I introduced my 2x great grandfather John Rives Morris in an earlier post concerning his unusual death in Amelia County, Virginia, a murder in California, and rumors of his mental illness. Need to catch up? Click here! This post focuses his early life and offers some insight into his later difficulties.

Born into a world of wealth, privilege and future promise

John Augustus Rives[1] Morris was born 2 November 1840 at Cutbanks Plantation, which contained some 900 acres on both sides of the Appomattox River in both Prince Edward and Buckingham Counties. Most of the acreage and the residence were in Prince Edward with less than 200 acres in Buckingham.[2]

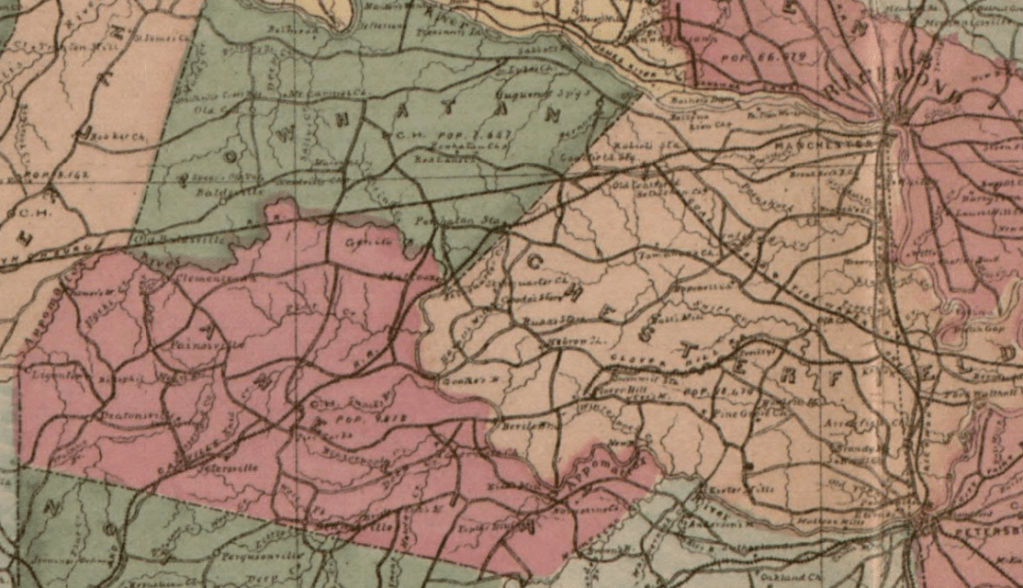

Section of an 1820 Prince Edward County map showing Morris’s Mill along Cutbanks Road and the Appomattox River. Note Buckingham County is directly across the river. Vaughan’s Creek at lower right. (Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia digital collection Prince Edward County, Virginia map 1820)

John Rives Morris was the second child and first son born to John James Morris (called James and styled John J. in most records) and Elizabeth S. Gills[3] who were married about 1837. James’ father, John Morris, in addition to being a planter with land in both Buckingham and Prince Edward Counties, was a long-time Buckingham Justice of the Peace and co-owned a shipping business that transported goods up and down the James and Appomattox Rivers. In 1840, John Morris owned 1136 acres and held 31 enslaved people in Buckingham County. Elizabeth’s father, Miles A. Gills. was similarly situated owning plantations in both Amelia County and Nottoway Counties. In 1840, Gills lived in Amelia and enslaved 54 people – 32 in Amelia and 22 at his plantation in Nottoway County.

In 1836, John Morris gave the Cutbanks property to his son James Morris and three sons-in-law including Nathan H. Thornton (husband of daughter Martha), George W. Motley (husband of daughter Mary) and John W. Yarborough (husband of daughter Helen). By late 1837, James Morris bought out the others and was the sole owner.[4] James’ father also appears to have given James several enslaved persons to work the Cutbanks plantation. Elizabeth (Gills) Morris likely received at least one slave – a personal maid – and perhaps others from her parents at her marriage. In 1830, John Morris held 10 slaves in Prince Edward County, but by 1837, James Morris was paying the tax on eight slaves as well as a carriage, which was very much a luxury item back then. James and Elizabeth would have five children between 1838 and 1846 including daughter Mary Elizabeth Morris (1838), John Rives Morris (1840), Martha Ann “Mae” Morris (1842), William Holland Morris (1844) and Thomas S. Morris (1846).

