Most of my Colonial Virginia ancestors did not leave wills. Not only were most people illiterate, but it was customary to wait until you were on your deathbed to make a will. Not surprisingly, this led to many people dying without a making a will. Fortunately for genealogists and family historians, the law prescribed how real and/or personal property was to be distributed absent a will. Part of the probate process was to conduct and inventory and appraise the deceased’s personal property.

Generally speaking, when a person died the spouse or other heirs would go to the local court to be appointed either executor (if the deceased left a will) or administrator (no will) of the estate. The local court would appoint a few local men to conduct an inventory and appraisal (I&A) of the personal property of the deceased. That I&A would then be filed with the court and recorded.

Those interested in learning about their ancestors would do well to study their ancestors’ I&As. Not only can they help prove relationships, but they also provide a list of items our ancestors used in their daily lives. With scant other records sometimes available, the I&A may be the most detail you get about someone’s life and help paint a picture. I&As can give us an idea of economic status, occupation, and the variety of furniture and tools they used to try and maintain the largely self-sufficient existence required for common folk to survive.

Once in a while these records reveal something a bit more unusual, which is the case with my 7x great-grandfather Charles Atkinson.

Origins of Charles Atkinson

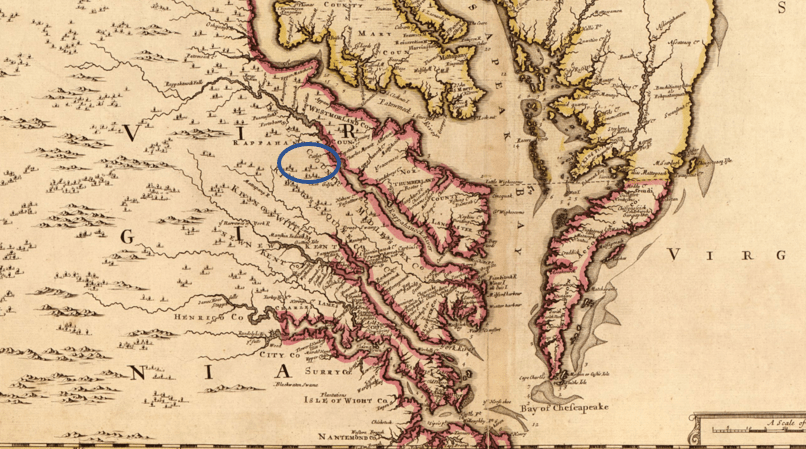

Charles Atkinson lived in the part of Old Rappahannock County, Virginia on the southside of the Rappahannock River that became Essex County in 1692.[2] The lack of any extant record connecting Charles Atkinson or his sons to any other early Atkinson, suggests that he was an immigrant. Given his lack of land ownership and small estate, he likely came to Virginia as an indentured servant.

Perhaps he is the Charles Adkinson referenced as one of 40 headrights claimed by James Boughan, Jr. and John Boughan, who jointly received a patent for 2,000 acres in Essex and King & Queen Counties dated 2 May 1705.[4] While this 1705 patent was issued 17 years after he first appears in the Virginia record, according to a Library of Virginia research note concerning the headright system, significant delays in issuing patents could and did occur. The note provides, in part, “there are instances in which several years elapsed between a person’s entry into Virginia and the acquisition of a headright and sometimes even longer between then and the patenting of a tract of land.”[5] Perhaps coincidentally, Charles Atkinson’s son, John Atkinson, later rented a farm in Essex County from Augustine Boughan, son of John Boughan above.[6]

The Atkinson surname is of Northern English origin deriving from the personal name Atkin – a pet form of Adam. The Scottish equivalent is Aitchison.[7] As Northern England and Scotland share a boarder Charles Atkinson was either English or Scottish – much more likely the former given the European make up of Virginia at the time. He was probably born in the mid-1660s in England, immigrated to Virginia in the mid-1680s, served an approximate four-year term of indenture, became a tenant farmer, married in the early 1690s and had four children before he died about 1702 in his late 30s leaving a widow and four young children.

