CONTENT GUIDANCE: When I undertake a study of my Virginia ancestors, I find every source I can about a person or a group of people and find that it usually tells a story. Sometimes one record, such as a will or estate inventory tells a story by itself. Sometimes there is more. The Holland story that spoke to me is one of multigenerational debt, repeated mortgaging enslaved men, women and children and numerous lawsuits by creditors to force their sale to collect the debt. It’s also the story of Patt and Hannah and their many descendants who were enslaved by the Hollands and bore the brunt of the Holland’s financial woes. This blog post explores the enslavement of men, women and children by my Holland ancestors. It contains both language and imagery many will find disturbing. It is made all the more difficult by learning about a topic through getting to know individuals and families rather than in the abstract background topic. Please read with care.

If you missed Part 1 you can catch up here: https://asonofvirginia.blog/2023/08/15/richard-and-sarah-hudson-holland-of-hanover-henrico-louisa-and-prince-edward-counties/

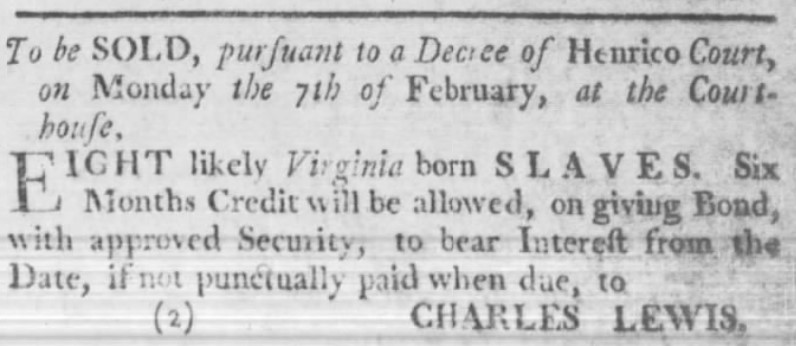

We ended Part 1 in January 1774 when the Louisa County Court ordered that Richard and Sarah Holland’s mortgaged assets be sold by the Sheriff to pay their debts to merchants Andrew Cochran & Co.[1] and Thomas Pleasants. Per the Court’s order, the Hollands owed Cochran & Co. £343.3.8 ½ and Pleasants £74.12.11 ½, both to also get their interest and his costs. The assets included 29 enslaved men, women and children who were to be sold at a public auction.

The Sherriff Carries Out the Court’s Order

It did not take long to execute the Court’s order. In March of 1774, the Louisa Sheriff offered the enslaved men, women and children that had been mortgaged by the Hollands for sale.[2] There were 29 men, women and children waiting to learn their fate. It must have been simply terrifying. I cannot begin to do justice to a description of a public auction for you. Fortunately, we can rely on two men who experienced it firsthand.

Henry Winston was born enslaved in Virginia and described in his 1848 Narrative of Henry Watson, A Fugitive Slave, his own sale at public auction in Richmond when he was a boy of just eight years old:

“I will attempt to give as accurate an account of the language and ceremony of a slave auction as I possibly can. “Gentlemen, here is a likely boy; how much? He is sold for no fault; the owner wants money. His age is forty. Three hundred dollars is all that I am offered for him. Please to examine him; he is warranted sound. Boy, pull off your shirt ⎯ roll up your pants ⎯ for we want to see if you have been whipped.” If they discover any scars they will not buy, saying that the nigger is a bad one. The auctioneer seeing this, cries, “Three hundred dollars, gentlemen, three hundred dollars. Shall I sell him for three hundred dollars? I have just been informed by his master that he is an honest boy and belongs to the same church that he does.” This turns the tide frequently, and the bids go up fast; and he is knocked off for a good sum. After the men and women are sold, the children are put on the stand. I was the first put up. On my appearance, several voices cried, “How old is that little nigger?” On hearing this expression, I again burst into tears and wept so that I have no distinct recollection of his answer. I was at length knocked down to a man whose name was Denton, a slave trader, then purchasing slaves for the Southern market. His first name I have forgotten.”

Another description comes from Josiah Henson who was born enslaved in Maryland and recollected in his 1858 Truth Stranger than Fiction: Father Henson’s Story of His own Life, his family’s sale when he was only five or six years old:

“Common as are slave-auctions in the southern states, and naturally as a slave may look forward to the time when he will be put up on the block, still the full misery of the event ⎯ of the scenes which precede and succeed it ⎯ is never understood till the actual experience comes. The first sad announcement that the sale is to be, the knowledge that all ties of the past are to be sundered, the frantic terror at the idea of being sent “down south,” the almost certainty that one member of a family will be torn from another, the anxious scanning of purchasers’ faces, the agony at parting, often forever, with husband, wife, child ⎯ these must be seen and felt to be fully understood.

Young as I was then, the iron entered into my soul. The remembrance of the breaking up of McPherson’s estate [the property of his first owner] is photographed in its minutest features in my mind. The crowd collected round the stand, the huddling group of negroes, the examination of muscle, teeth, the exhibition of agility, the look of the auctioneer, the agony of my mother ⎯ I can shut my eyes and see them all.