It was into this world of wealth, privilege and future promise that John Rives Morris was born.

The Wheels Come Off of The Carriage

John Rives Morris’ father James Morris is found on the personal property tax rolls of Prince Edward County from 1837 until 1843. From 1837 until 1842, he held between eight and 11 slaves, a carriage, horses and cattle and paid tax ranging from $7.18 (1838) to $10.10 (1841). Then in 1843 his circumstances changed dramatically. There were no slaves, no carriage, no horses and no cattle and the tax owed was just 14 cents.[5]

An Indenture dated 14 December 1842 was made between John J. Morris [James] and his wife Elizabeth of the County of Prince Edward – 1st part, Nathanial Morris (James Morris’ uncle) of Buckingham County – 2nd part, John Morris (his father), John Jones and Nathan H. Thornton (his brother-in-law) also of Buckingham – 3rd part.[6] The Indenture noted that James Morris owed more than $9,900 plus interest from 1839 until paid. He owed $4,400 to John H. Johnson for whom his father stood security, $2,350 to Carrington, Gibson & Thornton [a store], $2,000 to his father, $700 to Miles A. Gills [his father-in-law] and $500 to Edward Woodbridge.

James Morris expressed his desire to hold his securities harmless and to place into trust with his uncle, Nathaniel Morris, the “752 acres in Prince Edward and Buckingham Counties plus his crop of tobacco, horses, cattle, hogs, household & kitchen furniture, plantation tools, a carriage and harness, two wagons and the rest of his personal property.” The Indenture further provided that James and Elizabeth and their small children were allowed to stay on the land and retain use of the collateral unless the debts were not paid by a date certain when his trustee would sell all of the property listed in the agreement.

The debts could not be paid and the young couple, who by 1844 had at least three children under the age of six, lost Cutbanks Plantation and disappear from the Prince Edward County tax rolls. Interestingly, Cutbanks Plantation is mentioned in an 1871 lawsuit filed against the estate of James’ father, John Morris noting Cutbanks as one of his holdings suggesting that he somehow retained it – perhaps he bought it back at public auction. In 1845, James Morris, now age 33, his wife Elizabeth and, by now four or five young children, were living in Amelia County on a farm owned by his father-in-law, Miles A. Gills.[7]

What happened to this Morris family is partially answered in a Prince Edward County, Virginia Chancery Court file. In 1839, James Morris (using his “legal” name John J. Morris) and his brothers-in law, George R. Motley and John W. Yarborough, brought a suit in the Prince Edward County Chancery Court. When they got Cutbanks Plantation in 1836 they formed a mercantile partnership styled John J. Morris & Company and aimed to restore and enlarge old mill site on the property. They hired Joseph Yarbrough of Halifax County, Virginia to do the work. He was a half-brother of John W. Yarbrough above. Joseph Yarbrough was to provide all materials at a cost equivalent to what would have been paid in the City of Richmond and shipped up the river to Cutbanks. He was apparently bringing said materials from North Carolina. Yarbrough finished the work about August 1837 and presented a bill for $1,154.78. The partners alleged that “the mill had scarcely got into motion before it was manifest that it could answer no good purpose and could grind but indifferently,” so they refused to pay.