Virginia Records for Charles Atkinson

As mentioned earlier the extant records often do not provide much information about a particular ancestor. That is true with respect to Charles Atkinson:

He first appears in the Virginia record in Old Rappahannock County when he witnessed a deed on 31 January 1688 between Humphrey Booth, planter and Samuel Griffin, shipwright.[8] This deed was rerecorded in Essex County on 22 November 1697.[9]

At Essex County court held 10 July 1694, John Seymore was in court defending himself against a charge by Richard Rhodes that “about the last of March 1693” that “Seymore did unlawfully kill a hog of Charles Atkinsons.” The case noted that Rhodes was seeking the £1000 informer’s fee set forth by the General Assembly. Seymore, through his attorney, argued that there was no evidence presented other than what was said in court. The Court granted his motion for dismissal of the case.[10]

On 10 August 1697 Thomas Hucklescott was deposed and testified that he was at William Cole’s house and saw John Williams and Charles Atkinson there. Hucklescott testified that he was asked to write an agreement between Williams and Atkinson to share equally in the losses or gains from the suit in which John Williams alleges that John Hawkins stole several thousand tobacco plants of the said Williams.[11]

On 10 June 1701, the will of William Copeland was presented to the Essex County court. Charles Atkinson, Nicholas Copeland, Jr., and Richard Goode bound themselves for £100, as security for Nicholas Copeland, Sr.’s obligation as executor of his son, William Copeland’s estate.[12] The will named his father Nicholas Copeland (Sr.) and his brother Nicholas Copeland (Jr.) as executors.

Charles Atkinson was married to Ann, daughter of Nicholas Copeland, Sr. Their marriage was acknowledged on 11 August 1701, when her father Nicholas Copeland, Sr. gifted “my son and daughter Charles and Ann Atkinson” life use of 100 acres of land in Essex County “on the southside of the Rappahannock River bounded by the land of William Beasley beginning at a marked red oak and running thence NNW 126 ½ poles to a stake by two marked red oaks at the corner of John Dowers line thence SSE 126 ½ poles to a stake thence along the line by Beasley’s land E 126 ½ poles to the corner where it first began.”

Nicholas Copeland (Sr.) directed that after Charles and Ann Atkinson ’s deaths, the land would go to their daughter Mary Atkinson and if she died without heirs it would go to the remaining heirs (unnamed) of Charles and Ann (Copeland) Atkinson.[13] Charles and Ann (Copeland) Atkinson were married about 1694 and had four children including daughter Mary. The other three were sons named Charles, Jr., Nicholas (for his grandfather Copeland) and John Atkinson.

