester, Virginia, it is revealed that approximately 10 days earlier, 26 members of the Catawba tribe[4] arrived at Read’s house who he sent “under the Care of Robert Vaughan to Williamsburg where they desir’d to go before they March’d to you.”

Read further advised Washington that about five days after the first party arrived, a larger group of 93 Catawba arrived at his house in Lunenburg including their Chief “King Haglar.”[5] A smaller group including the chief were going to Williamsburg while the rest were going to Winchester to see Washington. Read wrote “as their Numbers were great, the Country thro’ which they were to pass thinly Inhabited, and as the Frontiers might be frightned at such an Appearance of Painted Indians, I deem’d it necessary to send a White Man along with them, And as Robert Vaughan was gone with thee first 26, and as the Nation seem’d very fond of him, I thought I might please them in sending his Brother Abraham Vaughan with these to you, and they seem’d pleas’d that I did.”

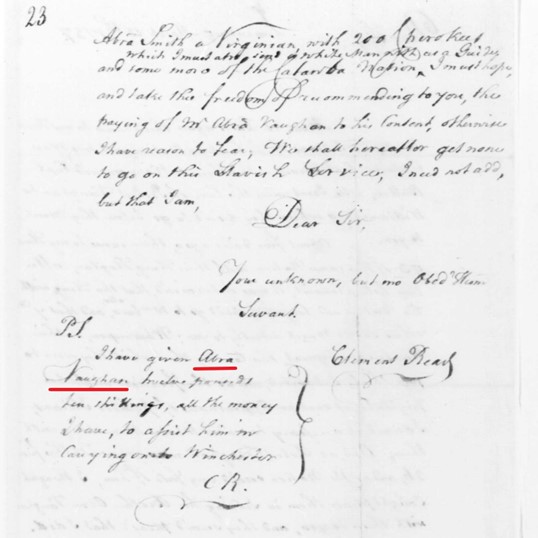

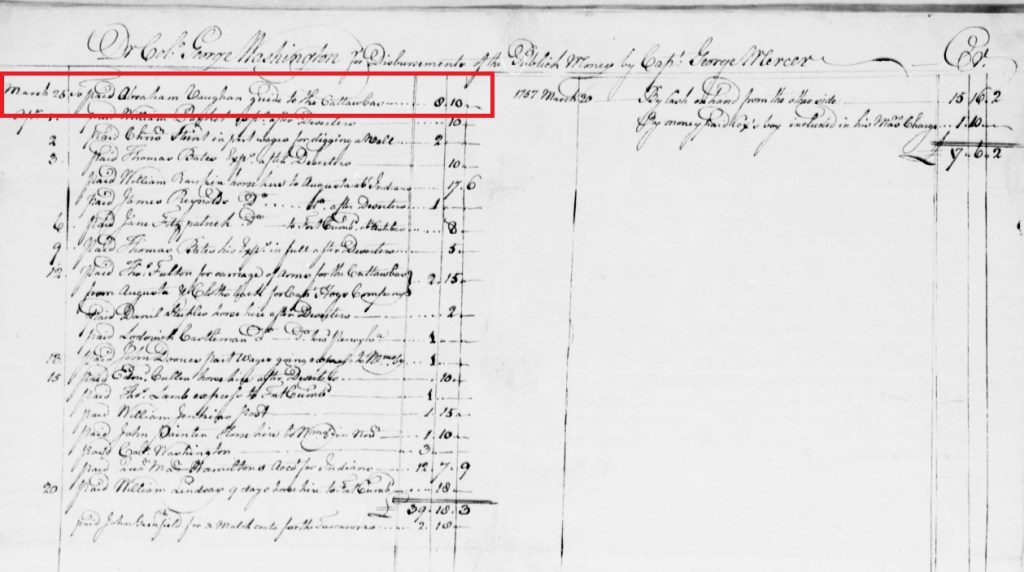

Read then asks Washington pay Abraham Vaughan “according to thee trouble he has taken & must take, I need not inform you that they are a very troublesome set of people, and their manner of travelling thro’ the Inhabitants, must give their Guide a vast deal of trouble & fatigue.” He added “I must hope, and take the freedom of recommending to you, the paying of Mr Abra Vaughan to his content, otherwise I have reason to fear we shall hereafter get none to go on this Slavish Service.” The letter closes with a postscript “P.S. I have given Abra Vaughan twelve pounds ten shillings, all the money I have, to assist him in Carrying on to Winchester.”[6] On 25 March 1757, George Mercer sent George Washington an expenditures report, which included £8.10 to “Abraham Vaughan guide to the Cattawbas” netting Abraham’s £21 for his service.[7]

The French & Indian War – What was happening here?

The French & Indian War was fought between North American British and French colonists and their Native American allies[8] over land – at the time what was known as the Ohio Country.[9] The North American war became part of the wider Seven Years War [1756-1763] between Great Britain and France. George Washington was commissioned a major of the Virginia militia in 1753, but by 1755 was colonel and commander of the Virginia Regiment. Responsible for directing the defense against French and Indian raids on the frontier, he was based in Frederick Town [Winchester, Virginia]. Virginian’s living in the sparsely populated frontier Valley had experienced such raids as early as 1752.[10] The British also had allied native tribes on their side including the Catawba Nation who had signed a treaty with the British in Spring 1756..[11] The Catawba fought with Col. Washington during the winter of 1756 and into the spring of 1757.[12] After this fighting the Catawba returned to their lands in the Carolinas for a brief time and were now coming back to Virginia to meet with colony leaders.