Joseph Yarbrough filed suit to collect in the Circuit Superior Court of Law and Equity in Prince Edward County against John J. Morris & Co. demanding the full amount. The partners alleged that during the suit James Morris attempted to get skillful millwrights to ascertain said works to prove his case, but no one wanted to be inconvenienced by spending time as a witness, so they had to go to trial in September 1838 with no expert witness. Joseph Yarbrough was awarded $1,134.56 subject to an abatement of $468.62 leaving a balance of $665.94. The partners asked for a new trial as they believed they could prove the mill was useless as one of the witnesses of the said Joseph Yarbrough [his own brother Richard Yarborough] was willing to examine the mill but they only learned of this after the verdict was rendered. The court did not grant new trial but abated an additional $50 of the award.

The partners then turned to the Chancery Court in May 1839, asking them to grant an injunction so Joseph Yarbrough could not pursue further legal action over the remaining debt, which the court granted. They mention two bonds of $135 each that they wanted to use to offset the balance and asked that 12 months of lost profits of $1,000 be counted as well. James Morris appeared in Lynchburg on 10 May 1839 and made oath that the facts alleged were true.

Joseph Yarbrough filed his Answer in August 1839 disputing the allegations and asking for injunction to be lifted. The aforementioned bonds were apparently for land Joseph Yarbrough bought in Buckingham on installment payments. James Morris paid two of the $135 installments for him, and Yarbrough issued a bond [or bonds] to obligate himself to James Morris for the payments. The Answer further notes that Joseph Yarbrough and his brother, Richard Yarbrough, were partners in a foundry in North Carolina where iron for a mill could be purchased. Joseph Yarbrough appeared in Halifax County in August 1839 to swear his answers true, and the court ordered the injunction lifted the following month. In 1844, another chancery suit was filed in Prince Edward County styled John W. Yarbrough v. John J. Morris, etc. The suit noted that John W. Yarbrough and George R. Motley sold their interest in John J. Morris & Co. to James Morris in November 1837 making him the sole owner.[8] Further records stating the ultimate disposition of these cases were not found, however, it is apparent that it did not end well for James and Elizabeth (Gills) Morris and their children.

A Decade of Death and Changed Circumstances

At just five years old, it’s difficult to know what John Rives Morris understood about the family’s changed circumstances. If he didn’t appreciate it then, he certainly would very soon. Just a few years later, about 1848, death came for his mother Elizabeth and little brother Thomas whose causes of death are unknown. In fact, son Thomas S. Morris is only known to us through an 1847 Deed of Trust between James Morris and his father-in-law Miles A. Gills for the benefit of John Rives Morris and his four siblings Mary, Martha, William H. and Thomas S. Morris. The Trust provided $1,000 to be shared when each child came of age.[9]

By 1850, James Morris and his surviving children had relocated to the City of Richmond, then part of Henrico County. The census taken December 1 for that year includes John J. Morris (James) working as a tobacconist with real estate valued at $5,000. Three Morris children were also living in the household including Mary E., age 12, John A.R., age 10 and Martha, age eight. Son William H. Morris is not listed. Other household members included Morris [Maurice] L. Guerrant, age 28, Mary E. Motley, age 35 (James Morris’ sister), and her children John J. Motley, age 18, George R. Motley, Jr., age 16 and Nancy H. Motley, age six (listed erroneously as Nanny Morris).[10] James Morris was listed a head of household, but this was likely his sister’s home. Mary E.3 (Morris) Motley’s husband, George R. Motley, Sr., is not listed in the census his having died in Richmond, VA in 1848.[11]

Death would come again very soon to the Morris/Motley home. John Rives Morris’ cousin and new housemate George R. Motley, age 17, died of consumption [tuberculosis] on 5 October 1851.[12] Less than two years later, on 2 August 1853, his cousin John J. Motley, age 22, died of the same cause.[13] John Rives Morris’ eldest sister Mary married John Marshall Goddin in 1855 and they lived nearby in Richmond.[14] His father James Morris died about 1857 making John Rives Morris an orphan at 17.[15]

John Rives Morris Goes to Work and to War

After their father’s death, John Rives and sister Martha “Mae” moved in with their brother-in-law and sister, John and Mary (Morris) Goddin.[16] Brother William H. Morris’ whereabouts remain unknown. He is not listed in the 1850 or 1860 census. In 1860, John Rives Morris, now age 20, was working as an overseer at Walker’s factory, a tobacco stemmery located at 12 S. 17th Street and owned by the family of John Stewart Walker. John Rives was an overseer and in that capacity would have managed a gang of enslaved laborers.

