If you missed Parts 1 & 2, you really should start here:

CONTENT GUIDANCE: When I undertake a study of my Virginia ancestors, I find every source I can about a person or a group of people and find that it usually tells a story. Sometimes one record, such as a will or estate inventory tells a story by itself. Sometimes there is more. The Holland story that spoke to me is one of multigenerational debt, mortgaging enslaved men, women and children and repeated lawsuits by creditors to force their sale to collect the debt. It’s also the story of Patt and Hannah and their many descendants. This blog post explores the enslavement of men, women and children by my Holland ancestors. It contains both language and imagery many will find disturbing. It is made all the more difficult by learning about a topic through getting to know individuals and families rather than in the abstract background topic. Please read with care.

Reminder: Throughout this series I am using [Patt] and [Hannah] behind names of their known descendants.

Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s death brings a new round of debt lawsuits

Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s c. 1795 death removed the remaining impediment for Cochran & Donald. Soon after the 1774 auction the Revolutionary War disrupted debt collection by British Merchants from 1776-1783. While Dick Holland had purchased the enslaved, he apparently did not purchase Sarah’s “life use” legal interest in the enslaved Patt and Hannah as well as their many descendants. With her death, Cochran & Donald soon revived their claim against Dick Holland.

Her death also resulted in a suit heard by the Virginia High Court of Chancery. This court, created in 1777, met in Richmond and heard equity for the entire state of Virginia until 1802 when it was replaced with regional Superior Courts of Chancery. The High Court of Chancery records were lost in the April 1865 fire that was set by retreating Confederates. Not only did the fire end up burning down Richmond’s commercial district, but many government buildings were also destroyed. Lost were the records they held, which included not only the High Court’s files, but many county records that were sent to Richmond for safekeeping during the war.

Nonetheless, sometimes the genealogy gods smile upon us and we find out about such a case through other records. Sometime between Sarah’s c. 1795 death and 1800, Christopher Holland sued Dick Holland alleging that he was entitled to some of the enslaved people that had belonged to their mother. With their sister Mary (Holland) Hughes having died in 1794, her estate was represented by her eldest son and administrator, Hudson Hughes. More on that later.

Cochran and Donald come after Dick Holland

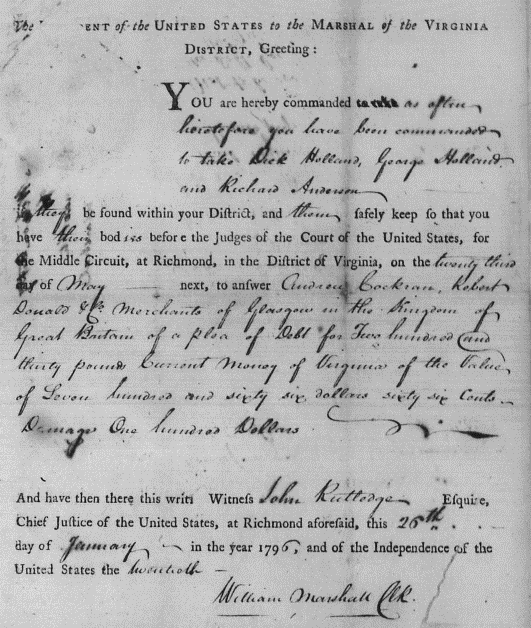

In 1796, Cochran, Donald and Co. brough three suits against Dick Holland and his security Richard Anderson.[1] A 26 January 1796 court order from William Marshall Clerk of Court to the Sheriff said, “You are hereby commanded as often heretofore you have been commanded to take Dick Holland, George Holland and Richard Anderson, if they be found within your district, and them safely keep so that you have their bodies before the judges of the Court of the United States for the Middle Circuit at Richmond on the 23rd day of May to answer Andrew Cochran, Robert Donald & Co of Glasgow in the Kingdom of Great Britain, of a please of Debt for £230 current money of Virginia of the value of $766.66.”

