CONTENT GUIDANCE: When I undertake a study of my Virginia ancestors, I find every source I can about a person or a group of people and find that it usually tells a story. Sometimes one record, such as a will or estate inventory tells a story by itself. Sometimes there is more. The Holland story that spoke to me is one of multigenerational debt, mortgaging enslaved men, women and children and repeated lawsuits by creditors to force their sale to collect the debt. It’s also the story of Patt and Hannah and their many descendants. This blog post explores the enslavement of men, women and children by my Holland ancestors. It contains both language and imagery many will find disturbing. It is made all the more difficult by learning about a topic through getting to know individuals and families rather than in the abstract as a background topic. Please read with care.

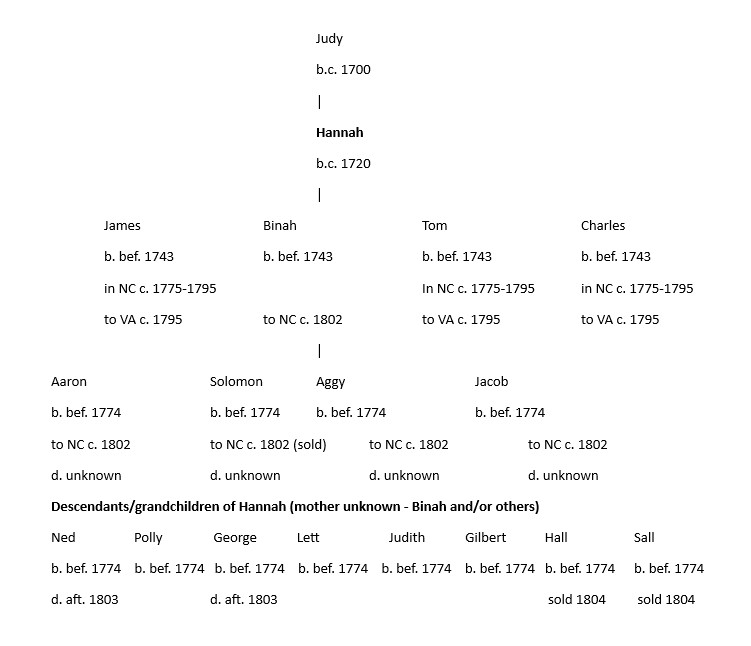

Reminder: Throughout this series I am using [Patt] and [Hannah] behind names of their known descendants.

If you missed Parts 1-3, you really should start here:

Introduction

We ended part 3 with the 1802-3 death of Dick Holland and his last will and testament wherein he appointed “my dearly beloved wife Martha Holland Doct. James Walker [Martha’s son from her first marriage to Henry Walker] and Benjamin Moore Executors” Then just like his parents, Dick Holland added “my will and dezire [sic] is that my Estate shall not be appraised.”

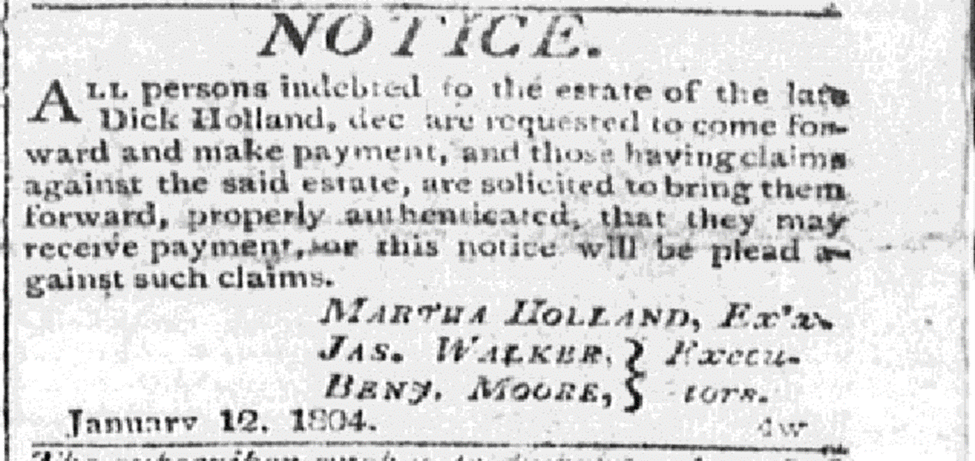

The Virginia Argus, Wednesday, Jan 18, 1804, Richmond, VA, Vol: XI, Issue: 1113, Page: 1