In early 1861, Virginia political leaders were debating whether or not to follow seven other states and secede from the Union. In early April, at a convention convened for the purpose, Virginia’s political leaders voted 88-45 to remain in the Union. Soon thereafter, Fort Sumter was attacked by the South Carolina Militia and newly elected President Lincoln called for troop to be sent by the remaining states to put down the rebellion. The call for troops changed public sentiment and Virginia political leaders voted to secede from the Union.

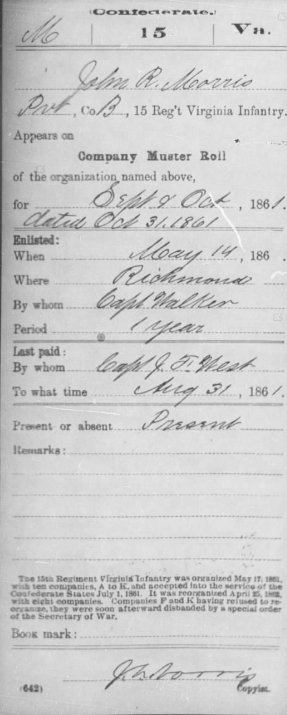

On 14 May 1861, John Rives Morris, age 20, enlisted as a private for a one-year term in the Virginia Life Guard, which had been formed in January of that year. The Guard was soon reorganized and became Company B of the 15th Regiment, Virginia Infantry.[17] Muster roll records note that John Rives Morris was enlisted by Captain John Stewart Walker – his boss at Walker’s tobacco factory.

I have not found any information specifically identifying John Rives Morris as a participant in any particular battle; however, extant muster roll records for July 1861 through February 1862 count him as “present” suggesting that he was consistently with Company B throughout that time. During his time of service, the 15th Virginia Infantry was involved in a number of battles during the 1862 Peninsula Campaign including the Siege of Yorktown (April & May), Battle of Williamsburg (4 May), Battle of Big Bethel (10 June) and the Seven Days Battles occurring from 25 June to 1 July concluding with the 1 July 1862 Battle of Malvern Hill. It was during this last battle that John Rives Morris’ tobacco factory boss and leader of his Company, Major John Stewart Walker (promoted from Captain) was killed.

Written by one of his men many years after the fact, the death of Major Walker was described as follows: “…About one hundred and fifty of our regiment reached the base of the hill, in command of Major John Stewart Walker, formerly captain of the Virginia Life Guard, of Richmond (Company B), who assumed command as soon as Colonel August was placed hors de combat [wounded and out of action]. Here we rested, under severe and continuous fire that did not admit of our raising our heads from the ground. As twilight was deepening into the shades of night, the word was passed down the line to prepare to charge the crest of the hill. Major Walker stood up with drawn sword and flashing eye and gave the command, “Forward, charge!” It was the last word this gallant officer ever uttered. He fell and was dragged into a little branch which flowed at the foot of the hill and expired in the arms of his brother, Captain Norman Walker. Thus, perished as brave a soldier as ever flashed his sword in any cause!”[18] John Rives Morris was almost certainly a witness to major Walker’s death in battle and certainly saw significant action during his service. He was discharged six weeks after the Battle of Malvern Hill on 15 August 1862 and did not serve further during the war.