The Williamsburg Meeting – Robert Vaughan’s Service

Robert Vaughan escorted the group of 26 Catawba including their chief King Hagler to Williamsburg – then the capital of Virginia – to meet with the colony’s leaders. On 18 March 1757, the council met and it’s minutes include a reference to my ancestor Robert Vaughan I (c.1710-c.1779):

“The Council being informed that the potent Warriour Hagler King of the Catawba Nation was arrived near Town with two of his great Men, Peter Randolph Esqr. by Desire of the Board withdrew and proceeded in a Coach to meet them, and having accompanied them to the Capitol, they were introduced into the Council Chamber with six and twenty more of the Catawbas, who came here the Wednesday before, and Robert Vaughan Interpreter; King Hagler, after he and his Attendants had taken all the Council by the Hand, and their Seats, expressed himself to the following Purpose

“Tho I am grown old, my Heart is so affected by the Relation of the horrid Murders and Depredations committed upon my Brethren the English by their cruel Enemies that I have undertaken this Journey with a Resolution of doing everything in my Power towards extirpating them from the face of the Earth. The many and substantial Tokens I have received of the Affection of the English for me and my People, I have the deepest and most grateful Sense of, and shall ever preserve them treasured up in my Mind. I have left between eighty and ninety of the Warriours who came with me upon the Frontiers, and am come to this Town out of an ardent Zeal to see and serve you, to hear your Talk, and to learn if you have anything to propose for our mutual Good.” He then presented to the President a String of Wampum. The President answered, he heartily rejoiced to see him, was perfectly convinced of his Love for the English, intreated him to come to the Council Chamber tomorrow when he should return a more full and particular Answer to his affectionate Speech. After shaking Hands again they departed well pleased.”

The following day “King Hagler appearing in the Council Chamber with the rest of the Catawbas, and Interpreter, and being seated, the President [William Fairfax] spoke as follows Sachems and Warriours of the brave Catawbas,

“We rejoice to see you and to hear your good Talk, and we are not a little pleased to hear that you have brought a great Number of Warriours to our Assistance. Your due Observance of the Treaty held with our Commissioners last Year, is a proof of your Fidelity to the great King your Father, and of your Regard for us his Children. And you may be assured, we shall on every Occasion endeavour to shew you the Respect due to great Warriours and faithful Friends We very much lament the Loss of your brave Men who were killed this Winter near Fort Du Quesne; but the Chance of War is uncertain, and as our Friends fell in the Bed of Honor, nobly disdaining to be taken Prisoners, let us wipe away our Tears and think of nothing but Revenge.