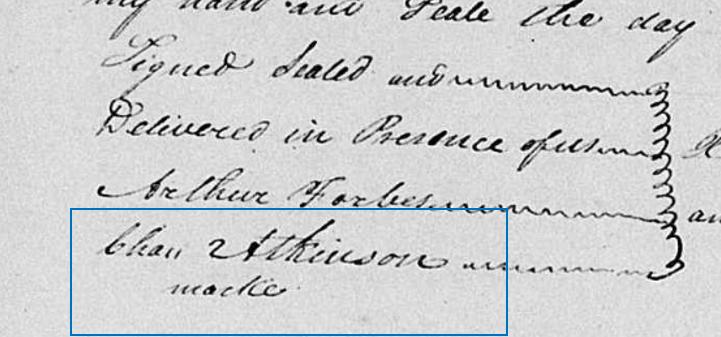

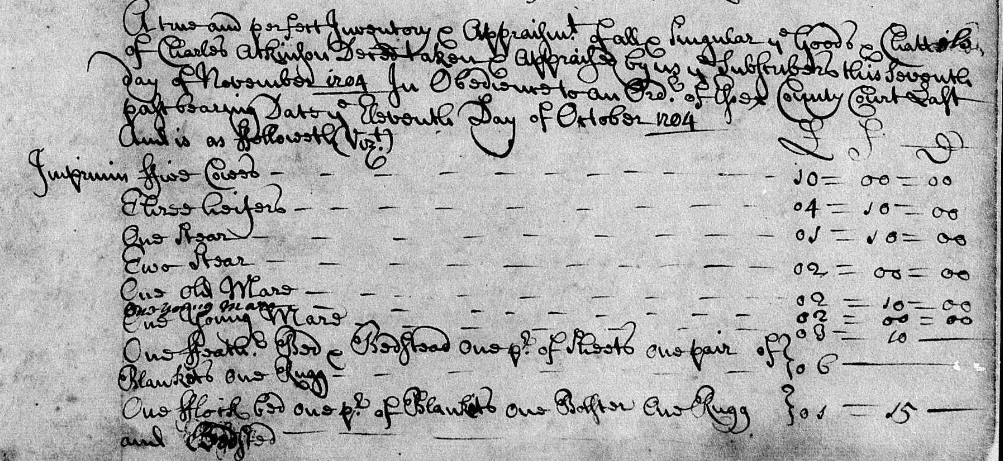

Just two years later, Charles Atkinson’s Inventory was presented by Thomas Phillips and Ann his wife, widow & relict of Charles Atkinson to Essex County Court on 10 September 1703 and was recorded.[14] The Essex Court ordered an inventory and appraisal be conducted, which was done in November 1704.[15]

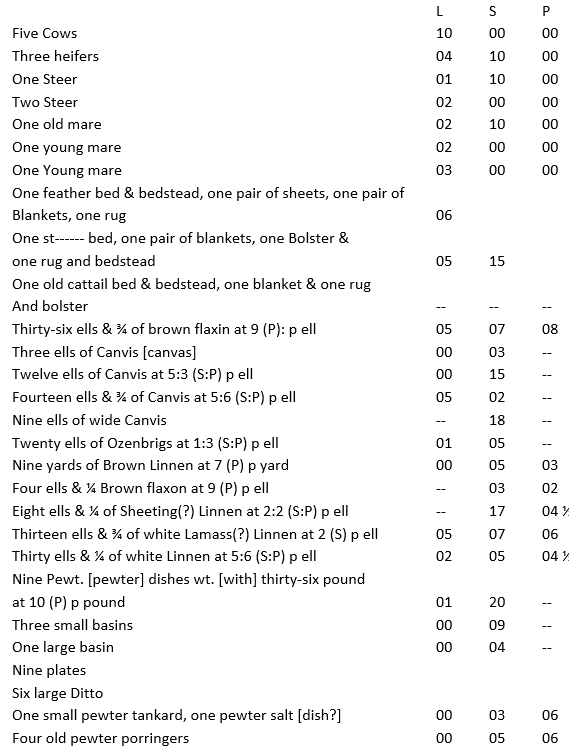

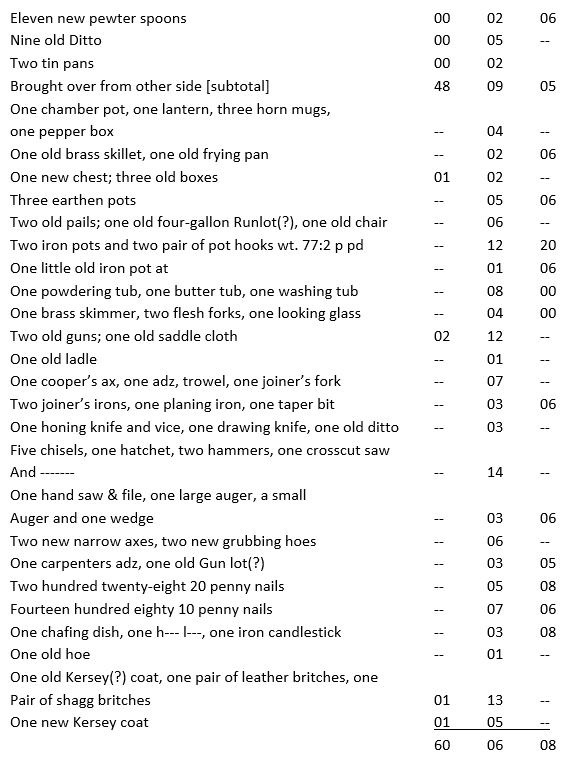

Transcription of Charles Atkinson’s November 1704 I&A (an “ell” is a unit of measurement of about 45 inches or 1 1/4 yards):

What does Charles Atkinson’s I&A tell us about him?