My brothers and sisters were bid off first, and one by one, while my mother, paralyzed by grief, held me by the hand. Her turn came, and she was bought by Isaac Riley of Montgomery County. Then I was offered to the assembled purchasers. My mother, half distracted with the thought of parting forever from all her children, pushed through the crowd while the bidding for me was going on, to the spot where Riley was standing. She fell at his feet and clung to his knees, entreating him in tones that a mother only could command to buy her baby as well as herself, and spare to her one, at least, of her little ones. Will it, can it, be believed that this man, thus appealed to, was capable not merely of turning a deaf ear to her supplication, but of disengaging himself from her with such violent blows and kicks as to reduce her to the necessity of creeping out of his reach and mingling the groan of bodily suffering with the sob of a breaking heart? As she crawled away from the brutal man I heard her sob out, “Oh, Lord Jesus, how long, how long shall I suffer this way!” I must have been then between five and six years old. I seem to see and hear my poor weeping mother now.”[4]

While we have no record of what the Holland’s enslaved people thought about their situation, one can perhaps imagine from these accounts what the horrific scene may have resembled.

Patt and Hannah, daughter of Judy

We are fortunate to have one account of the auction of the Holland’s enslaved people. From a 25 December 1801 deposition of Dabney Miller, taken a quarter of a century after the fact, Miller testified that he had been called upon by either Mr. Turner Southall or Mr. James Buchanan about the year 1775[5] to “buy some Negros in the City of Richmond which were to be sold to satisfy a debt due to Cochran & Donald & Co.” Miller added that “when the first negro was offered for sale, Mrs. Sarah Holland came up and forbid the sale and shewed a will which she said was her father’s” and that Captain Joseph Lewis[6] said that “no right could be made to the said negros.” Mr Goven, agent for Cochran & Donald & Co., said “the right of the negroes had been tried and the Court had decreed that they should be sold.” Mr. Goven also said he would “warrant and defend the rights, title, secure possession to the purchasers.” The sale was ordered to proceed.[7]

Rather than being sold individually, the 29 enslaved men, women and children were divided into two lots distinguished as the “Yellow Breed” and the “Black Breed.” The first group consisted of Patt, who was the styled “ancestress of the rest” and her 13 descendants named Poll, Jerry, Daniel, Aquila, Margaret, John, Harry, Nan, Edy, Martin, Harry, Lewis and Moses. The second group included Hannah whose “descendants have increased” to include [missing]aly, Aron, Solomon, Aggy, Binah, Jacob, Ned, Polly, George, Lett, Judith, Gilbert, Hal, Sall and Tom.

Patt and Hannah, now matriarchs of their own families, were the women who were lent to Sarah (Hudson) Holland for her lifetime by her father’s 1745 will. When the auction took place in 1774, Patt and Hannah had been enslaved by Richard and Sarah Holland for three decades – and by her father before then.

As it turned out, Patt and Hannah and their descendants would be enslaved by the next generation of Hollands. Both lots were purchased by Mr. Dick Holland “agreeable to the terms of the sale” and were “warranted to the purchaser by the said Goven.”[8] Richard “Dick” Holland was the eldest son of Richard and Sarah (Hudson) Holland.[9] To cover his bid Dick Holland gave bonds – meaning he financed it. For his debt to Pleasants (£74.12.11 ½ plus interest & costs), he gave a bond for £125 to George Holland[10] and Richard Anderson.[11] They must have paid Pleasants and Holland repaid them because we never hear any more about it.

Then Dick Holland, George Holland and Richard Anderson bound themselves jointly and severally to Andrew Cochran & Robert Donald & Co., with three bonds including one due on the 6th day of March 1776 for [missing]; a second due on the 6th day of March 1777 for £115 and a third due on [missing]th day of March 1778 for £114.13.8 ½ with interest from 9th day of July 1773. While the first amount due is missing, it was probably about £115 making the total about the £343.3.8 ½ Richard Holland owned them.[12]

The son was assuming the debt of the father. And for the time being, the enslaved remained with the Hollands. With respect to Cohran, Donald & Co., it was just the beginning for all of them.

Richard and Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s Children

In 1774, Richard and Sarah (Hudson) Holland were in their mid-50s and had been married for about 30 years. They had three children:

(1) Mary Holland was born about 1746. She married Joseph Hughes in Louisa County, Virginia in 1767. Shortly thereafter they moved to Rowan County, North Carolina where they remained for the rest of their lives. They had several children and named their first-born son Hudson Hughes.

(2) Richard “Dick” Holland was born about 1750. In 1774 was in his early 20s and unmarried.

(3) Christopher “Kitt” Hudson Holland was born about 1760 thus was about 14 years old in 1774.

Given the span of their birth years, one wonders how many other children Richard and Sarah may have lost as was so common back then.

The Move to Prince Edward County

By the fall of 1776 Dick Holland and presumably the 29 enslaved people he purchased, had moved from Louisa County to Prince Edward County where on 24 September he signed a legislative petition from county inhabitants asking for disestablishment of the Church of England.[13] This was a fairly common type of petition at the outset of the Revolutionary War.