For that purpose we give you this Hatchet, and desire that you will hold it fast, never ceasing to use it till you have painted it with the Blood of our Enemies. You have made us acquainted with your Wants, and we shall take Care to supply you with Guns and everything necessary for war. Our Governor is now at Philadelphia attending Business of the greatest Importance both to you and us From him you may expect at your Return from War, a Reward equal to your Services. By the Governor’s Absence we are quite destitute of Wampum, and therefore hope you will excuse our not giving you any at this Time.

King Hagler replied he was perfectly satisfied now he had heard our friendly Talk, and should proceed chearfully to War with strong Hopes of Success; that they were in no Expectation of receiving Wampum at this Time, they only desired to be furnished with Cloaths, Arms, and Ammunition, were in Haste to be dispatched, and should wait till their Return for Presents proportioned to their Services.

The President assuring them they should be delayed no longer than was absolutely necessary, and he, and the Council embracing them all, they marched orderly out of the Council-Chamber with a joyful Countenance.”[13]

The Role of the Interpreter

Interpreters were indispensable in complex and often tense interactions between colonial settlers and Native American tribes during the French and Indian War. They were responsible for translating not just the language, but also the cultural nuances between the English and Native Americans. This would have required a deep understanding of both languages and cultures. Interpreters also functioned as mediators during conflicts helping to resolve misunderstandings and disputes. Their role was essential in preventing conflicts from escalating and in maintaining a level of trust between the parties involved.[14] Interpreters often accompanied military and diplomatic missions. They helped leaders negotiate treaties, alliances, and trade agreements. Lastly, interpreters could provide colonial leaders valuable insight into Native American strategies, movements and intentions.[15]

How did the Vaughan brothers become interpreters and guides?

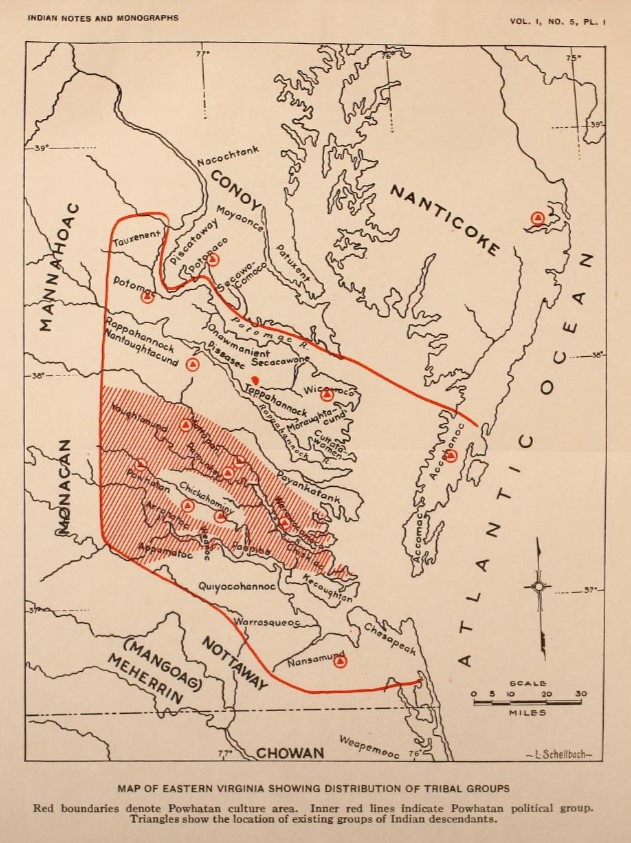

While I cannot say with any certainty how Robert Vaughan [c.1710-c.1779] and Abraham Vaughan [1721-c.1795] came to be interpreters, it is evident that Native Americans were a part of their lives. They grew up on Hatcher’s Run in Prince George County, Virginia.[16] The Weyanoke tribe’s main settlement was in Charles City County and a large secondary settlement was at the head of Powell’s Creek in Prince George County. Other tribes in the vicinity included the Pamunkey, Chickahominy, Nansemond, Nottoway and Meherrin.