His appraisal amounted to just over £60, which is not a large estate, but he did have luxuries beyond necessity – a feather bed, pewter dishes and looking glass (a mirror). He did not own any books – he and his wife were both illiterate. The inventory contains the normal things one expects to see – livestock, beds and other furniture, cookware and other kitchen utensils, as well as a variety of tools for being self-sufficient in growing and harvesting one’s own food – plant and animal – as well as tools for general maintenance. What strikes me as interesting is the volume of linen and canvas.

Estate inventories often point to a person’s profession – farmer, laborer, carpenter, cooper, tailor, blacksmith, etc. Most of my ancestors were laborers or farmers with an occasional small merchant, blacksmith or carpenter sprinkled in here and there.

Charles Atkinson’s inventory includes more than 440 yards of linen and canvas of varying quality. That was more than one-third of the total estate value. His inventory did not include any spinning wheels or looms. Was he a fabric merchant? Most people used linen to make their own clothes back then. Charles Atkinson lived near a trading post called Hobb’s Hole where the Port of New Plymouth was established in 1682. The name later became (or perhaps more accurately reverted) to Tappahannock – today an incorporated town and the Essex County seat. Did he sell canvas to the several shipwrights mentioned in contemporary records for their use in making or repairing sails? His inventory also had more carpentry tools and certainly more nails than one would expect for general home use. Was he a shipwright?

Charles ATKINSON, b.c. 1665, d.c. 1702, Essex County, Virginia, m.c. 1694, Ann Copeland (bef. 1672- d.c. 1732), daughter of Nicholas and Judith Copeland, issue:

Charles Atkinson, Jr. b.c. 1695 Essex County, VA d, 1761, Essex County, VA

Nicholas Atkinson b.c. 1697 Essex County, VA d. 1773, Essex County, VA

John Atkinson b.c. 1699 Essex County, VA d. 1748 Essex County, VA

Mary Atkinson b.c. 1701 Essex County, VA m. poss. John Landrum[16]

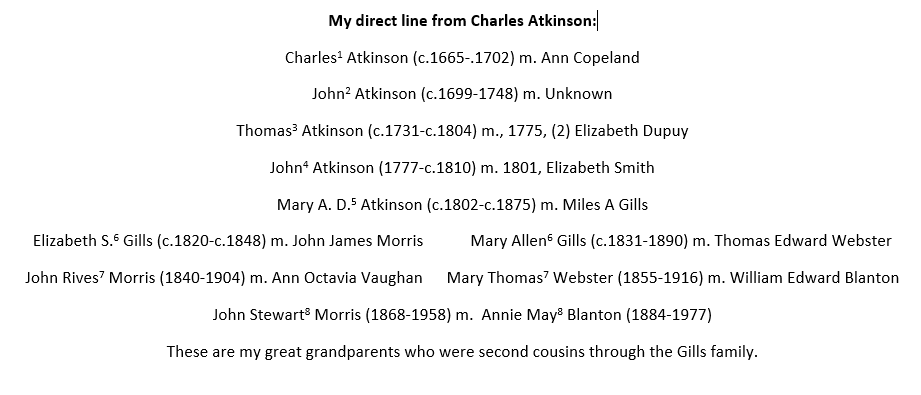

Charles1 Atkinson’s grandson Thomas3 Atkinson is my ancestor who migrated from Essex County to Amelia County about 1748. He was also a merchant and will be the subject of a future blog post.

If you enjoyed this post, please consider subscribing to my blog at https://asonofvirginia.blog/.

[1] Attkison, Atkisson, Adkinson, Adkerson, Akission, Atkerson and a variety of other spellings are found in these records. I have I used the spelling in the record when noting a record and use Atkinson otherwise.