Dick Holland joined the Patriot cause and was appointed an Ensign for the Prince Edward County Militia by the County Court at its May 1777 session.[14] In March 1779, he was recommended as a Lieutenant of the Militia in room of George Booker[15] and in August 1779, he was appointed a Captain of the Militia by the Prince Edward County Court in room of the late Henry Walker, who was killed in battle.[16]

Battle of Guilford Courthouse [17]

In 1937, Mrs. J. L. Bugg, Historian of the D.A.R. Chapter in Farmville, Virginia and Miss Maggie Hix and Mr. Wilson Hix, owners of the “old Walker farm” in an interview concerning the gravesite of Richard “Dick” Holland, shared a story about he and Henry Walker:

“It is said that before Capt. Walker died he requested a pencil and paper, wrote a note to his young wife and had this wrapped and tied to the bridle of his horse. The horse was then turned loose to come home. One night the young wife, hearing a noise at the door, went out and found her husband’s horse standing there with the note[18] for her. Capt. Holland evidently admired Mrs. Walker very much as he remarked to some of his brother officers, that if he lived to the end of the war, that he was going to marry the widow of his beloved Capt. Walker. This he did after two years of courtship. When death came to him he was buried in the old Walker burying ground.”[19]

The story may be romanticized, but Dick Holland did, in fact, marry Henry Walker’s widow, who was Martha Jones, daughter of William & Lucy (Anthony) Jones of Buckingham County, Virginia. They had several children including their eldest son Henry Walker Holland named after his friend the “beloved Captain Walker” and of course, her first husband.

The youngest son Christopher Hudson Holland married his first cousin once removed Frances “Fanny” Anderson, daughter of Richard Anderson and his first wife Mary Goodwin. Richard Anderson was a son of Pouncey and Elizabeth (Holland) Anderson, she being Dick & Christopher Holland’s paternal aunt. Christopher “Kitt” & Fanny Holland also lived in Prince Edward County. They named their first daughter for her grandmother Sarah Hudson Holland.

Richard & Sarah (Hudson) Holland in Prince Edward County, Virginia

Richard and Sarah (Hudson) Holland’s whereabouts from 1774-1780 are unknown. I searched extant tax lists and order books for the Virginia counties of Albemarle, Amelia, Hanover, Henrico, Louisa and Prince Edward, but was unable to find them. They may have been in Rowan County, North Carolina with their daughter. An 1802 lawsuit alleges that in 1774 Dick Holland conspired with his parents to remove some of their enslaved people out of state to prevent their sale.[21] That same allegation was made in the Pleasants suit filed back in the late 1760s against Richard and Sarah Holland.[22] Rowan County with their relatives seems like the logical place.

They eventually resurfaced in Prince Edward County, Virginia where on 13 May 1780 he made his will and styled himself “Richard Holland of the County of Prince Edward.” He appeared on Prince Edward County personal property tax lists for 1782 and 1783 but does not appear on land tax lists for those years.[23]

Year Person White Tithables Slaves 16+ Slaves <16 Horses Cattle

1782 Richard Holland 1 5 10 5 19

1783 Richard Holland 2 5 8 5 12

Their son Dick Holland is also found on the 1782 Prince Edward County land tax list paying on 776 acres.[24] This land was on Vaughan’s Creek. I found no deed where Dick Holland bought this land. It came from his grandfather Charles Hudson, who lent it to Sarah (Hudson) Holland for life. Dick Holland and his brother Christopher Holland later jointly owned this tract (after their mother’s death) and hired Robert Venable to survey and divide it.[25]

Dick Holland also appears on the 1782 and 1783 personal property tax lists:[26]

Year Person White Tithables Slaves 16+ Slaves <16 Horses Cattle

1782 Dick Holland 1 5 6 7 18

1783 Dick Holland 1 10 17 15 78

Note that eight years after the 1774 public auction where Richard and Sarah Holland had lost nearly everything they owned, somehow they still managed to have 13 -15 enslaved people. Dick Holland’s increase in the number of enslaved from 11 to 27 makes me wonder if this is when he brought people back from out of state. Most of the enslaved must have been Patt and Hannah and their descendants.

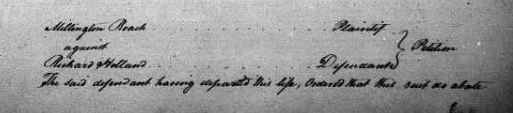

The Death of Richard Holland

Richard Holland was dead by 20 April 1784 when a suit against him by Millington Roach was abated. The court noted the suit was abated because “the said defendant having departed this life.”[27]He was about 66 years old.

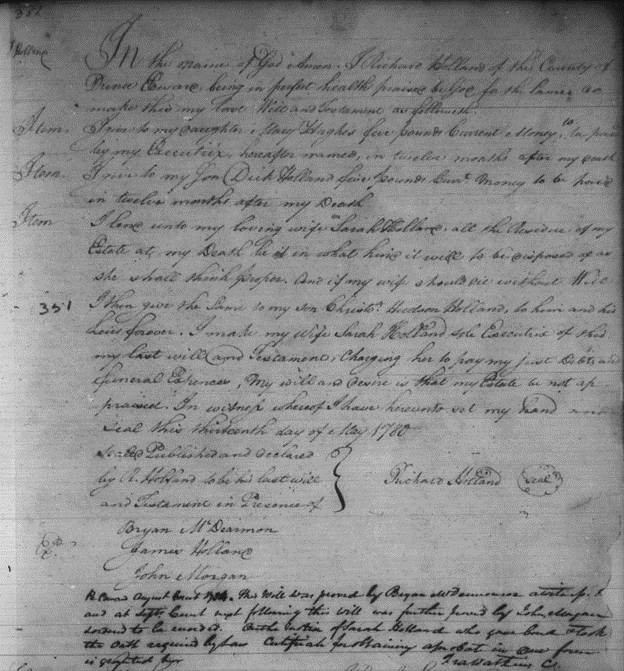

His will was proven at the August 1784 Prince Edward County Court.[28] A transcription follows:

In the name of God Amen. I Richard Holland of the County of Prince Edward being in perfect health praised by God for the same so make this my last Will and Testament as followeth. I give to my daughter Mary Hughes five pounds Current Money to be paid by my Executrix hereafter named, in twelve months after my Death. I give to my son Dick Holland five pounds Currt Money to be paid twelve months after my Death. I lend unto my loving wife Sarah Holland, all the Residue of my Estate at my Death be it in what kind it will to be disposed of as she shall think proper. And if my wife should die without Will then I give the same to my son Christor Hudson Holland, to him and his heirs forever. I make my wife Sarah Holland sole Executrix of this my last will and Testament, charging her to pay my just Debts and funeral expenses. My will and desire is that my Estate not be appraised. In witness whereof I have hereunto set my hand and seal this thirteenth day of May 1780.

Sealed Published and Declared Richard Holland (seal)

By R. Holland to be his last will and Testament in Presence of

Bryan McDearmon, James Holland, John Morgan

Prince Edward County August Court 1784. This will was proved by Bryan McDearmon (illegible) and at Sept Court next following this will was further proved by John Morgan (illegible) to be recorded. Oath (illegible) of Sarah Holland who gave bond & took the oath required by Law. Certificate for obtaining (illegible). Francis Watkins, Clerk.

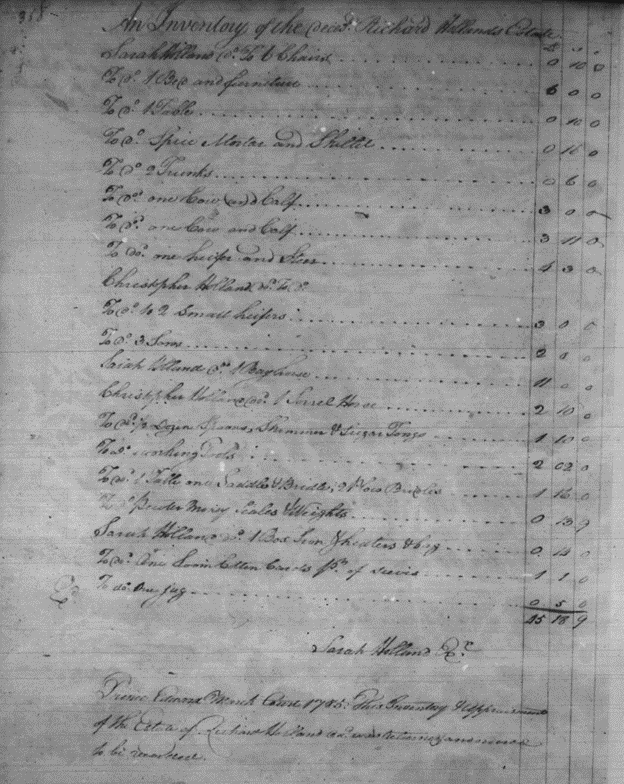

Widow and Executrix Sarah Holland filed an Inventory of Richard Holland’s estate with the Prince Edward County Court at their March 1785 session.[29]

An Inventory of the Dec’d Richard Holland’s Estate

Sarah Holland £ s p

To Do 6 Chairs 0 10 0

To Do 1 Bed & Furniture 6 0 0

To Do 1 Table 0 10 0

To Do Spice Morter & Skillet 0 16 0

To Do 2 trunks 0 6 0

To Do one cow and calf 3 0 0

To Do one cow and calf 3 11 0

To Do one heifer & Steer 4 3 0

Christopher Holland

To Do two small heifers 3 0 0

To Do three sows 2 0 0

Sarah Holland 1 bay horse 11 0 0

Christopher Holland 1 sorrel horse 2 10 0

To Do 1/2 dozen spoons, skimmer & sugar tongs 1 10 0

To Do working Tools 2 2 0

To Do 1 Table, one saddle & bridle, 2 Plow Bridles 1 16 0

To Do Pewter Money scales & weights 0 13 9

Sarah Holland 1 box Iron & heaters & bag 0 14 0

To Do One Loom Cotton Cords 1 pr of sieves 1 1 0

To Do one jug 0 5 0

45 18 9

Sarah Holland, Executrix

Prince Edward Court March 1785. This Inventory & Appraisement of the Estate of Richard Holland, dec’d was returned & ordered to be recorded.

Richard Holland’s inventory amounted to just £45.18.9 – a far cry from where he and Sarah began married life in Henrico County some forty years earlier. From his will and his inventory, it is evident he held no enslaved people in his own right at the time of his death. That does not mean, however, that his family did not continue to benefit from the labor of enslaved people.