Robert and Abraham’s father Nicholas Vaughan (c.1685-c.1737) grew up in Charles City County. He was a son of William Vaughan [c.1625-c.1694], whose land abutted the both the Appomattox River and the Northern Main Branch of the Blackwater Swamp [present day Prince George County]. He likely grew up with a Native American boy named Will in his household. When Nicholas Vaughan’s father made his will in 1692, he bequeathed the boy Will to his youngest son:

“I give to my son Nicholas one musket I bought of Henry Chemnis [his neighbor Henry Chumings] and after my wife’s death and my own, one Indian boy called Will for fifteen years. If the said Indian boy serves the said term [he is] to be free and that my son Nicholas give the said Indian boy one gun at the expiration of his time and let him have what ground he can lend out of his part of my land.”

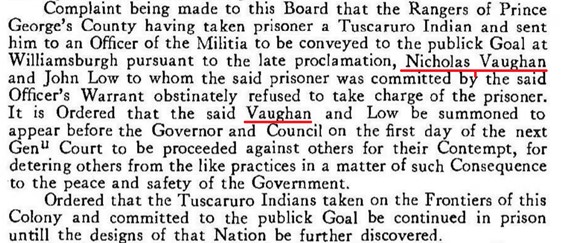

On 10 June 1712, at a meeting of the Virginia Executive Council held in Williamsburg, a complaint was presented by the Prince George County rangers against Nicholas Vaughan and John Low, jailors, who “obstinately refused to take the prisoner” who was a member of the Tuscarora tribe. They were “ordered to appear before the Governor and Council . . . to be proceeded against others for their Contempt, for deterring others from the like practices in a matter of such Consequence to the peace and safety of the Government.”[17] This occurred during the Tuscarora War (1711-1715), which primarily took place in North Carolina, but also included some activity on the Virginia frontier. There is no further mention of Nicholas Vaughan or John Low in future meeting minutes.

You Never Know How You Might Find Genealogical Proof

This connection to the French and Indian War, George Washington, King Hagler and the Catawbas is fascinating. But more important is that I finally found a record that proves Robert Vaughan is the son of Nicholas Vaughan! Knowing it is one thing, but proving it is another. Nicholas and Ann Vaughan lived in Bristol Parish where birth and baptism records began in 1720[18]. Four of Nicholas and Ann’s children are listed:

Luis [Lewis], son of Nico: & Ann Vaughan born 20 February 1719 baptized 7 June 1722

Abra [Abraham], son of ditto born 16 March 1721, baptized 7 June 1722

Eliza [Elizabeth], daughter of Nicholas and Ann Vaughan born 18 April 1727

Nicolas, son Nicolas and Ann Vaughan born 20 February 1728

Fact: Abraham Vaughan is a son of Nicholas & Ann (———-) Vaughan.

On 9 December 1738 the Amelia County, Virginia Court appointed Richard Hicks/Hix the guardian of Abraham Vaughan “infant son of Nicholas Vaughan.” Infant meant “under age” and, in fact, Abraham was 17 years old at the time. Hicks required bond of £20 indicates Nicholas Vaughan left a small estate.[19]

Fact: Nicholas Vaughan’s orphan son Abraham lived in Amelia County.

On 12 January 1746, Abraham Vaughan received a land grant in Amelia County, Virginia for 525 acres on the lower side of Saylors Creek.[20] On 21 December 1750, Abraham Vaughan of Lunenburg County sold this 525 acre tract in Amelia County to his brother Thomas Vaughan of Amelia County. Abraham’s wife Mary waived her dower right. The deed was witnessed by John Turner [brother-in-law m. to sister Mary ], Lewis (X) Vaughan [brother] and Martha (X) Vaughan [sister-in-law Robert’s wife].[21] On 5 September 1749 Abraham Vaughan received a land grant in Lunenburg County for 400 acres beginning at John Twitty’s corner on a branch of the second fork of Lickinghole.[22] He also began paying personal property tax [tithe] that year.[23]

Fact: Abraham Vaughan moved from Amelia to Lunenburg County in 1749

The 15 March 1757 letter from Clement Read of Lunenburg County to Col. George Washington states “I deem’d it necessary to send a White Man along with them, And as Robert Vaughan was gone with thee first 26, and as the Nation seem’d very fond of him, I thought I might please them in sending his Brother Abraham Vaughan with these to you, and they seem’d pleas’d that I did.”