Martha (Jones) Walker Holland

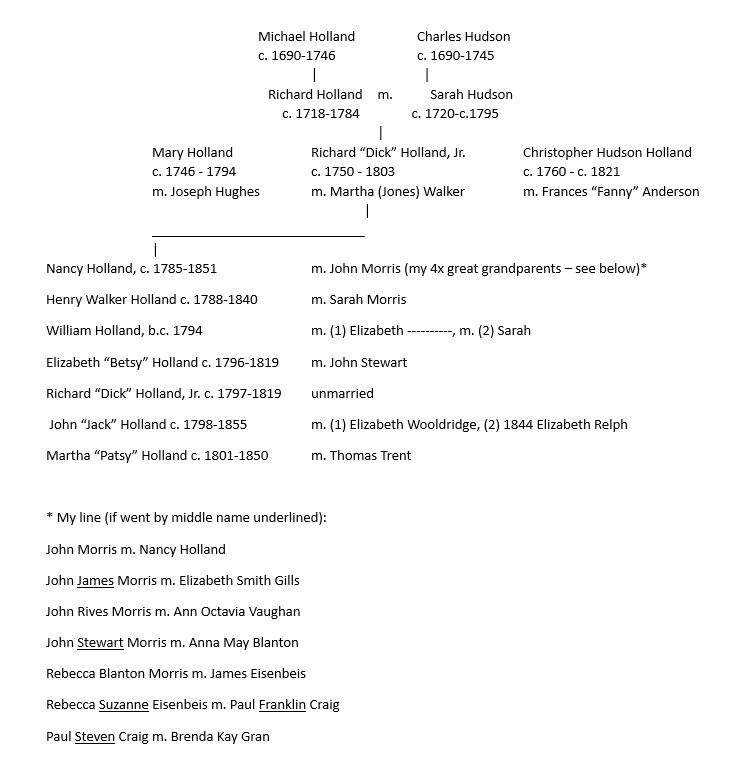

In 1803, Martha (Jones) Walker Holland found herself twice widowed. She was a daughter of William and Lucy (Anthony) Jones of Buckingham County, Virginia.[1] By her first husband, Capt. Henry Walker who was killed during the Revolutionary War, she had two children including Lucy Walker, b.c. 1776 and James Walker, b.c. 1778. Lucy Walker married Micajah Woods about 1795 and died soon after. Martha (Jones) Walker Holland’s son James Walker became a physician and lived across the Appomattox River in Buckingham County.[2] With Dick Holland Martha had seven children who ranged in age from 18 to 2. They were Nancy Holland, b.c. 1785, Henry Walker Holland, b.c. 1788, William Holland, b.c. 1794, Elizabeth Holland, b.c. 1796, Richard “Dick” Holland, Jr., b.c. 1797, John “Jack” Holland, b.c. 1798 and Martha “Patsy” Holland, b.c. 1801.[3]

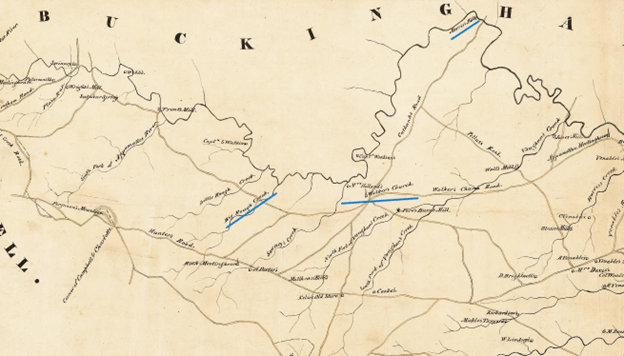

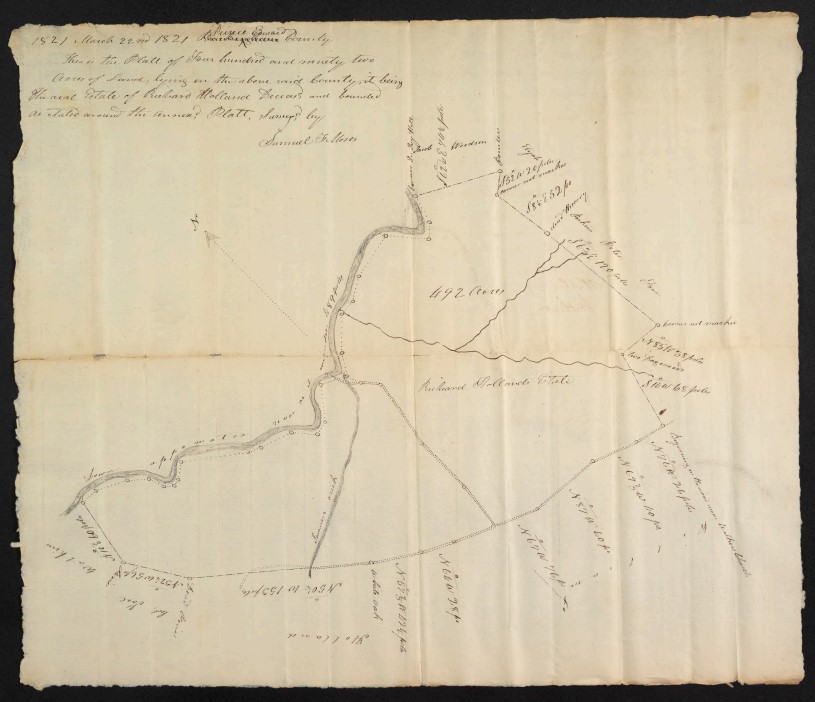

Portion of an 1820 Prince Edward County map.[4] Mrs. Holland’s and Walker’s Church at center right underlined in blue. Mrs. Holland was Martha (Jones) Walker Holland, widow of Dick Holland. This land was part of a 2,000 acre tract in Amelia County on both sides of Vaughan’s Creek patented in 1739 by Charles Hudson.[5] In his 1745 will, he directed his executors to sell 1,000 acres and lent 500 acres of this tract for life to his daughter Sarah (Hudson) Holland and another 500 to his daughter Ann (Hudson) Lewis.[6] At Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s death about 1795, her 500 acres passed to her sons Dick and Christopher Holland as directed in her father’s will. In 1802, Dick Holland’s portion was willed to his sons Henry Walker Holland and William Holland. Dick Holland’s portion was sold for debt. Center left is Rough Creek, the plantation which Dick Holland purchased and willed to his son Dick Holland, Jr. At the upper right is Morris’s Mill owned by John Morris of Buckingham who married Dick Holland’s eldest daughter Nancy. John and Nancy (Holland) Morris are my 4x great grandparents.