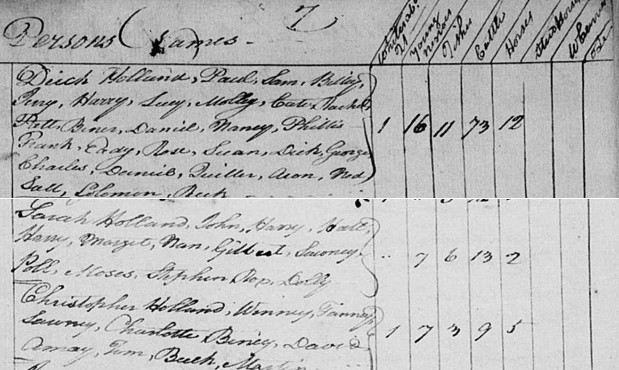

Patt and Hannah, daughter of Judy and Their Descendants

With Richard Holland now dead, his wife and sons appear on the Prince Edward County Personal Property Tax List for 1784 and 1785.[30] While not the case for most years, the names of the enslaved people they held for both years are provided. The descendants of family matriarchs Patt and Hannah are still found among the names of the enslaved a decade after they were purchased by Dick Holland. They are in bold. It appears that Patt is still alive [with Dick Holland], but that Hannah, daughter of Judy has died. No doubt there are children listed here whom are descendants of Patt or Hannah – or both – who were as yet born in 1774.

1784 – Dick Holland held 28 enslaved people named Paul, Sam, Billy, Jerry [Patt], Harry [Patt], Lucy, Molly, Cate, Rachael, Patt [Patt], Biner [Hannah], Daniel [Patt], Nancy, Phillis, Frank, Edy [Patt], Rose, Susan, Dick, George [Hannah], Charles, Daniel [Patt], Quillen/Aquila [Patt], Aron [Hannah], Ned [Hannah], Sall [Hannah], Solomon [Hannah] and Beck, 10 of whom were 16 years or older.

1785 – Dick Holland held 30 enslaved people named Paul, Billy, Lucy, Moll, Rachael, Beck, Nanny/Nan, Chilles, Frank, Roger, Allen, Sarah, Dick, George [Hannah], Charles, Daniel [Patt], Jean, Jan, Deavy, Harry, Quillen/Aquila [Patt], Daniel [Patt], Patt [Patt], Binah [Hannah], Nead/Ned [Hannah], Aaron [Patt], Sall [Hannah], Solomon [Hannah] and Kate.

1784 – Sarah Holland held 13 enslaved people named John [Patt], Harry [Patt], Hall/Hal [Hannah], Harry [Patt], Margaret [Patt], Nan [Patt], Gilbert [Hannah], Sawney, Poll [Patt], Moses [Patt], Stephen, Rox and Dolly, six of whom were 16 years or older.

1785 – Sarah Holland held 15 enslaved people named John [Patt], Harry [Patt], Hall [Hannah], Margaret [Patt], Nan [Patt], Hannah [Hannah], Gilbert [Hannah], Martin, Sonney, Polley/Poll [Patt], Moses [Patt], Stephen, Rolay [Raleigh], Dolly and Margaret [Patt].

1784 Christopher Holland held 10 enslaved people named Winney, Fanny, Sawney, Charlotte, Biney, David, Amey, Tom [Hannah], Buck and Martin two of whom were 16 years or older.

1785 – Christopher Holland held six enslaved people named Winnie, Jerry, Sonny [Sawney], Amey, Tom [Hannah] and Buck.

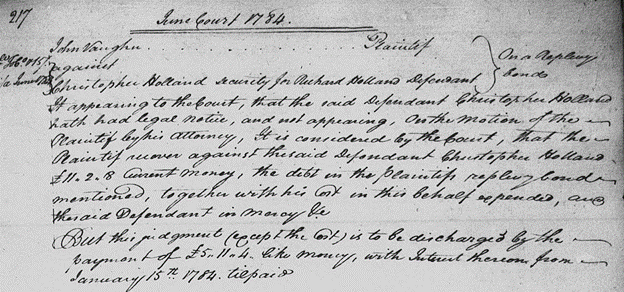

Death Does Not Bring Relief from Debt and Lawsuits

Richard Holland’s debts continued to chase him beyond his death. John Vaughan, whose case against him was abated by his death, brought suit against Richard Holland’s son Christopher Holland who was security for the debt. Christopher Holland failed to appear at the June 1784 Court session and the plaintiff was awarded £11.2.8 and his costs, which amounted to £95 lbs of tobacco. The Court further ordered that the judgement (except the costs) could be discharged by paying £5.11.4 with interest from 15 January 1784 until paid.[31] Mentioned is a replevy [replevin] bond, which was a court-assisted repossession of property and was an alternative to a detinue action in that the plaintiff could take possession of property prior to trial of the suit. A detinue action was to recover property unlawfully kept by a defendant rather than the act of taking property. This was often used by creditors to recover property pledged by a debtor but not delivered.[32]

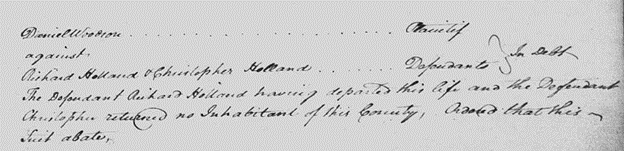

Later in the June Court session Daniel Woodson sued Richard and Christipher Holland for a debt. The suit was abated noting that Richard Holland had died and Christopher Holland was not an inhabitant of the county.[33]