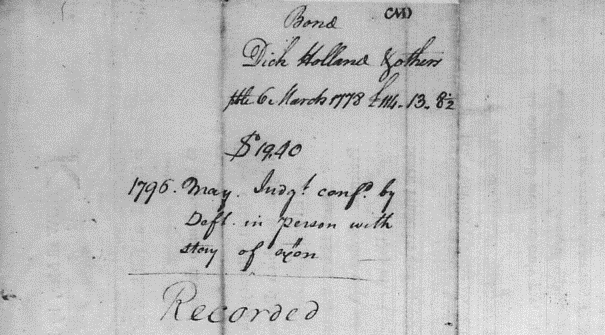

There is little else in the file, but on the reverse of the above order there are notes written by Clerk William Marshall and Deputy James Wilson who served the warrant. Marshall wrote “Debt due on Bond Bailed Required, Not to be executed on the Deft Geo Holland.” Deputy Wilson added his own note: “Executed on Dick Holland & escaped 14 May 1796 exceeding 100miles.” Finally, there is a notation dated May 1796 – “Judgt confessed by Deft in person with story of exon.”

Recalling earlier accusations of the same behavior, did Dick Holland, perhaps knowing of what was coming, go to North Carolina with some of the enslaved people he held to thwart Cochran, Donald & Co.? Did he leave the enslaved with his brother-in-law and sister and come back and go to court to argue he should be exonerated?

The 1796 suits must have not been successful because in 1800, two other cases were brought in the U.S. Circuit Court by Donald & Cochran against Dick Holland and his securities.[2] This time he lost both suits acknowledging debts of $1,622.94 and $1,950.90 with additional interest and costs. For security, Dick Holland did just what his parents had done many years before in mortgaging enslaved people to secure the debt. For the first suit, he mortgaged five enslaved men named John [Patt], Ned [Hannah],Cezar, Patrick and Tom [Hannah]. They were allowed to stay with Holland until their day of sale, which was to take place at Robert Kelso’s store on 13 November 1800. For the second suit, Dick Holland was notified that he was to be at Court on 22 November 1800 to either pay the debt or produce another five enslaved men he had mortgaged named: Jerry [Patt], Daniel [Patt], Randolph [Patt], Michael and Lewis [Patt] for sale at Kelso’s store. The Court ruled for plaintiffs and also awarded their legal costs of $811.47. Dick Holland now owed Cochran and Donald nearly $4,400 plus interest which was still accruing.

Hughes v. Holland and the Holland v. Holland Chancery case

In both 1801 and 1802, on behalf of his mother’s estate Hudson Hughes separately sued Dick Holland and Christopher Holland. In 1803 and in 1804, Hughes brought suits against Christopher Holland. All of these suits were for the Hollands failure to adhere to the High Court of Chancery’s order to turn over the enslaved people that had been allotted to Hughes in the Holland v. Holland case.

On 3 September 1801, Hudson Hughes sued Christopher Holland and Dick Holland. John Taggart came to court and “undertook for the defendant” promising that if Christopher Holland lost this case, he would deliver the enslaved boy Aaron [Hannah] or the value thereof and pay damages and costs. Then Christopher Holland did the same for Dick Holland with respect to Biner (Binah) [Hannah] and Jacob [Hannah].[3] These were enslaved people that had been allotted to Hughes, but not turned over as decreed by the court.

In 1802 Hudson Hughes again brought suits against both Dick Holand and Christopher Holland. He asserted again that Christopher Holland was holding an enslaved boy named Aaron [Hannah] valued at $150 that Holland had failed to turn over. Introduced as evidence were letters written by Hudson Hughes to Christopher Holland written in January and received in March 1800 as well as a response letter from Holland to Hughes written 5 April 1800.

While the letters themselves don’t exist, they are recorded, in part, in the court minute books. In his reply, Holland wrote that Hughes had inquired what “fell to you all” meaning their part of Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s estate. Holland advised him that “the valuables lot was drawn for you all” and that “your parts of the negroes are yet in my possession.” Hughes had written “You likewise wanted to know what was done about your sister’s affairs.”