In an account given after Martha (Jones) Walker Holland’s death, Dick Holland’s estate it was “greatly in debt” and that “by judicious and prudent management” she acquired “considerable property both real and personal.” She “lived & labored most industriously for her children.”[7] Martha (Jones) Walker Holland outlived her second husband by nearly 20 years making her will 31 October 1820. She died soon after as her will was proven at Prince Edward County Court on 19 February 1821.[8] She had also outlived four of her 10 children including Lucy (Walker) Woods, d.c. 1796, and Dr. James Walker, d.c. 1814 as well as Dick Holland, Jr., d.c. 1819 and daughter Elizabeth (Holland) Stewart, d.c. 1819. Only daughter Elizabeth (Holland) Stewart) left children. Surviving Martha were her sons Henry Walker Holland, William Holland and John Holland, daughters Nancy (Holland) Morris and Martha (Holland) Trent and the underage children of her deceased daughter Elizabeth (Holland) Stewart including Mary S., John D. and James W. Stewart.

Trent vs. Holland – the enslaved are divided among a new generation

A month after Martha’s will was recorded, her son-in-law and youngest child Thomas & Martha “Patsy” (Holland) Trent brought suit in Prince Edward County Chancery Court to have the estates of Dick & Martha (Jones) Walker Holland divided.[9] Luckily, we have a 107 image file spanning seven years to tell us all about it. By way of reminder, Dick Holland’s 1802 will included two clauses that were the basis for this suit:

First he lent his widow for her lifetime three enslaved women named “Eady, Jenny and Dinah and their increase.” He also empowered Martha giving her “the discretion of my beloved wife Martha Holland to give to any of my children or to all of them as she shall think proper at her own discretion.”

Second, Dick Holland directed his executors to “lend unto my Children as they come of age or marry at their discretion out of my estate that I have [cut off, prob. “not”] bequeathed, any part that they shall think proper.” Further he directed that “my Children shall be raised out of my Estate, and at the death of my dearly beloved wife, Martha Holland, all the Estate they may have Lent my Children shall be brot [brought] together and equally divided among all my Children or their Heirs.”

With respect to the first clause, in her own will dated 31 October 1820, Martha left son John Holland “one Negro woman named Dinah and her Child named Henry to him and his heirs forever; also, one yoke of oxen and Cart which my Son Dick gave me and one Black Horse.” She bequeathed “my Daughter Nancy Morriss one Negro woman Jenny and one negro woman named Leene and her two Children Frank and Harriott, to her and her heirs forever.” To her daughter Martha Trent she bequeathed “one negro boy Lewis and one Negro woman named Mary to her and her heirs forever.” To her granddaughter Anne Holland “Daughter of my son Henry one negro girl named Lucy to her & her heirs forever.” To the “Children of my [deceased] daughter Elizabeth Stewart, one negro boy named Spencer (son of Jenny) to them & their heirs forever.” She appointed her son William Holland and son-in-Law John Morris as her executors.[10] While the suit filed by Thomas and Martha (Holland) Trent went to great lengths to praise Martha Holland, they also claimed that she had made various bequests that “would be found under scrutiny that she had disposed of slaves that properly belong to the estate.” She also, “in favor of a grandchild, had disposed of one of the descendants of the slaves over whom she had a power of appointment in a manner not strictly legal.” They also claimed she did not “settle her accounts as executor of her husband.” She also, they alleged that she failed to dispose of by will a small tract of land in Prince Edward County.[11]

With respect to the second clause, Dick Holland’s will directed that at his wife’s death everything loaned to his children from the estate – everything other than what was bequeathed in his will – was to be returned, appraised and distributed evenly among his children. The case file reveals that Martha (Jones) Walker Holland bought out the interests of Dr. James Walker (her son) and Micajah Woods (former son-in-law of deceased daughter) in her first husband’s estate. In 1803, she purchased the enslaved people she held a life interest in by dower. Then about 1812 she bought the 866 acre Walker plantation on Vaughan’s Creek. The bachelor Dr. Walker was well settled in Buckingham County and Micajah Woods was remarried with a family in Albemarle County. The Henry Walker plantation was adjacent to Dick Holland’s 766 plantation. Martha then convinced son William Holland to forgo his half of the 766 acre tract left to him by his father and to take a 550 acre portion of the Walker plantation instead. There are several pages devoted to whether the land given to William was loaned rather than bequeathed by will and to Henry and William getting a greater share than by Dick Holland’s will.

In a deposition, Frances “Fanny” (Anderson) Holland (widow of Dick Holland’s brother Christopher Hudson Holland) said that Martha Holland told her that she intended to give her son John Holland the tract of land she then lived on [Henry Walker dower land] and intended to give her son Dick [since dead] one “negro boy named Peter” to make up the deficiency in the value of his land with the other sons. Fanny Holland also testified that Martha Holland said that she “intended to give to her daughters the negroes that her late husband Dick Holland left to her disposal by his will, to make their proportion in negroes equal to her sons in land.”