More Changes in the Family

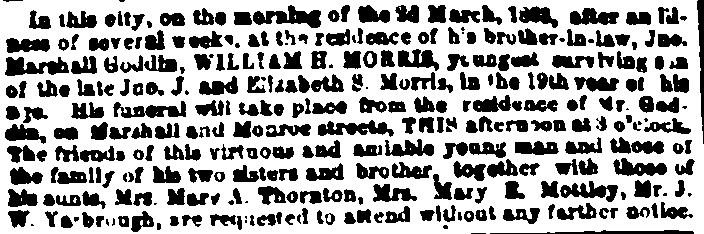

John Rives Morris’ younger brother William Holland Morris finally appears in the record when he enlisted in Company B, 25th Battalion, Virginia Infantry (Richmond Battalion/City Battalion) on 21 January 1863 for the duration of the War. The only muster roll record for him is dated 28 February 1863 and notes him as absent. Under remarks it notes “Not reported – never mustered in.”[19] Why he failed to muster in is revealed in a newspaper article appeared in the Richmond Whig newspaper on 3 March 1863:[20]

On 3 November 1863, his sister Martha Morris would marry[21] her husband, the widowed Colonel John C. Higginbotham of Tazewell County, Virginia who was an officer in Company H, 25th Virginia Infantry.[22] After the war, the Higginbotham’s removed to California.

The Post War Years

Upon the war’s conclusion in April 1865, John Rives Morris signed his required “parole” giving his word he would not take part in hostilities against the United States government. He then took his amnesty oath on 29 April 1865. At that time his address was given as the corner of Marshall and Jefferson Streets in Richmond as his occupation listed as tobacconist.[23] Richmond City Directories for the period indicate he was living with his brother-in-law and sister John M. & Mary (Morris) Goddin whose home was at 401 W Marshall Street and that he was working at Walker’s Factory.

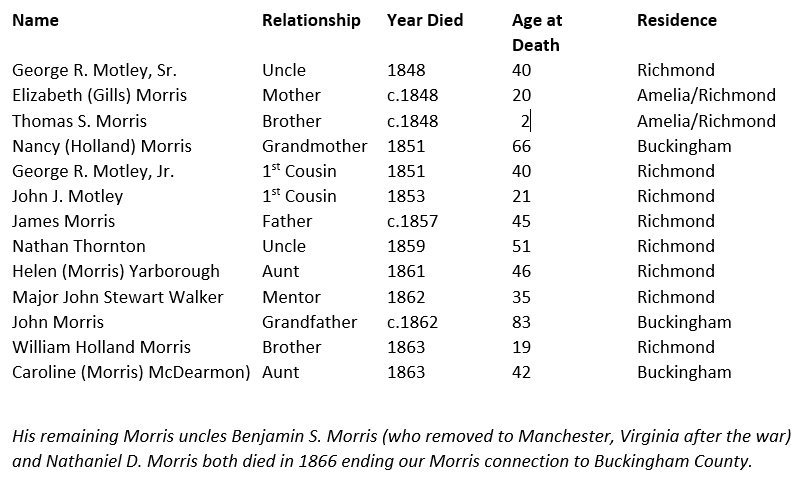

In 1865, John Rives Morris was 25 years old. Thus far his life was one of considerable loss including his home in Prince Edward County, his family’s economic status, and the deaths of his parents and brothers as well as a number of other close relatives:

On top of all of that, he experienced a year of fighting in an infantry unit and witnessed Maj. John Stewart Walker’s death among many others. Of course, he had fought on the losing side and was living in the midst of a decimated Richmond as well as much of the surrounding area. With an economy in shambles and a world seemingly turned upside down, John Rives Morris had to figure out how to make his way in the world.