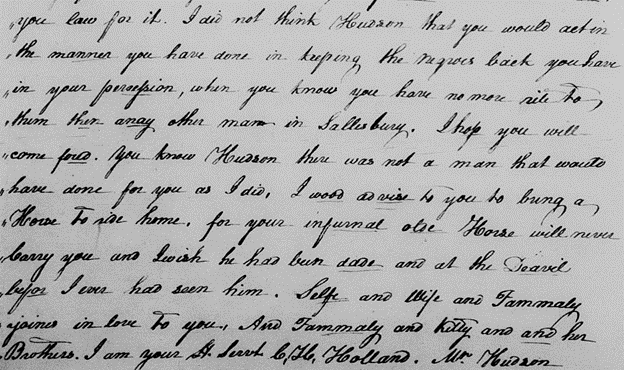

Christopher Holland wrote to Hughes that he had sent Hughes several letters requesting his part of Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s estate [enslaved people] being held by Hughes. He noted that Hughes had advised him that his attorney told him to keep them. Holland wrote to Hughes that he hoped his lawyer would not “direct you to keep my horse.” Holland said he would sue him and that “I did not think that you Hudson would act in the manner you have done in keeping the negroes back you have in your possession, when you know you have no more right to them than any other man in Salisbury (Rowan County, NC). I hope you will come forward. You know Hudson there was not a man that would have done for you as I did. I would advise you to bring a horse to ride home for your infernal old horse will never carry you and I wish he had been dead and at the Devil before I ever laid eyes on him. Self and wife and family joins in love to you and family and Kitty and her brothers [Hudson Hughes siblings].”

Quite the affectionate close after all the berating.

Other evidence introduced in that case was that Aaron [Hannah] had been allotted to Mary (Holland) Hughes by the High Court of Chancery. The jury found for Hughes in this case and directed Christopher Holland to turn over the enslaved man or pay Hughes $150 plus his damages.

In the second case, this one against Dick Holland, Hudson Hughes said that Holland was still holding Binah [Hannah] and Jacob [Hannah] valued at $120. Introduced as evidence by Hughes was a letter to him from Dick Holland: “Dear Sir, This will inform you there is to be a division in the black breed of negros” [this is what Hannah and her descendants were called in 1774] who were “to be divided into three parts”, one to “Kitt” meaning Christopher Holland, one to Dick Holland, and one to the children of Mary (Holland) Hughes, deceased. In another letter Holland wrote that “their [sic] has been a division in the Negros, Aaron [Hannah], Solomon [Hannah], Biner [Hannah] and two of Biner’s children [Hannah] fell to your parts which is now in my possession. They were valued at $945. The best of attorneys in Richmond says you ought to have Jim [Hannah], Tom [Hannah], & Charles [Hannah] valued at cash price as they are children of Hannah’s and from your letter to Kitt you say you can’t give them up without a suit. Kitt says he is willing to have them valued in your state. I think you had better come in for the negros [yet] are doing but little. This is the fourth letter I have rote you.” The other evidence introduced showed that Binah [Hannah] and Jacob [Hannah] were allotted by the High Court of Chancery to Mary (Holland) Hughes and that they were detained by Dick Holland and valued at £60 and £40 respectively. The jury found for Hughes and awarded him the enslaved man and woman “if they could be had” or their value plus £10 in damages.[4]

In 1803, Hudson Hughes brought another suit against Christopher Holland. He had not produced the enslaved Aaron [Hannah] and now defaulted on the bond he had issued Hughes a security for £94.13.6 plus interest and costs. The court ordered Holland to turn over the following property to wit: To black mares, one bay horse and one bay mare to satisfy the debt.[5] In 1804, Hughes sued Christopher Holland again for failing to produce Aaron [Hannah] or pay his value. The court ordered the sheriff to take property to wit: “a negro man named Hall [Hannah] and a negro woman named Sall [Hannah]” for sale at public auction. Holland forfeited the bond[6]

Hudson Hughes stated that the enslaved in his mother’s possession at her 1794 death included Tom [Hannah’s son], Charles [Hannah’s son], & Jim [Hannah’s son], Sawney and Doll. All came from Sarah (Hudson) Holland. Hughes said that Tom, Charles & Jim had been with the Hughes family for 15-20 years before his parents’ deaths and that Doll and Sawney were “brought into this state by Mary Hughes a few years before Joseph Hughes death [d. 1793] as a gift from Sarah Holland grandmother of this defendant.” He noted that neither Doll nor Sawney were counted in Mary (Holland) Hughes’ estate as they had been allotted to Dick Holland by the Virginia High Court of Chancery and that Doll has been delivered to him while Sawney was purchased by Hudson Hughes from Dick Holland. The same chancery suit decreed that Tom, Jim and Charles – “said negroes were to be equally divided between the heirs of the said Sarah Holland viz: Dick, Christopher H. Holland & Mary Hughes.” The file also notes that Mary (Holland) Hughes heirs’ allotment of enslaved people included Solomon [Hannah], Binn [Hannah], Agg [Hannah], Jacob [Hannah], Susanna and Aron [Hannah]. Hughes reported that Solomon had been sold contrary to Hudson Hughes consent by the sheriff of Rowan County and was hen in the possession of the sheriff.