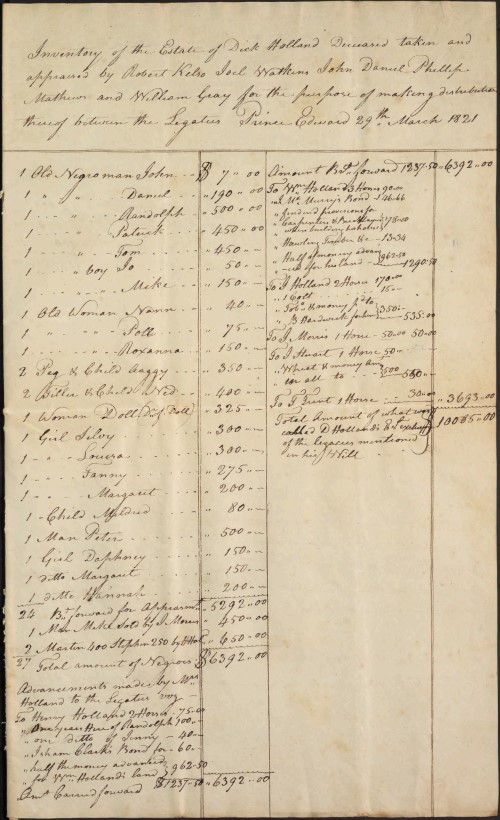

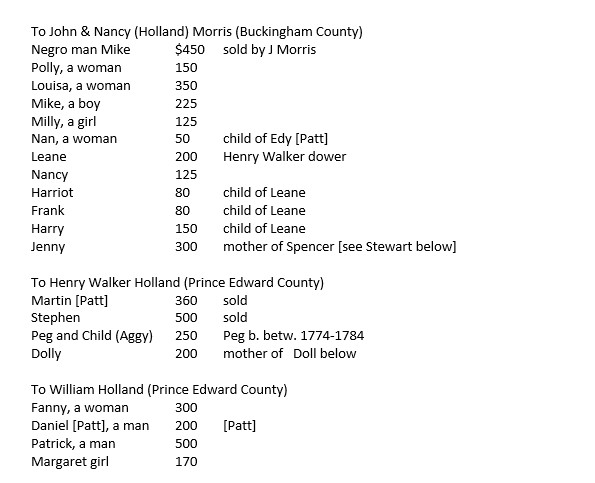

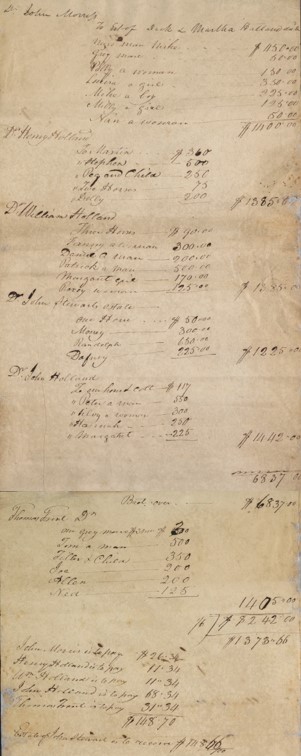

The file includes the estate inventories of both Dick and Martha (Jones) Walker, which consists principally of enslaved men, women and children [the numbers below are the appraised values of the enslaved people, which helps in estimating their ages]:

1821 Dick Holland Inventory:

Old man John 7, Old man Daniel 190, man Randolph 500, man Patrick 450, man Tom 450, boy Jo 50, boy Mike 150, Old Woman Nann 40, old woman Poll 75, woman Roxanna 150, Peg & child Aggy 350, Tiller & child Ned 400, Doll (daughter of Doll) 325, girl Silvey 300, girl Louisa 300, girl Fanny 275, girl Margaret 200, child Mildred 80, man Peter 500, girl Daphney 150, girl Margaret 150, girl Hannah 200, man Mike sold by J. Morris 450, Martin 400 sold by H. Holland, Stephen 250 sold by H. Holland

1821 Martha Holland Inventory:

woman Leane 200, girl Mary 400, girl Cate 300, girl Lucy 200, girl Nancy 125, girl Harriott 80, girl Harry 150, girl Frank 300, man Allen 300, child Spencer 50, Dinah & child Henry 500, girl Martha 300, girl Jenny 300, girl Nancy 200, boy Friday 150, boy Lewis 275, boy John 275 & 1 Old negro Woman Lucy supposed to be 100, worse than nothing. Leane Nancy, Harriot, Frank, Harry, Mary & Cate. Which said Leane & Mary were purchased byMartha Holland from Micajah Woods & James Walker. With Martha Trent Harriott, Frank, Harry, Mary & Cate are children of Leane. Harriott, Frank, Harry, Mary & Cate and children of Leane, said Nancy & Harry were given by Martha in her lifetime to John & Nancy Morris and Cate given to Thomas Trent & Martha.

The estates are divided . . . and then redivided

The commissioners appointed to divide the estates of Dick and Martha delivered their report “as near law and equity as the nature of the case would admit.” They offered a considerable explanation of their decision, ultimately concluding that that the widow had overstepped her authority because she had used the profits of the estate of Dick Holland – to which each legatee had an equal share – to favor Henry and William with more land than their father left them in his will. They then concluded that she attempted to make up the difference with the way she distributed the enslaved in her will. In Martha’s will she also gave an enslaved girl named Lucy to her granddaughter Ann Holland, daughter of Henry Walker Holland. The commissioners noted: “We considered that Mrs. Holland had not the power of conveying a complete title to the said negro, but as we understood she gave it on account of the misfortune of Ann Holland (to wit: that of losing one of her eyes) and all the legatees except the children [of deceased daughter Elizabeth (Holland) Stewart] were present and approving of the gift, We were of the same opinion.”