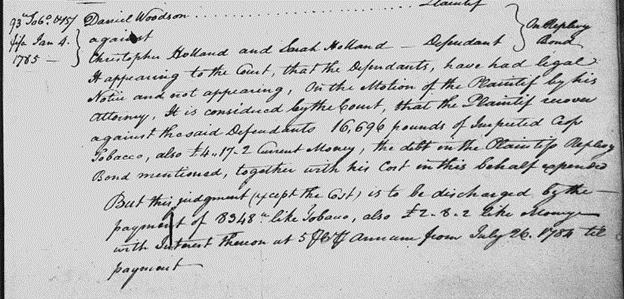

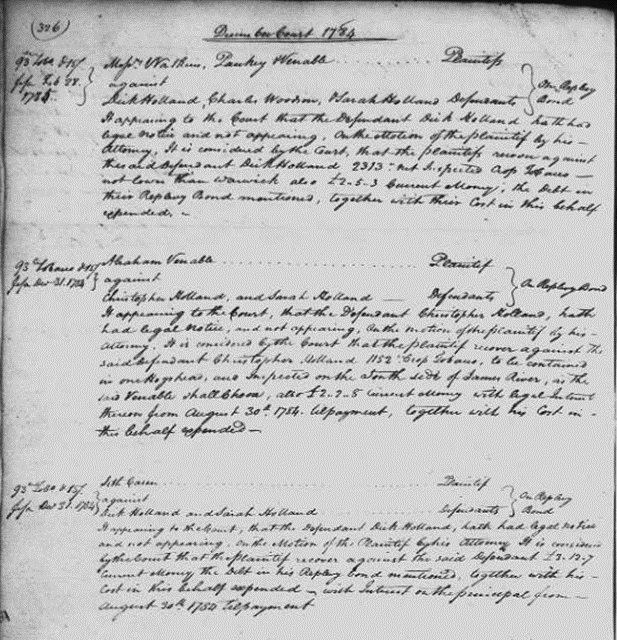

After Richard Holland’s death, Woodson revived his former suit by going after his sons Dick and Christopher Holland and their mother Sarah (Hudson) Holland. They failed to appear at the November 1784 Court and defaulted. The Court awarded Woodson 16,696 lbs of tobacco and £4.17.2 the debt on the bond. The Court allowed that the judgement could be discharged by paying 8,348 lbs of tobacco and £2.8.2 plus the plaintiff’s costs to bring the suit.[34]

At the December 1784 court, the Hollands failed to appear to answer three debt suits and defaulted. Messrs. Watkins, Pankey and Venable were awarded 2,313 lbs of tobacco plus £2.5.3, Abraham Venable was awarded 1,152 lbs of tobacco plus £2.2.8 and Seth Casen was awarded £3.12.7. Interest and costs to bring the suit were also awarded.[35]

In April 1790, George Holland [either Richard Holland’s brother or nephew] sued Dick Holland complaining that he owed him £600 specie. George Holland asserted that Dick Holland acknowledged the debt at Louisa County Court on 20 December 1781. On 30 January 1786, a conditional order against Dick Holland his security Massannello Womack who was noted to have made a payment of an unknown amount in April 1786. The case was continued multiple times in 1787, 1788 and 1789. In 1790, a judgement was granted for £600 specie. The court then allowed that the judgement could be discharged by Holland paying £164.16.9 with interest at 5 percent per annum from 16 January 1783 until paid. George Holland agreed to stay the judgment until the following January. He also acknowledged the debt was reduced by £109.17.6, which had been paid. Evidence entered included a 20 December 1781 statement from Dick Holand and Richard Holland (his father) that they owed George Holland £300 lbs specie or the value thereof in good merchantable tobacco at Manchester of Shockoe’s Inspection at or before 10 June 1782 under penalty of £600 specie. On 16 January 1783, George Holland also acknowledged that he had received of Dick Holland part of the debt within John Webb’s bond payable to Miles Selden attorney for Joseph Mayo for14,500 lbs tobacco at 26/ p hundred.[36]

The Death of Sarah (Hudson) Holland

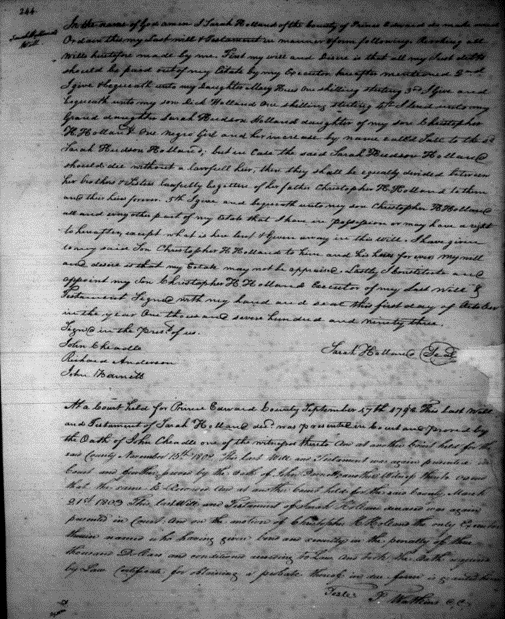

Sarah (Hudson) Holland made her will on 1 October 1793.[38] While it was not partially proven in court until 17 September 1798, Sarah apparently died about 1795, the last year she appeared on the Prince Edward County personal property tax rolls.[39] A transcript of her will follows:

In the name of God Amen. I Sarah Holland of the County of Prince Edward do make and Ordain this my last will and Testament in the manner of form following. Revoking all wills heretofore made by me. First my will and desire is that all my just debts should be paid out of my Estate by my Executors herein mentioned. 2nd I give and bequeath unto my Daughter Mary Hues one shilling sterling. 3rd I give and bequeath to my son Dick Holland one shilling sterling. 4th I lend unto my granddaughter Sarah Hudson Holland daughter of my son Christopher H. Holland one Negro girl and her increase by name called Sall to the said Sarah Hudson Holland, but in case the said Sarah Hudson Holland should die without a lawfull heir, then they shall be equally divided between her brothers & sisters lawfully begotten of her father Christopher H. Holland to them in their heirs forever. 5th I give and bequeath unto my son Christopher H. Holland all and every other part of my Estate that I have in possession or may have a right to hereafter, except what is here lent & given away in this will. I have given to my said Son Christopher H. Holland to his and his heirs forever. My will and desire is that my Estate not be appraised. Lastly, I constitute and appoint my Christopher H. Holland Executor of my last will and testament. Signed with my hand and seal this first day of October in the year one thousand seven hundred and ninety three.

Signed in the presence of us:

John Cheadle, Richard Anderson, John Barnett Sarah Holland (seal)

At a Court held for Prince Edward County September 17th 1798 this last will and testament of Sarah Holland decd was presented in Court and proved by the Oath of John Cheadle one of the witnesses thereto And at another Court held for the said County November 15th 1802 this last will and testament was again presented in Court and further proved by the Oath of John Barnett another witness thereto Ordered that the same be Recorded and at another Court held for the said County March 21st 1803 this last will and testament of Sarah Holland deceased was again presented in Court And on the motion of Christopher H. Holland the only Executor therein named who having given bond and security in the penalty of three thousand dollars and conditioned according to Law. And took the Oath required by Law. Certificate for obtaining a probate thereof in due form is granted.

Teste F. Watkins C.C.

Both Richard and Sarah (Hudson) Holland directed that their estates were not to be appraised. While Sarah filed an Inventory for her husband, none was done so for her. Perhaps debt was the reason she did not want an accounting of what enslaved people she held.

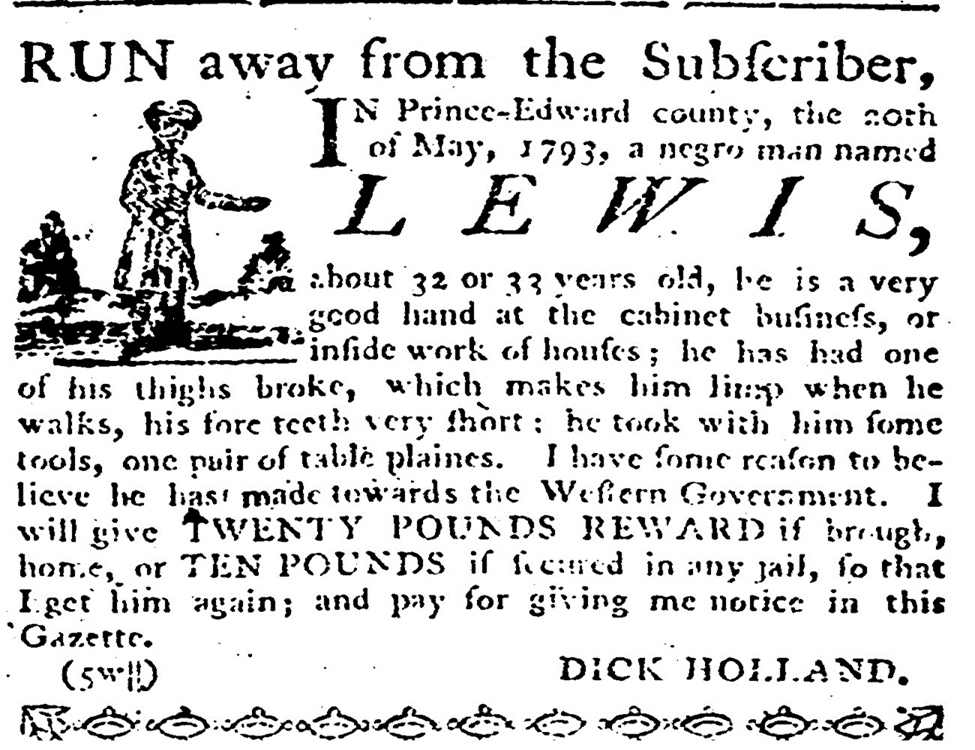

Next time: With the death of Sarah (Hudson) Holland removing a major legal incumbrance to forcing the sale of the enslaved, Cochran & Donald reemerges to try and collect their debt from the Hollands. Dick Holland is sued by his siblings to divide their mother’s estate. We also learn what really happened at the 1774 public auction.

[1] Cochran & Co. is just one of the several iterations of the Glasgow and later London merchant company to which the Hollands were in debt. This reflects the changing partners over half a century. Donald, Cohran & Co. and other forms are used in this post consistent with the period records.