An Amelia County Romance Blossoms

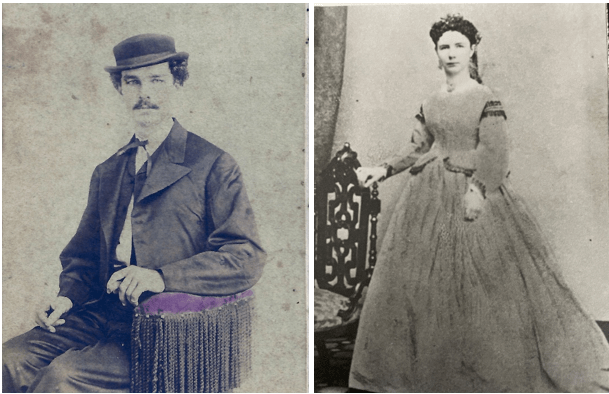

While he grew up in Richmond, John Rives Morris did not lose ties with his Amelia County relatives including his grandparents Miles A. & Mary A. D. (Atkinson) Gills. It was not doubt through his Gills connections that he met his future wife Ann Octavia Vaughan. She was the daughter of Augustus and Mary Spencer (Farmer) Vaughan of Amelia County and an orphan herself by age seven as her parents were both dead by 1851. Ann grew up in the home of her maternal uncle Charles W. Farmer and his wife Alice G. Gills – another daughter of Miles A. and Mary A. D. (Atkinson) Gills – making her the aunt of John Rives Morris. Given the familial connection, the couple may have known each other well before marriage.

In due course John Rives would propose and the couple were married in Amelia County on 18 December 1867. The couple would initially live in Richmond with his brother-in-law and sister John M. and Mary E. (Morris) Goddin, and it was in that house at 401 W. Marshall Street where their first child, John Stewart Morris (called Stewart) was born on 25 October 1868. Son Stewart was named after John Rives Morris’ company commander and tobacco business boss – Major John Stewart Walker. Major Walker must have been quite important to John Rives Morris to name his first-born son after him.

John Rives and Ann (Vaughan) Morris continued making their home in Richmond living with the Goddins in 1869 and 1870. In 1869, John Rives Morris was working as a clerk and in 1870 he was back at Walker’s factory.[24],[25] The Goddins had several children of their own so when John and Ann found themselves expecting their second child in late 1870, they moved to the corner of 26th and Main Streets [does not say which corner], which was closer to the tobacco stemmery on 17th Street. They would remain there from 1871-1873.[26] The couple’s second child, a son they named Augustus Rives Morris, was probably born there on 2 February 1871, although his death certificate lists his birthplace as Jetersville in Amelia County, Virginia.

The map[27] inset below highlights the intersection in Richmond where the family was living from 1871-1873 as well as Mrs. J.S. Walker’s Tobacco Stemmery [widow of Major John Stewart Walker] on S. 17th Street. Fore those familiar with downtown Richmond today, 26th and [now E.] Main Streets is where Millie’s Diner is located. No building from that time exists on any of the four corners. The building that housed Walker’s factory at 12 S. 17th Street still stands and is now Jackson Pine Apartments.

John Rives Morris found time to join the Masons. He was a member of St. John’s Lodge, Number 36 located in Richmond. His degree dates were 10 September 1867 [entered apprentice], 14 July 1868, [fellow craftsman] and 8 December 1868 [master mason]. He is listed a member for the period 1867-1872. He withdrew on 14 October 1873 but rejoined and was a member from 1874 until his death in 1904. In 1892 he was listed as an honorary member.[28]

It was about this time the little family moved to Creekland Farm in Amelia County located near the village of Jetersville, which was Ann (Vaughan) Morris’ portion of the farm she inherited from her parents. The move was approximately 50 miles. The map insets below highlight both Richmond and Jetersville[29] as well as the location of the Vaughan farm[30] near the village of Jetersville.

A third son was born in 1876 to John and Ann who named him William “Willie” Holland Morris after John Rives Morris’s brother who died in 1863.[31] The family of five is found in the 1880 federal census in Leigh Township in Amelia County, Virginia.[32] A daughter named Ann Vaughan Morris was born in 1886. Youngest son Willie Morris died on 22 January 1897 at the age of 21 – according to my grandmother – from lockjaw resulting from being accidentally shot in the foot while hunting. The 1900 U.S. Census noted that John Rives and Ann (Vaughan) Morris had five children with three living, suggesting that another unnamed child died – probably in infancy and likely during the decade between son Willie and daughter Ann’s births.