The Commissioners stated, “We consider the most equitable plan for division was to be governed by the will of Dick Holland and bring the whole estate into hotchpot (specified legacies excepted) having no regard to former gifts or bequests of Mrs. Holland to any of the children owing to a “deficiency in title to several of the negroes.” Then they concluded “Taking all circumstances into consideration and for the better preventing of further controversies we are unanimous of opinion that the division made is just and impartial by causing all the legatees to account for what they received from their mother since the death of their father.” They went on to say “The two sons who received an extra quantity of land to account for the money paid for it and the others to account for the negroes at what they were worth at the time they were given to them. The decree directed us to settle the accounts of the executors which cannot be done at this time for the following reasons Mrs. Holland who was the executors of Dick Holland and as before notice had the whole management of the estate which she conducted admirably well altho’ she never put pen to paper therefore had no account either to settle or keep to herself and her executives are just commencing their labors, as their accounts are not ripe for settlement.”

Fair is in the eye of the beholder

The sons-in-law John Morris (Nancy) and Thomas Trent (Martha) contested the decision saying that not all of the legatees (Henry & William ) had been required to account for their land given to them by Martha out of the profits of the estate, both the wills of Dick and Martha should be valid. The decision was ultimately reversed. The court found both wills operative, that sons Henry and William owed money to the estate for the land outside of the will, and that there should be a redistribution of the enslaved to make the heirs equal. This favored the daughters over the prior decision and in 1822 the enslaved were redivided as follows:

Jack Holland and Dinah – off to Missouri

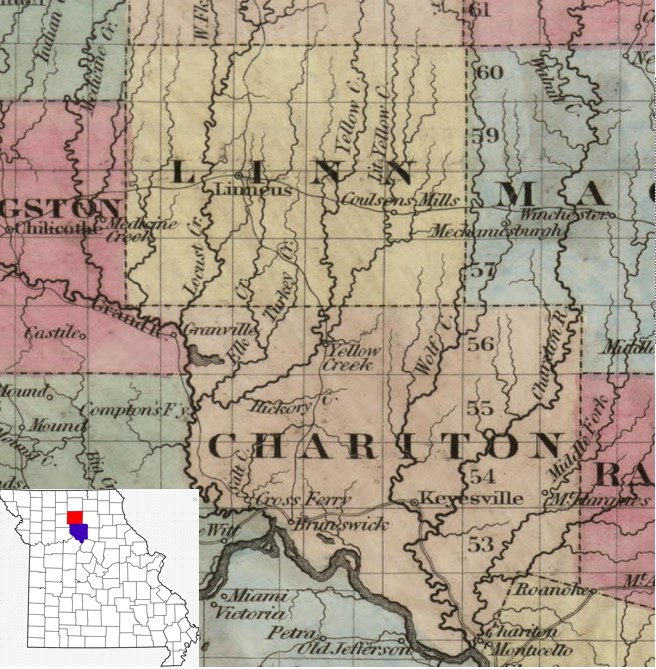

The three surviving Holland brothers all left Virginia during the 1830s for Chariton County, Missouri, which is in the northern part of the state. John “Jack” Holland first visited Missouri in 1832 and settled there with his family in 1834. His brothers and their families soon followed. Eldest brother Henry Walker Holland died in 1840 and his wife in 1841.[12] William Holland’s first wife, Elizabeth ———- died sometime during the 1840s. He married Sarah Pulliam in 1849 and then he died in 1850.[13]

Inset of 1851 Map of Missouri.[14] Note Linneus and Locust Creek in western part of Linn County (John Holland) and Keytesville in eastern Chariton County (Henry Walker Holland and William Holland)

Jack Holland settled in the northern portion of Chariton County that became Linn County in 1837. Well, it turns out that Jack Holland was the founder of Linneus, Missouri, which became the county seat of Linn County. In 1839, Jack and his wife Elizabeth (Woolridge) Holland donated fifty acres to the county for a permanent county seat at Linneus.[15] You may recall that among the enslaved people distributed from Dick Holland’s estate to Jack Holland in 1828 and Dinah and her child Henry.

A History of Linn County, Missouri published in 1882[16] offers an extensive portrayal of Jack Holland and the enslaved Dinah. What follows in italics is directly from this 1882 history:

The first settler on the town site of the town of Linneus was Colonel John Holland, who came from Virginia to Linn county in the early spring of the year 1834:, and located his claim on the section whereon the capital of the county now stands. Colonel Holland’s cabin was of hewed logs, and comprised two rooms. In this double cabin court was afterwards held, school taught, and a great deal of important public business transacted. The cabin stood near the center of the public square. Heavy timber — or at least a heavy growth of timber — stood all about for some years, and upon its first occupancy, its inmates were often lulled to their slumbers by the howling of wolves and the hooting of owls. The Colonel once related that at the first breakfast ever eaten in this cabin the principal dish was a brace of stewed squirrels which he shot from the trees that surrounded his domicile while standing on his doorstep.

Soon after he had built his cabin, Colonel Holland set about digging a well. His negro man Peter was at work on the job, and had dug down twenty feet when he came upon a large stone. He left the well to get a proper implement to raise this stone, which he had already loosened. When he again descended, he was prostrated by the fire-damps, which it was believed had come into the well with the loosening of the stone. Colonel Holland called his good wife, Elizabeth, and bade her assist him in rescuing poor Peter, who, like truth, was at the bottom of the well and crushed to the earth. Mrs. Holland, though a slight woman and commonly not of much strength, lowered her husband to the bottom, and he at once fastened a rope to the gasping negro, and then ordered his wife to haul him (the Colonel) up. She began to do so and just then the Colonel himself was overcome by the damps and fell senseless into the bucket. Mrs. Holland under the excitement succeeded in drawing her husband out in safety and then screamed for help. A settler who chanced to be near, heard her and came to her assistance. By his help not only did Mrs. Holland get Peter out of his predicament, but she restored her husband to consciousness, thus saving two human lives, and adding another incident to the long list of heroic actions performed by the pioneer women of Missouri.