Fact: Robert Vaughan and Abraham Vaughan were brothers.

Conclusion: Robert Vaughan (c.1710-c1779) of Amelia County, Virginia was a son of Nicholas Vaughan (c.1625-c.1694) of Prince George County, Virginia

Other Vaughan family posts available through A Son of Virginia:

William Vaughan (c.1625-c.1694) of Charles City County, Virginia (my 8x great grandfather)

https://asonofvirginia.blog/2023/01/18/william-vaughan-c-1625-c-1694/

Nicholas Vaughan (c.1685-c.1737) of Prince George County, Virginia (my 7x great grandfather)

https://asonofvirginia.blog/2023/02/06/nicholas-vaughan-my-7x-great-grandfather/

Robert Vaughan (c.1710-c.1779) of Amelia County, Virginia (my 6x great grandfather)

Robert Vaughan II (c.1736-c.1805) of Amelia and Nottoway Counties, Virginia (my 5x great grandfather)

Robert Vaughan III (c.1770-c.1819) and Sarah (Truly) Craddock Vaughan (c.1770-1839) (my 4x great grandparents)

[1] On 5 September 1749 Abraham Vaughan received a grant in Lunenburg County for 400 acres and also began paying personal property tax (tithe) the same year.

[2] Fry, J., Jefferson, P. & Jefferys, T. (1755) A map of the most inhabited part of Virginia containing the whole province of Maryland with part of Pensilvania, New Jersey and North Carolina. [London, Thos. Jefferys] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/74693166/.

[3] Clement Read was a leader in the defense of Virginia’s southwestern frontier during the war. He served as a Lieutenant in the Lunenburg County Militia and served as one of the county’s Burgesses.

[4] The Catawba are part of the Siouan language family, which takes its name from the Sioux Indians of the northern Plains. Included are subfamilies of Catawba and Siouan Proper. The Catawba, who presently live on a small reservation in York County, South Carolina, were for many years a powerful refuge community; as such, they were later joined by linguistic relatives from North Carolina and, eventually, Virginia; Rountree, Helen. Languages and Interpreters in Early Virginia Indian Society. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/languages-and-interpreters-in-early-virginia-indian-society.

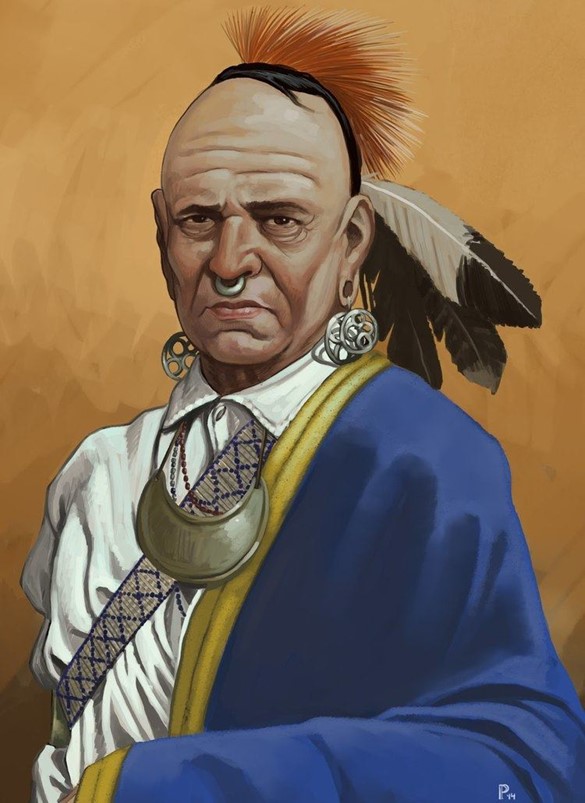

[5] “King Hagler” was a prominent chief of the Catawba Native American tribe from about 1751 until his death in 1763. Under King Hagler the Catawba supported the British in the French and Indian War. They fought with Colonel George Washington in the winter of 1756 and the spring of 1757; McCullough, Anne M. South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies; https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/hagler/

[6] (1757) George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: Clement Read to George Washington. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw442521/.