On 19 March 1804, Christopher Holland was deposed in another Prince Edward Chancery Court case seemingly unrelated to the Holland v. Holland case. His testimony in that case, however, does perhaps tell us why he sued his brother. Christopher Holland recalled that he “was on his way to the District Court of Prince Edward and fell in company with Anthony Winston” who asked him “how him and his brother Dick Holland came on at law.” Christopher Holland testified that he told him it was “bad enough that Dick Holland had got all that [enslaved people]” and observed that “Dick Holland was not as generous [with him] as Winston was to Peter Fore.” This involved Winston having lent the labor of two enslaved people to Fore until his children came of age for Fore’s trouble raising the enslaved children until Winston’s children came of age.[7]

While nothing is in the records reveal which enslaved people were allotted to Christopher Holland, contemporary records reveal some of them. On 20 February 1804 Christopher H. Holland mortgaged to John Cheadle “three negroes named Sawney, Buck & Lettie Patt.”[8] In 1805 , John Cheadle released unto Christopher H Holland “all right which I have or ever had to a Negro woman named Winny it being the same Negro purchased by me on 28 November last at a sale made by the sheriff by virtue of three Executions in favor of Venable & Lillye, Robert Venable & John Epperson against Christopher H Holland.” He received from Christopher H Holland $32 “it being the same paid by me for the said negro Winny.”[9] In 1807, Christopher H Holland mortgaged two enslaved people named Hall [Hannah] and Fanny to D. Carlos Green to secure debts.[10] Finally, in 1815 Christopher H Holland sold to Fyatt [Fayette] Holland one enslaved man named Soney [Sawney] for $300.[11]

The Final Donald & Cochran Case

Having lost in Circuit Court owing some $4,400 plus interest and facing the forced sale of the 10 enslaved men he had mortgaged, Dick Holland turned to the Chancery Court. The Court was comprised of the same group of judges as sat on the Circuit Court that had just found against him. On 30 November 1800, he filed a bill for an injunction to prevent the sale of the 10 mortgaged enslaved men.

Dick Holland argued that he had been “deprived of the greatest proportion of his purchase” of the enslaved people he purchased in 1774. No doubt a reference to his brother and his sister’s heirs winning some portion of the enslaved held by Dick Holland. He also noted that under the decree of the county court of Louisa [1774] the proceeds of the auction went to Donald Cochran & Co. Holland. He added that James Strange, their attorney in fact, obtained a judgment against him and will not allow any remedy at common law. Holland argued that Donald Cochran & Company “dwell out of the jurisdiction of the United States.” Finally, he argued for time to depose witnesses and produce other evidence. He also claimed to have paid off one of the bonds to Donald & Cochran, but that their attorney and agent would not work out a compromise, so he was turning to the equity court. The court granted the request for injunction.[12]

James Strange Spills on the 1774 Public Auction

James Strange, the attorney-in-fact and agent for Donald & Cochran, provided an answer to the Court in response to Holland’s bill. He recounted the Louisa County Court’s 1774 order which decreed that the slaves were to be sold to satisfy a debt of £343.3.5 with interest from 9 June 1773 and the surplus, if any, would go to pay Pleasants £74.13.11 ½. He also wrote “That as will further appear by the said proceedings that the said slaves were secreted or removed out of the state.” Stange also stated Dick Holland had “conspired with his father and mother relative to the said slaves by which he was to have the legal title to all or some part of them.” He also said that Dick Holland “made terms with the agent of Donald Cochran & Co for their said debt and accordingly gave bond for the sums specified in the Bill.”

Strange alleged that “the sale was for ready money and thinks it must have been so conducted by the complainant [Dick Holland] who had acquired the title both of the mortgager and the mortgagee as that they should not produce more that the debt otherwise it is impossible to account for the circumstance of thirty negros selling for so small a sum.”Strange also said that was “informed that the said Richard Holland had only a life estate in one of the mortgaged slaves named Hannah and her Increase if she then had any.” He added that Dick Holland “being a member of the family was much more likely than the mortgagees to know how the title stood that he took the mortgage debt on himself before any sale and that from the number of slaves that were clear of all Incumbrance it is apparent that the debt was perfectly secure by means of the mortgaged property on which there was no Incumbrance.”