[2] Bill of Dick Holland sworn in open court 26 November 1800, Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[3] “A Slave Auction in Virginia”, Slavery Images: A Visual Record of the African Slave Trade and Slave Life in the Early African Diaspora, accessed September 5, 2023, http://www.slaveryimages.org/s/slaveryimages/item/2226

[4] Slave Auctions, Selections from 19th-century narratives of formerly enslaved African Americans, National Humanities Center Resource Toolbox: The Making of African American Identity: Vol. 1, 1500-1865; https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai/enslavement/text2/slaveauctions.pdf

[5] Per Dick Holland the auction was held in March 1774. Bill of Dick Holland sworn in open court 26 November 1800, Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[6] Joseph Lewis married Ann Hudson sister of Sarah (Hudson) Holland.

[7] Dabney Miller deposition taken 25 December 1801. Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[8] Dabney Miller deposition taken 25 December 1801. Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[9] Bill of Dick Holland sworn in open court 26 November 1800, Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[10] Likely his first cousin George Holland, son of his father’s brother of the same name or perhaps his first cousin George Holland, son of Michael & Phoebe (Winn) Holland of Amelia County.

[11] Likely his first cousin Richard Anderon, son of Pouncey and Elizabeth (Holland) Anderson. Less likely his first cousin Richard Anderson, son of Michael & Sarah (Meriwether) Anderson.

[12] Donald & Cochran & Co. v. Holland, 1796. U.S. Circuit Court, 5th circuit, cases ended 1791-96, restored, Miscellaneous Reel 666-667 B-F, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[13] Prince Edward County, Virginia Inhabitants: Petition. N.p., 1776, Library of Virginia Digital Collection, https://lva.primo.exlibrisgroup.com/discovery/fulldisplay?docid=alma9917819581005756&context=L&vid=01LVA_INST:01LVA&lang=en&search_scope=MyInstitution_noAER&adaptor=Local%20Search%20Engine&tab=LibraryCatalog&query=any,contains,Prince%20Edward%20County&sortby=date_a

[14] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 6 Part 2 1771-1781, p. 512; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9YM5?i=281&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[15] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 6 Part 2 1771-1781, p. 20 Section 2; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9TP4?i=300&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[16] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 6 Part 2 1771-1781, p. 47 Section 2; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9T1G?i=313&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[17] McBarron, H. Charles. Battle of Guilford Courthouse, 15 March 1781, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

[18] Unfortunately, the record does not include the contents of Henry Walker’s note.

[19] Paulette, E. Lewis. et al. Capt. Richard Holland’s Grave : Survey Report, 1937 June 3. N.p., 1937. Print, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[20] (1805) A Receipt for Courtship. England, 1805. London: published by Laurie & Whittle. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/96512570/.

[21] Holland v. Donald, Cochran & Strange (ended 1802) – U.S. Circuit Court, 5th Circuit, Richmond, Virginia, Ended Cases, restores 1801-1804, Box 18; Barcode 7420925, Stack 4, Area B, Row 70, Section 1, Shelf 4, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia.

[22] Pleasants v. Holland & Cochran & Co. Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia, Louisa County, Virginia Chancery Suit 1773-010; https://www.lva.virginia.gov/chancery/case_detail.asp?CFN=109-1773-010; accessed 2 September 2023

[23] Prince Edward County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Lists,1782-1809; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS79-1SK5-1?mode=g&cat=693155; accessed 21 August 2023

[24] Land Tax Books Prince Edward County 1782-1810, Reel 251, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia

[25] Robert Kelso v. Christopher H Holland, Prince Edward County, Virginia Chancery Suit 1818-021, Virginia Memory, Library of Virginia.

[26] Prince Edward County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Lists,1782-1809; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS79-1SK5-1?mode=g&cat=693155; accessed 21 August 2023

[27] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 7 1782-1785, p. 189; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9Y6H?i=462&cat=375513 ; accessed 9 August 2023

[28] Prince Edward County Will Book 1 (1754-1785), Reel 15, p. 351, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[29] Prince Edward County Will Book 1 (1754-1785), Reel 15, p. 358, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[30] Prince Edward County, Virginia Personal Property Tax List 1782-1809; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS79-1SVG-W?i=280&cat=693155; accessed 22 July 2023

[31] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 7 1782-1785, p. 217; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9YZ6?i=476&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[32] Baird, Robert W. Bob’s Genealogy File Cabinet, https://genfiles.com/articles/colonial-legal-terminology/

[33] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 7 1782-1785, p. 227; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9YDJ?i=481&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[34] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 7 1782-1785, p. 307; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9Y8W?i=523&cat=375513; accessed 9 August 2023

[35] Prince Edward County, Virginia Orders No. 7 1782-1785, p. 326; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS4N-9YD5?i=533&cat=375513 ; accessed 9 August 2023

[36] Prince Edward County, Virginia, Records at Large District Court 1789-1792, p. 67; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CSKK-LSK6-X?i=42&cat=752995; accessed 19 August 2023

[37] The Virginia Gazette and General Advertiser, May 28, 1794, Richmond, VA, Vol: VIII, Issue: 411, Page: 4

[38] Prince Edward County Will Book 3 (1795-1807), Reel 15, p. 244, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[39] Prince Edward County, Virginia Personal Property Tax Lists,1782-1809; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-CS79-1SK5-1?mode=g&cat=693155; accessed 21 August 2023