[7] (1757) George Washington Papers, Series 4, General Correspondence: George Mercer to George Washington, Expenditures from December 21, 1756. [Manuscript/Mixed Material] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/mgw442522/.

[8] The British colonists were supported at various times by the Iroquois, Catawba, and Cherokee tribes, and the French colonists were supported by Wabanaki Confederacy members Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, and the Algonquin, Lenape, Ojibwa, Ottawa, Shawnee, and Wyandot (Huron); https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_and_Indian_War

[9] The “Ohio Country” referred to a loosely defined a region of colonial North America west of the Appalachian Mountains and south of Lake Erie.

[10] Magill, Barbara. French & Indian War Along Cedar Creek and in the Shenandoah Valley, National Park Service; https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/french-and-indian-war-shenandoah-valley.htm

[11] A Treaty: Between Virginia and the Catawba and Cherokee, 1756, The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Jan., 1906, Vol. 13, No. 3, (Jan., 1906), pp. 225-264, Virginia Historical Society; https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/4242744.pdf

[12] McCullough, Anne M. South Carolina Encyclopedia, University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies; https://www.scencyclopedia.org/sce/entries/hagler/

[13] Hillman, Benjamin J. Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia, Vol. VI (June 20, 1754-May 3, 1775), Richmond, VA: 1996), pp. 31-33; https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/viewer/25470/?offset=0#page=44&viewer=picture&o=info&n=0&q=

[14] Kawashima, Y. (1989). Forest Diplomats: The Role of Interpreters in Indian-White Relations on the Early American Frontier. American Indian Quarterly, 13(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.2307/1184083

[15] Rountree, Helen. Languages and Interpreters in Early Virginia Indian Society. (2020, December 07). In Encyclopedia Virginia. https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/languages-and-interpreters-in-early-virginia-indian-society.

[16] Prince George County was formed in 1703 out of Charles City County (original shire 1643).

[17] Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia Vol III (May 1, 1705 – October 23, 1721), p. 315; https://www.familysearch.org/library/books/viewer/40330/?offset=0#page=322&viewer=picture&o=download&n=0&q=Vaughan

[18] Chamberlayne, Churchill Gibson. The Vestry Book and Register of Bristol Parish, Virginia 1720-1789, published privately 1898; pp. 379-380; The Vestry Book and Register of Bristol Parish, Virginia, 1720-1789 – Google Books; accessed 17 January 2023

[19] McConnaughey, Gibson Jefferson. Deed Book I, Amelia County Deeds 1735-1743, Bonds 1735-1741, p. 96

[20] Land Office Patents No. 24, 1745-1746, p. 584 (Reel 22), Library of Virginia

[21] Amelia County, Virginia Deed Book No. 4 (1750–1754), p. 16; https://www.familysearch.org/search/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKW-MS5H-W?view=fullText&keywords=Abraham%20Vaughan&groupId=M9XL-HXP

[22] Land Office Patents No. 27, 1748-1749, p. 295 (Reel 25), Library of Virginia

[23] Lunenburg County, Virginia Tithable Lists 1748-1756, Reel 411, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

Very interesting Steve. My wife’s grandfather’s was a Haigler (Adam) and was from the area of Orangeburg, SC where there are many Haiglers.

Bill Blanton Apex, NC

>

LikeLike

Thank you, Bill. That was a cool find. We have a Vaughan reunion coming up so I’ve been doing a sting of those. Back to the Blantons soon!

LikeLike