Finally, Strange offered “that as will appear by the said proceedings, the said Donald Cochran & Co., were in no sort bound to warrant the Title to any part of the said slaves that as will appear by the said proceedings the slaves which the complainant acquired by taking the Debt on himself and to the Title of which there is no objection were worth greatly more than the mortgage debt.” [13]

Strange alleges that Dick Holland took title to some or all of the enslaved before the auction from his parents. Then he was the high bidder for them at the auction and financed the purchase with bonds totaling £468 (£125 & £343) split into three annual payments the first due the following year. Somehow the Hollands had managed after 21 years of being chased for debt by Cochran & Donald, to put off the payment again. Cochran & Donald apparently got no cash payment, agreed to let Dick Holland take on his parents debts, kept the enslaved and the clock began ticking again.

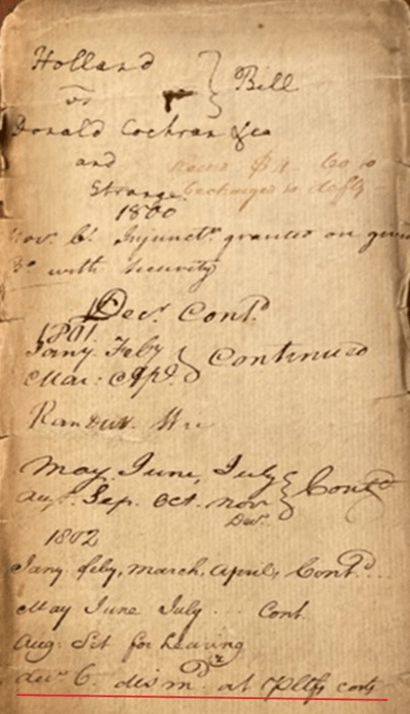

While there is no court decree included in the file, the case schedule is included. Dick Holland filed his bill [complaint] on November 30, 1800. The case was continued in December 1800 and again multiple times during both 1801 and 1802. It was finally set for a hearing in August 1802. The last entry is dated 6 December 1802: “dismd at pltfs costs.” Dick Holland lost the case.

Dick Holland Dies

On 19 April 1802, months before the end of the Cochran & Donald case, Dick Holland wrote his last will and testament. He was dead by 18 April 1803 when his will was proven at the Prince Edward County Court. [14]

Dick Holland was no more than 52 when he died. He spent his childhood watching his parents constantly chased for debts and witnessed the impact of it on both his family and especially on the people they enslaved. As a young, single man, he took on significant debt on behalf of his parents and then spent his entire adult life repeating the pattern. The descendants of Patt and Hannah would sit center stage.

In his will Dick Holland left each of his two eldest sons Henry and William “when he comes of age” half of Dick Holland’s land on Vaughans Creek. To son Dick Holland, Jr. he left a tract called “McFiley” on Rough Creek [present day Appomattox County].[15] With no more land to give, Dick Holland left his youngest son John “one Thousand Dollars in Lew [sic] of Land.” He added a memorandum saying if that was not enough to be equal in value to his “to any one of my other sons that the deficiency shall be made up to [him] when he comes of age.” To his daughters Nancy, Elizabeth and Martha he left each of them “when she comes of age or marryeth two Negro girls one of them to be about twelve or fifteen years old and the other about seven or eight years old.” He left his “beloved brother Christoper [sic] H. Holland all my right to that part of the Land that Robert Venable laid oft [surveyed] it being the Land that he now lives on.”

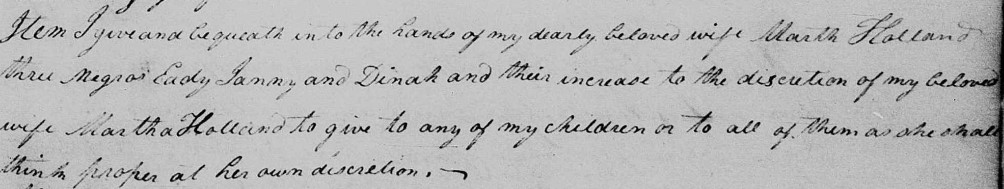

To his wife Martha Holland he left “three negros Eady [Patt], Jenny and Dinah and their increase to the discretion of my beloved wife Martha Holland to give to any of my children or to all of them as she shall think proper at her own discretion.”

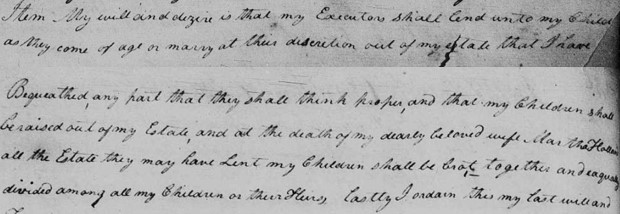

And that “My will and dezire [sic] is that my Executors shall lend unto my Children as they come of age or marry at their discretion out of my estate that I have [cut off, prob. “not”] Bequeathed, any part that they shall think proper, and that my Children shall be raised out of my Estate, and at the death of my dearly beloved wife, Martha Holland, all the Estate they may have Lent my Children shall be brot [brought] together and equally divided among all my Children or their Heirs.”