[2] It is called “Old” Rappahannock County because a different present-day Rappahannock County that was created in 1833 out of part of Culpeper County.

[3] Senex, J. (1719) A new map of Virginia, Maryland, and the improved parts of Pennsylvania & New Jersey. [London: s.n] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007625604/.

[4] Nugent, Nell Marion. Cavaliers and Pioneers, Volume III, 1695-1732, p. 92.

[5] Library of Virginia; Headrights (VA-NOTES); https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/guides/va4_headrights.htm; accessed 6 December 2021. They describe the process for obtaining a patent as a multi-step process that one can see might take time to complete. First, the claimant had to obtain a certificate from the county court and then take that to the Secretary of the Colony’s office at the capital to obtain the “headright” or right to patent 50 acres per person brought into the Colony. The claimant then had to take the headright to a surveyor to have a survey made of available land and then he had to take the survey back to the Secretary’s office to obtain the patent.

[6] Sparacio, Ruth and Sam. Essex County, Virginia Will Abstracts 1748-1750, (Millsboro, DE: The Ancient Press Collection from, Colonial Roots, 2016), p. 91

[7] Atkinson Surname – Wikipedia.

[8] (Old) Rappahannock County, Virginia Deed Book 8 (1688-1692), p. 11; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9P6-3WPY?mode=g&cat=413447; accessed 21 January 2022

[9] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book 9 (1695-1699), p. 133; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9P6-3WYK?i=258&cat=413447; accessed 21 January 2022

[10] Essex County Orders 1694-1695, p. 196; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3Q9M-C9T3-PQWK?i=480&cat=413447; accessed 21 January 2022+

[11] Essex County Deed Book 9 (1695-1699), p. 116; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QSQ-G9P6-3WGD?i=250&cat=413447 ; accessed 21 Dec 2021

[12] Essex County Deed Book 10 (1699-1702), p. 83; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89P6-K4S?i=93&cat=413447; accessed 6 December 2021.

[13] Essex County Wills and Deeds, Volume 10 (1699-1702), p. 86; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-89P6-KQH?mode=g&i=96&cat=413447; accessed 6 December 2021.

[14] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book 11 (1702-1704), p. 93; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99P6-2PPY?mode=g&cat=413447; accessed 30 November 2021.

[15] Essex County, Virginia Deed Book 12 (1704-1707), p. 63; https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:3QS7-99P6-2PPY?mode=g&cat=413447; accessed 30 November 2021.

[16] In a deed dated 18 February 1720 and recorded 19 February 1722 in Essex County, Nicholas2 Atkinson purchased 100 acres in Essex County from John and Mary Landrum of Spotsylvania County for 5,500 pounds of “good tobacco in caske.” The deed noted that Nicholas2 Atkinson already lived on the land and that the land was described as bounded by William Beesley (sic) beginning at a marked red oak thence running NNW 126 ½ poles to the corner tree of John Doors (sic) thence E 126 ½ poles to a stake by two marked red oaks at the corner of the said Doors [sic] thence SSE 126 ½ poles to a stake thence along XXXXXXX [“X” marked seven times in record book] the line by Beesley’s land E 126 ½ poles to the corner where it began. Essex County Deed Book 17 (1721-1724), p. 148.This is the same detailed description as the land provided for life to Charles and Ann (Copeland) Atkinson by Nicholas Copeland in 1701, which was to be inherited by their daughter Mary2 Atkinson after the deaths of her parents. This suggests that Mary2 Atkinson, daughter of Charles and Ann (Copeland) Atkinson, inherited or was given that land, married John Landrum, and then sold the land to her brother Nicholas2 Atkinson as the Landrums had moved to Spotsylvania County. Ann (Copeland) Atkinson Phillips was still alive as late as 17 October 1732 when she was the administrator of her own mother’s estate. Ann (X) Phillips, widow, Charles2 Atkinson, and Nicholas2 Atkinson were bound to the Essex Court for £200 pounds current money for Ann Phillips Admx of Ann Copeland, decd. Essex County Will Book 5 (1730-1735), p. 108-109.