As noted in Part 1 – John Rives Morris died in 1904 at the age of 65 when he was gored to death by a bull on the family farm in Jetersville; it being the third time the animal had attacked him.

John Rives Morris and Mental Illness

In Part 1 we considered the family story John Rives Morris was mentally ill and found records to support that conclusion. Whether that means depression or post-traumatic stress disorder or something else – we can’t be sure. While death touched all families during that time, the number of people lost to a young John Rives Morris seems especially long. Perhaps these familial losses, his family’s significant economic reversal of fortune, his year of infantry fighting and living in the midst of one of the most chaotic times in our nation’s history may have just been too much to bear.

Postscript: Another John Rives Morris Family Legend to Research

There is one other notable story about John Rives Morris that has passed down through our family. I was reminded of it while having lunch recently with my cousin Whit Morris. Supposedly, John Rives Morris had a tobacco shipment confiscated at sea by the French government and lost a bunch of money. If this story is true, it seems like it would have occurred during the Civil War when Union naval forces attempted to enforce a blockade to prevent the south from getting supplies or exporting anything that would help the south’s economy. I have always thought the story made little sense as it was the Union forces enforcing a blockade. I learned recently; however, that the French government had representatives in Richmond and Washington trying to secure a sizable tobacco shipment or shipments that had been sold to France prior to hostilities breaking out. So, John Rives Morris was in the right place, in the right industry, and at the right time to have attempted to get a ship through the blockade or to have fallen victim to the French plot to remove tobacco from Richmond. The search continues.

[1] He is listed as John A. R. Morris in the 1850 U.S. Census as well as in 1852 when his name appeared in a newspaper list of those for whom letters were at the post office (Richmond Dispatch, 17 April 1852, p. 1). By 1860, he appears to have dropped use of the A, which is presumed to be for Augustus given that he named a son Augustus Rives Morris. I have conducted an extensive search, can find no evidence of any connection to any Rives family. I am of the opinion that John’s father, James Morris, chose ‘Augustus Rives’ to honor a Virginia politician. William Cabell Rives (1793-1868) represented Nelson and then Albemarle Counties, serving in the Virginia House of Delegates and both the U.S. House and Senate. He was a member of the Democrat Party for much of his career but left to join the Whig Party during the late 1830s. John’s father, James Morris and his grandfather John Morris of Buckingham County were also Whigs. This will be the subject of a future blog post. Since he dropped the “A” so will I and unless it’s a records cite I’ll refer to him as John Rives Morris.

[2] “Document 32 – Report of the Committee on Privileges and Elections, 1840-41 Session,” Journal of the Virginia House of Delegates, (Richmond, VA, printed by Samuel Sheppard, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1840), pp. 99-101.

[3] Elizabeth S. Gills middle name may have been Smith after her maternal grandmother Elizabeth Smith (c.1802-1848) who married John Atkinson. Their daughter Mary A. D. Atkinson married Miles A. Gills.

[4] “Document 32 – Report of the Committee on Privileges and Elections, 1840-41 Session,” Journal of the Virginia House of Delegates, (Richmond, VA, printed by Samuel Sheppard, Printer of the Commonwealth, 1840), pp. 99-101.

[5] Auditor of Public Accounts Personal Property Tax Records, Prince Edward County, VA, 1832-37, Reel 283; 1838-1850, Reel 284, Library of Virginia

[6] Prince Edward County, Virginia Deed Book 23, p. 460, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[7] Amelia County, Virginia Chancery Causes 1892-016, American Memory, Chancery Cause Index, Library of Virginia www.lva.virginia.gov

[8] Prince Edward County, VA Chancery Suit, 1844-030, American Memory, Chancery Cause Index, Library of Virginia website www. www.lva.virginia.gov

[9] City of Richmond, Virginia Deed Book 59, Page 99, Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[10] Ancestry.com; 1850 U.S. Federal Census, City of Richmond, VA; Roll M432_951: Page 378B; Image 288; Dwelling 614, Family 714

[11] Ancestry.com; U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA

[12] Ancestry.com. U.S., Find A Grave Index, 1600s-Current [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2012.