The first occupant of Holland’s cabin was his negro woman, Dinah, who came up with her master to cook for the men who built the cabin, and care for the house until the family should come. Colonel Holland brought with him some thirty head of sheep, and these were the especial charge of Dinah. The dusky shepherdess led her flock each day to the woods, to let them “browse” upon the buds of the hazel and elm, and great was her concern lest the ravenous wolves with which the forest was infested, should raid upon the innocent sheep and devour them. At night she penned them in one room of Holland’s cabin, while she lay down to sleep in the other. A huge mastiff, cross and vigilant kept watch and ward outside. In the daytime this dog was kept chained. “Aunt” Dinah remained in charge of her master’s property for several weeks, for Colonel Holland was delayed in his return by reason of the swollen streams. All the while she was alone. Occasionally William or Jesse Bowyer would pass by the cabin and see that all was right. She had plenty of provisions, but would not accept any venison or other fresh meat lest the smell should attract the wolves, and they should break through every obstacle and slay her.

“Aunt” Dinah, the first female inhabitant of Linneus, still lives in the place, aged eighty-eight. Her daughter, aged about sixty, takes care of her. Relating her early experience to the writer, Dinah said: ” I members de time vary well, massa, when Massa Jack Hollan’ fotch me wid ‘im. Dey was nuffin but woods and woods; an’ in de woods was wolves and wolves. I tuck keer of de sheep for mont’s. De wolves ‘ud jist come right up in sight and howl and yowl, an’ at night when I druv de sheep in de cabin, an’ shot de doah an’ prop’t it tight, and turn’ de dog loose, an’ him an’ de wolves jist had it fum dat till mawnin’. Bimeby [by and by] come along Billy Boyah or Jess’ Boyah, an’ dey say, ‘ Howdy, Dinah, how you git along?’ I say, ‘Monstrous lonesome.’ An’ dey say, ‘ Well, don’t git skeered, ‘an you’ll come along all rite.’ So it went on an’ went on, an’ went on, an’ nobody come, an’ I got so lonesome, tenin’ to dem sheep an’ luffin ’em browse, an’ singin’ to my own self ‘kase I didn’t feel so ‘fraid when I heerd my own voice; an’ never seein’ nobody ‘cept once in a while Billy Boyah, or Jess’ Boyah, or Massa Jedge Clark, an’ dey all de time say, ‘Don’t git skeered, Dinah; Jack Hollan’ come bimeby.’ An’ so one day I heerd a big nise, an’ wagons a rum’lin’, an’ cattle a bawlin’ an’ men a hollerin’, and, sure ’nuff, dere dey was — Massa Jack Hollan’ an’ Missis Hollan’ (my fust Missis Hollan’), an’ all de chillun, an’ de black folks, an’, O, Lawd! I was so happy I hollered right out so you could a heern me a mile.”

Upon Colonel Holland’s death, July, 1855, according to the provisions of his will, Dinah was set free. Ever since she has lived and about Linneus, Peter, the negro who was overcome by the tire-damps in Colonel Holland’s well, was afterwards sent down into Chariton county and hired out. Becoming tired of his condition of servitude, he concluded to free himself, and one night “struck out for the north star,” as the act of running away to the Iowa abolitionists was then expressed, and was never heard of in these parts again.

Well, isn’t that something?

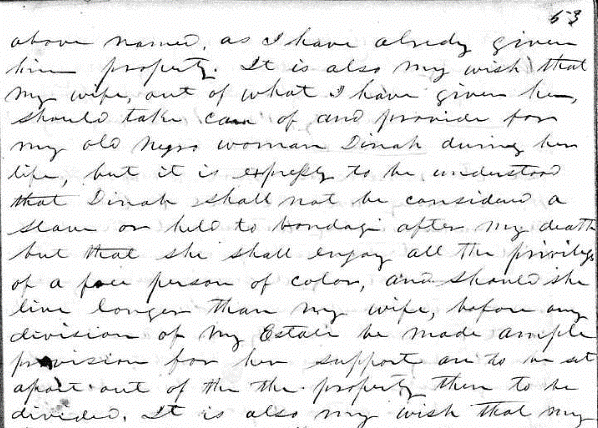

Jack Holland’s Will

Jack Holland did, in fact, die in 1855 and left a will. [17] The 1882 Linn County history states that Jack Holland freed Dinah in his will. His will states, “It is also my wish that my wife, out of hat I have given her, should take care of and provide for my old negro woman Dinah during her life, but it is to be expressly understood that Dinah shall not be considered a slave or held to bondage after my death but that she shall be enjoy all the privileges of a free person of color, and should she live longer than my wife, before any division of my estate be made, ample provision for her support are to be set apart out of the property then to be divided.”

The rest of Jack Holland’s bequests

In addition to directing certain lands sold to pay his debts, bequests of land to his wife and sons, he divided his enslaved people among his wife and children:

To his wife Elizabeth[18] – Solomon, Mary & Ellen

To daughter Mildred – Edith, if she dies, then Ellen when wife dies

To son John Thomas – Henry

To son Joseph Edward (under 16) – Tom

To daughter Ann Virginia – Harry, to remain with his mother until two years old [doesn’t identify mother]

Dinah’s family in freedom

The 1882 Linn County history also said that Dinah was alive to be interviewed well after the Civil War. According to the writer, she lived with her daughter. I searched the 1870 and 1880 United States. Not knowing what surname she took after the Civil War, I searched for Dinah (no last name) in Linn County, Missouri.