The last two clauses would prove to be especially important down the road. First, Dick Holland lent his wife three enslaved women named Edy [Patt], Jenny and Dinah and their increase. Then he left it to Martha’s discretion as to how they should be distributed “to any of my children or to all of them as she shall think proper.” Second, as each child came of age or married, Martha, as her husband’s executor, would provide their legacies and beyond that anything else she agreed to advance was a loan from his estate. Then when his wife died, everything “loaned” would be valued and distributed equally. What could go wrong?

Edy [Patt], Jenny and Dinah

As to the origins of Jenny and Dinah, who enter the record with Dick Holland’s 1802 will, we know nothing. Of Edy, however, we know she was no more than five years old in 1774 when she and 13 of her relatives were among the 29 enslaved purchased at public auction by Dick Holland [see Part 2]. Edy’s family was headed by Patt who was styled “ancestress of the rest” in 1774. That was 31 years after Patt was listed among the 12 enslaved people held by Charles Hudson of Hanover County given to his daughter Sarah (Hudson ) Holland as a wedding gift in 1743 [see Part 1]. Sixty years later Charles Hudson and Patt are dead and Charles Hudson’s grandson was making a gift of Patt’s granddaughter. One family, over three generations, had enslaved three generations of another family, for more than 60 years.

Next time:

The Widow Martha (Jones) Walker Holland takes charge of Dick Holland’s indebted estate, we learn what became of the 10 men Dick Holland mortgaged as well as what happened to Edy [Patt], Jenny and Dinah and their descendants.

[1] Donald & Cochran & Co. v. Holland (ended 1796). U.S. Circuit Court, 5th circuit, cases ended 1791-96, restored, Miscellaneous Reel 666-667 B-F, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[2] Cochran & Donald v. Holland & Fore (1800-02). U.S. Circuit Court Records, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, unrestored files, 1800 A-D, Box 50, Barcode: 7420957, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[3] Prince Edward County, Virginia, District Court Order Book 1799-1805, p. 122, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-998R-R?i=719&cat=372336; accessed 1 September 2023

[4] Hughes v. Dick Holland and Hughes vs. Christopher H Holland, Prince Edward County, Virginia, Records at Large District Court 1792-1802, p. 611-617;

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-99DW-S?i=310&cat=372336; accessed 31 August 2023

[5] Prince Edward County, Virginia, Records at Large District Court 1802-1804

Hughes v. C. H. Holland p. 309; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-99D7-8?i=479&cat=372336; accessed 31 August 2023

[6] Prince Edward County, Virginia, Records at Large District Court 1802-18041802-1804

p. 393 Hughes v. C. H. Holland; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-99DQ-K?i=521&cat=372336

[7] Prince Edward County Chancery Court Case No. 1805-013, Peter Fore v. Peter Kelso, Gdn. Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia Digital Collections, https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=147-1805-013

[8] Prince Edward County, Virginia Deed Book No. 13 1803-1806, p. 174; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-JWNQ?i=351&cat=362164 ; accessed 29 May 2023

[9] Prince Edward County, Virginia Deed Book No. 13 1803-1806, p. 439; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-JWZR?i=529&cat=362164; accessed 29 May 2023

[10] Prince Edward County Deed Book No. 14 1806-1812, p. 71; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-Z9Z5-N?i=47&cat=362164; accessed 29 May 2023

[11] Prince Edward County Deed Book No. 15 1812-1816, p. 364; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSYD-Z9CK-2?i=577&cat=362164; accessed 29 May 2023

[12] Bill of Dick Holland sworn in open court 26 November 1800, Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[13] Answer of James Strange, attorney in fact for Donald & Cochran &Co.. 4 December 1800, Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[14] Will of Richard “Dick” Holland, Prince Edward County, Virginia, Will Book 3 1795-1807, p. 286, https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9PX-L9R3-8?i=290&cat=378289; accessed 19 September 2023

[15] Dick Holland bought 300 acres in Prince Edward County from Marris McFieley in 1791. Prince Edward County Deed Book No. 8 1788-1790, p. 324; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKV-NSB8-Y?i=632&cat=362164; accessed 29 May 2023