[13] Richmond Dispatch (Richmond, VA), 4 August 1853, p. 2

[14] Ancestry.com; Virginia, Select Marriages, 1785-1940 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA

[15] The last record found concerning John J. Morris was dated March 1857, when he was a plaintiff along with Richard Field, John J. Merritt and Daniel Karr, merchants and partners trading under the name Field, Merritt & Company. The men were suing Levi Carpenter for $21,000 and the notice was to advise the defendant, who was living outside of Virginia, to appear and protect his rights. Richmond Enquirer (Richmond, VA), 3 March 1857, p. 3)

[16] 1860 Richmond City Directory, (Film 229/229A), Library of Virginia, Richmond, VA

[17] Louis H. Manarin. Richmond Volunteers, The Volunteer Companies of the City of Richmond and Henrico County, Virginia 1861 – 1865, Official Publication No. 26, Richmond Civil War Centennial Committee, (Richmond, VA, Westover Press, Richmond, 1969), pp. 203-10; pp. 214-15

[18] Southern Historical Society Papers, Volume XXXV. (Reprinted by Broadfoot Publishing Company, Morningside Bookshop, 1991), p. 128; accessed through http://whatcolorisbutternut.blogspot.com/p/maj-john-stewart-walker.html. One of Major Walker’s descendants has kindly posted transcripts of numerous letters written by him during the War that provide a lot of detail as to what life was like for Company B soldiers during 1861-1862.

[19] Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia” database with images Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/publication/42/civil-war-service-records-cmsr-confederate-virginia: accessed April 22, 2022)

[20] Richmond Whig, 3 March 1863, p. 3

[21] Virginia, Select Marriages, 1785-1940, Ancestry.com, 2014, Provo, UT, USA

[22] Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia, https://www.fold3.com/image/10751492?xid=1945

[23] “Compiled Service Records of Confederate Soldiers Who Served in Organizations from the State of Virginia” database with images Fold3 (https://www.fold3.com/publication/42/civil-war-service-records-cmsr-confederate-virginia: accessed April 22, 2022)

[24] Richmond, Virginia City Directory, 1869

[25] Richmond, Virginia City Directory, 1870

[26] Richmond, Virginia City Directories, 1871, 1873

[27] Beers, F. W. (1877) Illustrated atlas of the city of Richmond, Va. [Richmond, Va.: F. W. Beers] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2005630891/.

[28]Letter dated 12 July 1993 from Mrs. Marie M. Barnett, Librarian, Grand Lodge of Virginia Library and Museum to P. Steven Craig (in possession of compiler).

[29] Waddell, J. H. & Maury, M. F. (1871) Map of Virginia. Richmond, VA: N. V. Randolph. [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2007627314/.

[30] Henderson, D. E., Campbell, A. H., Gilmer, J. F., Minis, L. P., Confederate States of America. Army. Department Of Northern Virginia. Chief Engineer’s Office & Virginia Historical Society. Map of Amelia Co., Virginia. [Virginia: s.n., 186-?] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2012591111/.

[31] John Rives Morris’ brother William Holland Morris was named for a maternal uncle William Holland (1792-1850).

[32] 1880 U.S. Federal Census, Place: Leigh, Amelia, Virginia; Roll: T9_1353; Family History Film: 1255353; Page: 106.4000; Enumeration District: 5; http://search.ancestry.com/cgi-bin/sse.dll?db=1880usfedcen&h=18559846&ti=0&indiv=try&gss=pt

So many thoughts…as your posts have indicated, it would seem that lawsuits were a recreational activity in the early Republic…but also, gored to death by a bull on the third try? Would’ve been summer sausage after the second, for sure!

LikeLike

Lawyers! I have to say that seems like an unpleasant way to die! But I have another blog post in draft about another 2x great grandfather whose death was probably worse. Stay tuned!

LikeLike