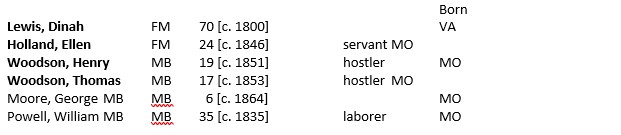

In 1870, I found Dinah Lewis, a mulatto woman, age 70, born in Virginia and unable to read or write, who headed a household in Locust Creek, Linn, Missouri. Included were:

Dinah, Ellen, Henry and Thomas were all mentioned in Jack Holland’s 1855 will.

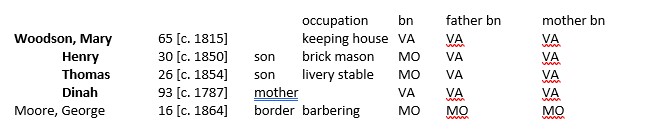

Then in 1880, I found Dinah living with her daughter Mary Woodson and listed as being 93 years old. Her grandsons Henry Woodson and Thomas Woodson were living there as well:[19]

The last record of Dinah is from the local newspaper in Linneus, Missouri in 1886. An article entitled, County Court Proceedings 6 April 1886 includes a section called Allowances, which contains a single line that reads: “Thos. Woodson, coffin for Dinah Holland $4.00”[20] Thomas Woodson was Dinah’s grandson.

Epilogue

If you’ve read my entire Holland series, we have come a long way together. Beginning in 1743 Hanover County, Virginia with the gifting of 12 enslaved men, women and children. Then we went from Henrico County to Louisa County and then to Prince Edward County with a couple of side trips to Rowan County, North Carolina. Then we ventured nearly 1,000 miles to Linn County, Missouri ending up in 1886. That’s 143 years – 122 of them before the end of slavery. We have met four generations of the Hudsons and Hollands – as well as four generations of the families of Patt and Hannah.

Reading about Richard and Sarah’s world slowly crumbling, one can’t help but feel the impact on the people they enslaved. Being mortgaged, hired out annually by your enslaver’s creditors, and perhaps ultimately sold seems an ugly fate. It’s not difficult to imagine the sorrowful scenes of separation. We learned about British and Scottish merchants like Cochran and Donald [who seemed to have altered their firm name constantly] and how risky the relationship with them could be for both the enslaver and the enslaved. The 1774 public auction and the multigenerational plan executed by the Hollands to retain Patt and Hannah and their descendants is as interesting as it is horrifying. While in no way done for the benefit of the enslaved, the scheme did prevent the families of Patt and Hannah to remain largely intact if but for a while. It was a pleasant surprise to find Dinah and her family after the Civil War. Lastly, here are a few last updates on what happened to a few of the people introduced along the way.

The 10 men mortgaged in 1800

Remember the 10 enslaved men mortgaged by Dick Holland that Donald & Cochran had finally won the forced sale of back in 1802? Eight of the 10 men were included in Dick Holland’s 1821 inventory. Perhaps it is a coincidence that of the eight men accounted for therefore not sold in 1802, six were descendants of Patt and/or Hannah. Of the four men not known to be descendants of Patt or Hannah, we know nothing of the fate of Cezar or Jerry, and Micheal, although found in Dick Holland’s 1821 inventory, is listed as “sold by J. Morris.”

Descendants of Patt and Hannah

John [Patt] – 1821 “old John” Dick Holland Estate; 1822 allotted to John Holland

Daniel [Patt] – 1821 he is “old man Daniel” Dick Holland Estate

Lewis [Patt] 1821 to Trent

Randolph [Patt] – 1821 Dick Holland estate, 1822, John & Elizabeth (Holland) Stewart estate

Ned [Hannah] – 1821 allotted to Trent

Tom [Hannah] – 1821/22 allotted to Trent

Not known to be descendants of Patt or Hannah

Patrick – 1821 Dick Holland estate; 1822 went to William Holland

Cezar – no further record

Jerry – no further record

Michael – 1821 Man Mike sold 450 by John Morris

Edy and Jenny

Edy [Patt] and Jenny were among those enslaved women Dick Holland willed to his wife in 1802 for her life and then empowered her to decide how they and their “increase” should be divided among his children. Edy [Patt] appears to have died before the 1821 inventories of Dick and Martha (Jones) Walker Holland were made. Her children Martha, Friday, Nancy, Lewis and John were all willed to Nancy (Holland) Morris by Martha (Jones) Walker Holland in 1820. The Morris’ lived in Buckingham County and owned Cutbanks plantation in Prince Edward County. I was not able to find out anything about the fates of Edy’s children.

Jenny and her son Spencer were part of the 1822 estate distribution with Jenny and Spencer (who was not more than a toddler) separated. Jenny went to John and Nancy Holland) Morris while Spencer went to Thomas and Martha (Holland) Trent. The Trent’s lived in the part of Prince Edward County that became Appomattox County in 1845. Spencer died in March 1862 in Appomattox County about age 40 from pneumonia. His enslaver at the time of his death was William Trent, son of Thomas & Martha (Holland) Trent).[21]

Ann (Holland) Flournoy – a pioneer – twice

Remember Ann Holland the granddaughter of Martha (Jones) Walker Holland we met back in 1820? She’s the one who had the misfortune of losing an eye causing her grandmother to will her an enslaved girl named Lucy – later part of the Trent v. Holland suit. Ann Holland (c.1812-1893) had an interesting life. During the 1830s she moved to Chariton County, Missouri with her parents Henry Walker & Sarah (Morris) Holland and her brothers Richard E. Holland (b.c. 1814-1864) and Nathaniel Morris Holland (b.c. 1816-1846). Her parents died in 1840 and 1841 respectively. On 27 February 1845 she married Augustus Woolridge Flournoy, a native of Chesterfield County, Virginia. Nearly two decades later with her parents and brothers all dead, Augustus, Ann and their three daughters left Missouri for the Idaho Territory, which had just been organized by Congress the prior year and signed into law by President Lincoln. A couple of her nephews also ended up in the Idaho Territory as well. Augustus Flournoy, who had served in the Missouri state senate, served in the Idaho territorial legislature including a term as speaker. He died in 1878. Ann (Holland) Flournoy died on 8 April 1893 at age 81. She and her husband are interred at Pioneer Cemetery in Boise, Idaho.[22] Can you imagine growing up in well settled Prince Edward County, Virginia, moving to the Missouri frontier when she was in her early 20s, marrying and having three daughters, then in her early 50s moving to the Idaho frontier? A 2x pioneer!

Family Trees

[1] In July 1803, William Jones, Sr. of Buckingham County “for and in consideration of the natural love and affection which he bears toward the said Nancy Holland, Henry Holland, William Holland, Dick Holland, Elizabeth Holland, John Holland & Martha Holland, his grandchildren” two enslaved men named Ned & George whom he had previously purchased from their father Dick Holland. This deed was recorded at the Buckingham County Court on 12 September 1803. The Buckingham Courthouse burned in 1869 destroying this deed and most county records. Fortunately, the deed was included in Prince Edward County Chancery Suit file 1825-003 Henry W. Holland vs. John Morris & wife, image 14 of 15. Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia, Digital Collections; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=147-1835-010

[2] On 9 April 1801, Dr. Walker placed an ad in the Virginia Argus newspaper, which ran on 14 April , notifying the public he “will commence inoculation at his hospital in the county of Buckingham” with a vaccine for Cow Pox. The Virginia Argus, 14 April 1801, Richmond, VA, Vol: VIII, Issue: 102, Page: 3; www.genealogybank.com

[3] Will of Richard “Dick” Holland, Prince Edward County, Virginia, Will Book 3 1795-1807, p. 286, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-L9R3-8?i=290&cat=378289; accessed 19 September 2023

[4] Virginia Board of Public Works, Prince Edward County, 1820, Library of Virginia, Archives Research Services Map Collection; http://digitool1.lva.lib.va.us:8881/R?func=collections-result&collection_id=1519 ; accessed 5 September 2023

[5] Land Office Patents No. 18, 1738-1739, p. 44 (Reel 16), Library of Virginia

[6] Will of Charles Hudson. Henrico County Chancery Suit No. 1782-004, Robert & Mary Price, Etc. vs. Sarah Lewis &c By Etc., Oversize Box 1, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[7] Prince Edward County, Virginia Chancery Court Case NO. 1824-002; Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=147-1824-002

[8] Will of Martha (Jones) Walker Holland. Prince Edward County, Virginia, Will Book 5 1815 – 1822, p. 484, Reel 16, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[9] Prince Edward County, Virginia Chancery Court Case No. 1824-002; Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=147-1824-002

[10] Prince Edward County Will Book No. 5 1815-1822, p. 484; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-L954-T?i=495&cat=378289

[11] Prince Edward County, Virginia Chancery Court Case NO. 1824-002; Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=147-1824-002

[12] Craig, P. Steven. Along the Willis River: Descendants of Nathaniel & Nancy (Jeffries) Morris of Buckingham County, Virginia, (Henrico, Virginia: self-published, 2016), p. 40, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[13] U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current, Ancestry.com

[14] Colton, G. W., Atwood, J. M. & Colton, J. H. (1851) Colton’s new map of Missouri: compiled from the U.S. Surveys and other authentic sources. New York: Published by J.H. Colton. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2018588056/.

[15] The History of Linn County, Missouri (Kansas City, MO: Birdsall & Dean, 1882), p. 190

https://archive.org/details/historyoflinncou01kans/page/6/mode/2up

[16] The History of Linn County, Missouri (Kansas City, MO: Birdsall & Dean, 1882), p. 402

https://archive.org/details/historyoflinncou01kans/page/6/mode/2up

[17] Ancestry.com. Missouri, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1766-1988 [database on-line]. Lehi, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2015. Original data: Missouri, County, District and Probate Courts.

[18] This is his second wife Elizabeth Relph whom he married in 1844. His first wife Elizabeth Woolridge died in 1841.

[19]1880 United States Federal Census; Census Place: Linneus, Linn, Missouri; Roll: 700; Page: 502A; Enumeration District: 186; Ancestry.com

[20] The Bulletin, Linneus, Missouri, Thursday, April 15, 1886, p .1; newpapers.com

[21] “Virginia Deaths and Burials, 1853-1912”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:HJTM-BQT2 : 29 January 2020), Spencer, 1862.

[22] Craig, P. Steven. Along the Willis River: Descendants of Nathaniel & Nancy (Jeffries) Morris of Buckingham County, Virginia, (Henrico, Virginia: self-published, 2016), p. 83, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

![Part 4 – Dick and Martha (Jones) Walker Holland, their children & Edy [Patt], Jenny and Dinah, some of the people they enslaved Part 4 – Dick and Martha (Jones) Walker Holland, their children & Edy [Patt], Jenny and Dinah, some of the people they enslaved](https://i0.wp.com/asonofvirginia.blog/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/photo1dickhollandexecutors.png?resize=975%2C461&ssl=1)